Macuxi

- Self-denomination

- Pemon

- Where they are How many

- RR 37250 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Guiana 9500 (Guiana, 2001)

- Venezuela 89 (XIV Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Viviendas, 2011)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

Inhabitants of a border region, the Macuxi have been facing adverse situations since at least the 18th century due to the non-indigenous occupation of the region, initially involving mission villages and forced migrations, later the advance of extraction fronts and farming, and more recently the arrival of prospectors and the proliferation of illegal land sellers in their territory. They have fought for decades, along with other peoples from the region, in one of the biggest impasses in terms of the materialization of indigenous rights in contemporary Brazil, for the ratification of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, which occurred in 2005, and then for the eviction of non-indigenous occupants, finally resolved after the trial conducted by Brazilian Supreme Court in 2009, which confirmed the ratification and the eviction of non-indigenous occupants.

Direct contact

Visite the '''Conselho Indigena de Roraima - CIR (Indigenous Council of Roraima)''' website

Identification and location

The Macuxi, a people speaking a Carib language, inhabit the Guianas region between the headwaters of the Branco and Rupununi rivers, a territory currently divided between Brazil and Guiana. The Macuxi designation contrasts with those of the neighbouring peoples – the Taurepang, Arekuna and Kamarakoto – also speakers of Carib languages and very close socially and culturally to the Macuxi. Taken as a whole, they form a wide ethnic grouping, the Pemon, a term which in turn contrasts with Kapon, a designation that encompasses the Arakaio – known in the Brazilian area by the name Ingarikó – and the Patamona, their northern and north-eastern neighbours respectively. Overall these ethnic designations and their various levels of contrast form a system of identities that singularizes these groups among the Guianese peoples in the circum-Roraima region.

The Macuxi population is currently estimated at around 19,000 people in Brazil and around half this number in neighbouring Guiana, occupying savannah and mountain areas in the far north of Roraima state and the north of the Guianese district of Rupununi.

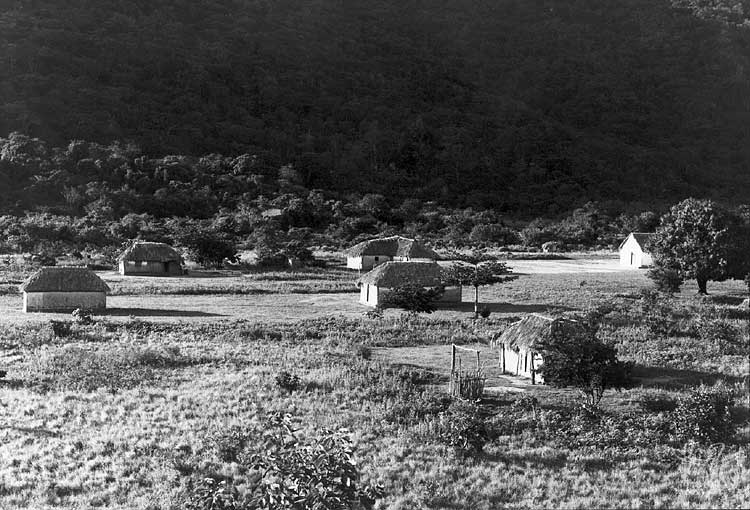

The Macuxi territory extends across two ecologically distinct areas: to the south, the savannahs; to the north, an area dominated by mountain uplands with denser forest, resulting in a slightly different form of exploration to the use made by the Indians of the lowland areas. The territory’s size can be estimated at around 30,000 to 40,000 km2.

The Macuxi population is spatially distributed into various villages and small isolated habitations. It is estimated that today 140 Macuxi villages exist in Brazil, but no precise information exists on their number. For the Guianese area, the estimate is that around 50 villages are located in the Maú(Ireng)-Rupununi interfluvial region.

Notably, this spatial distribution of the Macuxi has remained unaltered over a continuous stretch of lands since at least the era of the first available historiographic records for the Branco river valley region in the 18th century.

The Macuxi territory in Brazil is today cut into three large territorial blocks: the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory (IT) and the São Marcos IT, which together contain the majority of the population, and eight small areas that surround isolated villages in the far northwest of Macuxi territory, in the valleys of the Uraricoera, Amajari and Cauamé rivers.

The most populous area is the Raposa Serra do Sol IT, in the central and largest portion of their territory. This area covers 1,678,800 ha and is inhabited by a global population estimated at 10,000 inhabitants distributed in 85 villages, the large majority of which are Pemon.

The ethnic borders in the region are fairly blurred due to the residential arrangements between cognatic kingroups formed by men from different origins, especially in villages in the zones where ethnic groups intersect. These contain groupings composed by extended families with mixtures of Macuxi and Ingaricó, Macuxi and Patamona, Macuxi and Wapichana, and so on.

The São Marcos IT is contiguous to the Raposa Serra do Sol IT, covering an area of 654,110 ha, home to 24 Macuxi villages and a total population estimated by FUNAI in 1996 of 1,934 Indians, most of them Macuxi.

Contact history

Mission villages

The Portuguese colonial occupation of the Branco river valley dates from the mid 18th century. This colonization was primarily strategic-military in kind. In this region, bordering the Spanish and Dutch territorial possessions in the Guianas, the Portuguese looked to prevent potential attempts to invade their territories in the Amazonian valley. In 1775 they built the Fort of São Joaquim at the confluence of the Uraricoera and Tacutu rivers, headwaters of the Branco, providing access to the basins of the Orinoco and Essequibo rivers.

The strategy used by the Portuguese to ensure their territorial control of the valley was based on using the fort’s troops to settle the Indians in mission villages. To this end, the Portuguese military differentiated the indigenous population into Principaes and their Nations, seeking to convince the former through weapons and gifts of the advantages involved in bringing the people of their respective Nations to form villages.

The information available on contact with the Macuxi during this period is sparse and fragmentary. Surprisingly, the Macuxi appear in small numbers among the different indigenous groups settled at the time: there are accounts of only two Macuxi Principaes: Ananahy in 1784 and Paraujamari in 1788, who also settled in mission villages, bringing small groups with them. However, they did not stay for any length of time in the villages. Soon after these reports, in 1790, Parauijamari would be accused of leading a large rebellion, when most of the settled Indians fled and the remainder were sent to other Portuguese village settlements on the Negro river.

This revolt put an end to the official policy of settling the Indians and no new attempts to colonize the region would be undertaken in the 18th century. However there is considerable evidence that the expeditions for forced recruitment of the indigenous population remained active, motivated by other interests that became established in the region, with a heavy impact on Macuxi demography and territoriality.

Extractivism

A new phase of contact, which would more drastically affect the Macuxi population as a whole, began in the 19th century with the expansion of rubber collecting in Amazonia and, especially, the extraction of caucho and balata rubber in the forests of the lower Branco river. The recruiting of Indians was primarily concentrated in the Negro river area, though ‘descimentos,’ or slave raids, also took place in the valley of the Branco river, where they were used as a labour force in the extraction process.

These private enterprises set the tone for interethnic relations during the period. Although the imperial government demonstrated a continual concern to implement an official indigenist policy in this border zone, the available administrative records reveal its considerable weakness in this area. However in the final decades of the 19th century, in particular after inauguration of the Republic, which conferred greater autonomy to the local government, with the peak of the rubber cycle approaching, the regional population began to be considered necessary collaborators for regional colonization: as the centre of the trade network and the means of communication with the interior, the regatões [traders who exchanged manufactured goods for the extracted products directly with the indigenous and non-indigenous population in the region] held sway there.

Cattle ranching

There seems to be a close connection between extractivism on the lower Branco river and the cattle ranching that became consolidated on the upper course of this river: the extractivist capital would finance cattle farming. At the same time, the initial wave of cattle ranching in the plains of the upper Branco river stimulated the recruitment of Indians as a workforce in the region as a whole. This work was not limited to extraction itself, but included all the correlated activities, in particular navigation of the river. The river merchants and any other entrepreneurs in the area had almost unlimited freedom to penalize the Indians and force them to work. There was no case of anyone being punished for the slavery to which in practice they subjected the Indians.

As a correlate to this forced work, this historical moment was also marked by an equally forced migration, since the exodus of the indigenous population from the upper Branco river arose much more from their expulsion from the land being taken over by cattle ranching than the compulsory relocation of the workforce.

At the turn of the 20th century, the structure for recruiting the indigenous workforce that had been set up over the previous decades persisted, although entering decline. Abandoned villages and flights provoked by the arrival of whites ere not only recorded by the chroniclers of the Branco river, but were also recorded by the Macuxi and remain in their memory today, marked as a dramatic moment in the diverse narratives recounting their political history.

Indigenous organizations

Political leadership among the Macuxi – traditionally merely a position of prominence assumed by an individual within the alliance structure formed by a local group – changed abruptly with the violence of the intensification of the contact with the non-indigenous regional population in the first years of the 20th century, playing a catalytic role in the demands made by the regional population and the indigenist agents (missionaries or public officers) on the indigenous population, dispersed into small local groups.

In the 1970s, a period marked by the intensification and expansion of contact, some of the political leaders from local Macuxi groups came to the fore by performing key functions as intermediaries in the process of establishing communications between the indigenous population living in the villages and the agents of national society.

Mediating with these local chiefs, the indigenist agencies were transformed into alternative sources of industrialized goods for the Indians, rather than the farmers and prospectors. Due to the distinct position of the official indigenist agents and Catholic missionaries compared to the regional population – located at opposite poles in the dispute over the recognition of indigenous territorial rights – the strategy used by the missionaries, and later by Funai, to extend their influence over the Indians was to undermine the clientelist relations linking the latter to the regional population. Until that time, the industrialized items occasionally supplied by the regional bosses to the Indians were recorded by the former in a list of debts to be repaid when necessary by indigenous labour. In order to undermine this system, the missionaries supplied some of the industrialized items demanded by the Indians, while pressurizing them to settle the debts incurred with their various `bosses.’

This `substitution’ of debts was effected through the promotion of annual meetings with the local indigenous leaders, the so-called `tuxaua (chief) assemblies,’ sponsored by the Diocese of Roraima from 1975 onwards, in which those assembled discussed the conditions and ‘merits’ of each community in terms of accessing the goods provided by the missionaries. It is worth noting that the political leaders present at these meetings came from the villages where the missionaries work was concentrated, that is, in the mountain region: a territorial division conceived in opposition to the savannah and, therefore, further away from the ‘farms’ and settlements.

Projects linked to farming and food distribution were implemented but proved unsuccessful, leading to a series of conflicts, disputes and accusations of favouritism between the different religious leaders, giving rise to the emergence of a new type of indigenous organization, also conceived initially by the missionaries, involving the formation of ‘regional councils:’ that is, supra-village authorities, disconnected from the local communities, bringing together Macuxi, Ingaricó, Taurepang, Wapixana and Yanomami leaders.

During the assembly of tuxauas held in January 1984, seven councils were created in the following regions: Serras, Surumu, Amajari, Serra da Lua, Raposa, Taiano and Catrimani. Their function was to mediate relations outside the indigenous communities, both at the level of relations with the regional non-indigenous society, and in terms of the formulation and management of projects sponsored by different agencies. The most active council was undoubtedly the Serras region, which worked with the locations where severe conflicts were taking place with the regional population, presenting formal denunciations to the government authorities.

One outcome of the regional councils was the creation of a general steering group, based in Boa Vista, a moment which directly lead to the emergence of the Roraima Indigenous Council (CIR). The members of this group are elected by open ballot of the regional council members, following a rotating leadership system.

During this process, other organizations have been setup in the region, combining indigenous groups in favour of ratifying the Raposa Serra do Sol IT as a continuous area [on this topic, see the section The Raposa case], such as the CIR itself (whose current coordinator is Macuxi), the APIR (Association of Indigenous Peoples of Roraima), the OPIR (Organization of Indigenous Teachers of Roraima) and OMIR (Organization of Indigenous Women of Roraima). Other organizations are openly against demarcation of the IT as a continuous area, including SODIUR (Society of United Indians for the Defence of North Roraima), ARIKON (Regional Indigenous Association of the Kinô, Cotingo and Monte Roraima Rivers), ALIDICIR (Alliance for the Development of the Indigenous Communities of Roraima) and AMIGB (Guàkrî de Boa Vista Municipal Indigenous Association).

The Raposa case

The Raposa Serra do Sol IT, identified by Funai in 1993 as a continuous area, was ratified by the President of the Republic in April 2005 with an area of 1.747.460 ha. Currently the principal demands made by the Macuxi (and other peoples inhabiting the territory) is for the clearance of the area and the removal of non-indigenous farms that still remain within its borders.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the area today denominated Raposa Serra do Sol, located in the northeast of Roraima, was at the centre of border disputes between Brazil and Great Britain. The region between the Cotingo river (which traverses Raposa–Serra do Sol) and Rupununi (in Guiana) constituted the so-called ‘Contestado.’ In O Direito do Brasil [Brazil’s Right], Joaquim Nabuco, the country’s representative in the difficult border negotiations, emphasizes that the loyalty of the region’s Tuxaua to Brazil, despite the latter’s weak colonial presence at the time, was fundamental to ensuring the country’s present borders on the Maú and Tacutú rivers. Likewise, Marshall Rondon had already stated the Indians are the ‘walls of the outback,” and that the government’s implementation of positive policies in response to their demands, including the demarcation of their lands, is the best recipe for promoting the tranquillity of the border zones.

It is also worth highlighting, as the historical sources clearly show, that the indigenous occupation of Raposa Serra do Sol precedes colonization by centuries. The first colonists settled in between the malocas, but the Indians were gradually pressurized by new waves of migrations stimulated by official policies of the then Federal Territory and current State of Roraima.

After years of waiting in the part of the Indians and various studies, including proposals for withdrawal of the process, the official identification of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT was concluded in 1993, with the publication in the Official Federal Gazette of the geographic coordinates of the area proposed for demarcation. This also included reference to its ‘continuous area,’ extending from the borders with Guiana and Venezuela (east and north) to the limits with the São Marcos IT (west) and the Tacutú river (south). The identification excluded from this continuous area the area around the Vila de Normandia, converted previously into a municipality, forming an enclave on the border with Guiana.

Following the election of President Fernando Henrique, the government minister Jobim froze demarcations for more than a year while Decree 1775 was discussed and an extended period of time was given for hearing third-parties during the demarcation process. Promulgation of the decree led to more than a hundred contestations against the proposed limits for Raposa Serra do Sol and, at the end of the period in question, the Minister of Justice issued on 20/12/96, a ‘decree’ in which he rejected the contestations and recognized the constitutionality of the anthropological report on which the demarcation proposal was based. But instead of declaring it an Indigenous Territory, he alleged that ‘actual situations,’ created by centres of urban and rural occupation that he considered to be ‘already consolidated,’ required ‘adjustments’ to the proposed limits.

The ‘consolidated urban and rural centres’ cited by the ministerial decree comprised or implied the following: the creation of the Municipality of Uiramutã, which occurred after the official identification of the Indigenous Territory; the presence of another four small towns in the central north of the proposed area; the validity of some land deeds pertaining to the southern part, as well as the presence of rice growers, cattle ranchers and prospectors who had invaded the area in recent years; the free transit of non-Indians on the roads providing access to these localities; and the overlapping of the Monte Roraima National Park – a Federal Conservation Unit – and the demarcated area.

The State of Roraima preferred to ignore the indigenous entitlement to these lands, even after their official identification, and created the Municipalities of Uiramutã and Pacaraima (the latter in the São Marcos IT) as part of a deliberate confrontation with the demarcation proposals. Its initiative challenged the identification of the area made by Funai and ignored the negotiation channels, with Roraima State arguing for the demarcation in ‘islands,’ which recognized Indian rights to land only in the areas immediately surrounding each maloca and would render impossible their physical and cultural reproduction as ensured by the Constitution, while simultaneously producing a situation that would lead to permanent conflict.

The minister failed to implement his decree in the form of a directive with the ‘adjusted’ limits to the area, leaving the problem to be resolved by his successors. Within Funai, implementing the minister’s indications in the form of a new directive proved impossible since it would imply the exclusion of various villages from the area set to be demarcated. As time passed, the prospecting activity declined, the ‘consolidated nucleuses’ emptied and some of the ‘farmers’ made agreements with specific communities and withdrew from the area.

Observing that earlier occupations taken as ‘consolidated’ had dispersed and that new illegal occupations, undertaken subsequent to identification, were starting to threaten the integrity of the Indigenous Territory, Funai once again forwarded the proposal for a ‘continuous area’ to the Minister of Justice, Renan Calheiros. He signed the ministerial directive (No. 820, of 11/12/98), with the proviso that the federal government would subsequently enable solutions to the ‘actual situations’ identified by his predecessor, but left the job without providing them.

The ministerial directive was contested by the State of Roraima at the High Court of Justice, which initially issued an injunction blocking ratification of the area, but not its demarcation. During the period of the injunction, Funai undertook the work of physically demarcating and computerizing the borders, facilitated by the natural and international frontiers followed in the proposal for the ‘continuous area,’ informing the process of presidential ratification. Finally, the High Court of Justice rejected the writ of mandamus solicited by the State, overcoming the last formal obstacle to ratification. This decision was reached during the final stages of President Fernando Henrique’s term of office, but the latter decided not to issue the decree of ratification, leaving the matter pending for the Lula government.

Below we provide a Chronology of official recognition of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT, including the first years of the Lula government.

1917– Government of Amazonas issues State Law No. 941, allocating the areas between the Surumu and Cotingo rivers for occupation and use by the Macuxi and Jaricuna Indians.

1919– Indian Protection Service (SPI) begins physical demarcation of the area, which was being invaded by farmers. However, the work was not completed.

1977– President of the National Indian Foundation (Funai) sets up an Interministerial Work Group (GTI) to identify the limits of the Indigenous Territory; this, though, failed to present a conclusive report on its work.

1979– New GTI is formed. Without using anthropological and historiographic studies, it proposes a provisional demarcation of 1.34 million ha.

1984– Another Interministerial Work Group is set up for the identification and land ownership survey of the area. Five contiguous areas – Xununuetamu, Surumu, Raposa, Maturuca and Serra do Sol – were identified, totalling 1.57 million ha.

1988– Another Interministerial Work Group carries out the land survey without reaching any firm conclusion concerning the area as a whole.

1992/1993– FUNAI decides to restudy the area, forming for the last time yet another Interministerial Work Group.

1993– Official conclusive findings of the Work Groups, are published in the Official Federal Gazette on the 21st May, proposing recognition of the continuous area of 1.67 million ha to the Ministry of Justice.

1996– The President of the Republic, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, signs Decree 1.775 in January, which introduces the principle of contestation in the process of recognizing ITs, allowing contestation by those affected. Forty-six administrative contestations are presented against the Raposa Serra do Sol IT by non-indigenous occupants and by the Roraima state government. The then Minister of Justice, Nelson Jobim, signs Decree 80, rejecting the requests for contestation presented to Funai, but proposing a reduction in size of about 300,000 ha to the area, with exclusion of small towns that formerly served as bases of support for prospecting, roads and farms granted by INCRA, which represented a division of the area into five parts.

1998– Minister of Justice, Renan Calheiros, signs Decree 050/98, revoking Decree 080/96, and Directive 820/98, which declares the Raposa Serra do Sol IT to be under permanent ownership of indigenous peoples.

1999– Roraima State Government petitioned for a writ of mandamus in the High Court of Justice (STJ), with a request to annul Directive 820/98. A temporary injunction to the writ of mandamus is granted to the Roraima government.

2002– STJ rejects request for the Writ of Mandamus 6210/99, petitioned by the Roraima state governor and requesting annulation of Directive 820/98.

2003– The Justice Minister, Márcio Thomaz Bastos, announces, at various moments during the year, that ratification of the IT is imminent.

2004– In March, a judge of the First Federal Court of Roraima suspends demarcation in the consolidated urban and rural centres. In May, the Federal Associate Justice determines the exclusion of the border zone (150 Km), which eliminates the entire Indigenous Territory. In August, both the High Court of Justice (STJ) and the Supreme Federal Court reject requests from the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Attorney General’s Office (AGU) to overturn the decision of the Regional Federal Court (TRF), which is preventing ratification of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT.

2005– On April 13th, the Justice Minister, Márcio Thomaz Bastos, signs Directive No. 534, revoking Directive No. 820/98, which had established the demarcation of the IT and was being questioned by various appeals. The new regulatory act excludes the urban centre of the municipality of Uiramutã, public facilities (such as schools and electricity transmission lines), the 6th Special Army Border Platoon and the federal and state roads located within the area.

2006– The year is marked by a series of actions in the courts through which some farmers look to remain within the Indigenous Territory, delaying the process of compensation payments for fixed assets and the clearance of the area. In April, the Supreme Federal Court requests the request to suspend demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT.

2007– In May, the minister of the Supreme Federal Court (STF), Carlos Britto, orders the cessation, until final judgment, of the clearance of the area occupied by Itikawa Indústria e Comércio, Ivalcir Centenaro, Luiz Afonso Faccio, Nelson Massami Itikawa and Paulo César Quartiero, in response to the writ of mandamus filed by Itikawa and other parties. In June, the Supreme Federal Court unanimously rejects the Writ of Mandamus 25.483-1, enabling resumption of the work of clearance.

Further reading

For more information on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, see the special report produced by ISA

Social organization

The villages in the forest comprise communal houses inhabited by different domestic groups composed by extended families linked through kinship. In the savannah, on the other hand, we generally find scattered houses containing domestic groups whose composition is analogous to the previous: in this sense, the village in the savannah is a dispersed version of the typical communal houses in the forest.

Although the sources from the 19th century refer to the existence of Macuxi villages organized in communal house with a low demographic density, that is, between thirty and seventy people living in each (R. Schomburgk 1922-23; R.H. Schomburgk 1903), today villages are composed of small houses containing extended families and uniting a larger population, estimated between 100 and 200 inhabitants.

The layout of the Macuxi village does not immediately reveal its social morphology. The houses seem to be distributed randomly, though looking more closely it can be observed that, in general, they are arranged in clusters that correspond to kingroups. These form political units whose interaction pervades the village’s social and political life.

The Macuxi village basically consists of one or several kingroups interconnected by marriages. Given the uxorilocal tendency (after marriage, the couple goes to live with the girl’s family) found in the societies of this region, residence and kinship are associated domains, which, in combination, provide the basis for local leadership. Hence the local group is organized around the figure of a leader/father-in-law whose position depends on his political ability in manipulating kinship ties. When the prestige of the leader/father-or-law declines, or he dies, the local group tends to assume other forms or dissolves. Even in the latter case, however, the village persists as a historical-geographic reference point.

Macuxi matrimonial politics tends to favour endogamic unions, or in other words, marrying within the kingroups that compose the village. Nevertheless, a high incidence of marriages can be observed between villages that intensify their relationships, producing regional groupings.

As applies to other Pemon groups, for the Macuxi the relation between brothers-in-law – yakó – is marked by a wide degree of freedom and egalitarianism, while, conversely, the father-in-law/son-in-law relation – pái-to – presumes avoidance, subordination and considerable material obligations on the part of the latter to the former.

In the village, political leadership therefore emerges as an interplay between kingroups in which the accumulation of relations of affinity predominates: that is, the leader is someone who possesses a wider network of affines and, therefore, political allies. Today another crucial factor is the activities of indigenous and indigenist agencies, which allow leaders to gain prestige and material support that confers them greater stability.

Cosmology and shamanism

The Macuxi universe is basically composed of three planes superimposed in space that meet on the horizon. The terrestrial surface where we live is the intermediary plane: below this surface, there is a subterranean plane, inhabited by the Wanabaricon, beings similar to humans but small in size, who plant swiddens, hunt, fish and build villages.

The sky that we see from the terrestrial surface is the base of the upper plane, Kapragon, peopled by a variety of beings, including the celestial bodies and allied animals, who also live like humans, hunting, fishing and cultivating. The Macuxi have no kind of relationship with the beings inhabiting these other planes of the universe, which also never interfere in their lives.

The intermediary plane, for its part, is not the exclusive domain of humans and animals, but is also inhabited by another two classes of beings, Omá:kon and Makoi. The distinction between these two classes seems to be based on the place inhabited by each of them. Thus the Omá:kon category preferentially inhabits the mountains, especially the rocky and more arid areas of the ranges, as well as the forests. Although their appearance varies considerably, they are markedly wild or anti-social: they have long nails and hair and speak incoherently. They usually appear in the form of game animals, though they are the hunters of humans.

The Makoi beings, on the other hand, are predominantly aquatic, inhabiting waterfalls and deep pools. In general, they appear in a variety of forms of aquatic snakes. They are considered the most dangerous beings for humans, attracting them to their domain and devouring them.

When the Omá:kon and Makoi imprison a human soul (Stekaton), the victim sickens and eventually dies. Only the shamans (Piatzán) can confront predation by the Omá:kon and Makoi, since they possess the faculty of seeing them and have supernatural weapons capable of neutralizing them. In fact, the therapeutic action undertaken by shamans – since illnesses are evidence of attacks on the soul caused by these two classes of beings – basically involves rescuing the captured soul prevented from returning to the body, and songs performed during a shamanic session that describe the events involved in this action.

Cosmogony

The Kapon say that they are all Tomba – or Domba, kin – just as the Pemon identify all of themselves as Yomba, kin, similars. The two groups consider themselves to be related, common descendents of mythic heroes (brothers): Macunaíma and Enxikirang. As told by an oral tradition shared by all these groups, these mythic heroes, sons of the sun – Wei – forged the current shape of the world during an ancient era – Piatai Datai.

In various narrative versions – Pandon – these peoples tell that Macunaíma perceived bits of maize and pieces of unknown fruits between the teeth of a agouti, sleeping with its mouth open. So he decided to follow the small animals and came across the Wazacá tree – the tree of life – in whose branches grew all the types of cultivated and wild plants eaten by the Indians. Macunaíma therefore chopped down the trunk – Piai – of the Wazacá tree, which leaned towards the northeast. Hence all the edible plants found today fell in this direction, especially in the areas covered in forest.

From the trunk of the Wazacá tree spouted a torrent of water, which caused a great flood during this primordial period. According to the myth, this trunk remains still: this is Mount Roraima, whence flow the rivers that pass through the traditional territory of these peoples. The myth thus tells of the origin of agriculture, which marks humanity, as well as ethnic differentiation, also expressed in the geographic localizations.

Productive activities

The climate in the region inhabited by the Macuxi is marked by heavy rainfall and two well-defined seasons: winter, with rains concentrated from May to September, and summer with a prolonged dry season from November to March. Hence these seasonal alterations are fairly significant for the region’s wildlife and plants.

During the winter months, the torrential rains swells the beds rivers and creeks, eventually flooding many of the low-lying areas with the exception of some of the higher points on the floodplains, which form small islands.

For the Macuxi, these islands, along with mountain slopes, are the preferred sites for cultivating manioc and maize.

The population, which had concentrated in the villages during the dry season, disperses into small groups during the rainy season, which begin to live in isolation with the food produced in the family swiddens and collected in the forests covering the mountain uplands.

For a brief period of transition between the seasons, the vegetation previously submersed in the fields flourishes and the animals leave their refuges on the floodplain islands and in the uplands to use their more extensive habitat. The Indians, who had been living dispersed in small domestic groups, reunite in extended kingroups in the villages, undertaking collective hunting and fishing expeditions, along with various other economic activities pursued in the dry season.

In the summer months, the savannah plants wither and dry, and green vegetation becomes limited to the lower areas closest to the rivers and creeks, most of which are intermittent and dry completely at the height of the dry season. The Indians return to the pools found in the riverbeds and the lakes that still hold water, looking to surprise the game animals looking for a watering hole at the same locations, as well as devoting much of their time to fishing, which becomes the main activity during this period.

In the dry season, the Indians also devote time to building and repairing houses and, as correlated activities, extracting the timber and clay used in the house frameworks and side walls, as well as collecting palm leaves for the house thatch, the most frequent being burity palm. They also collect a wide variety of plant fibres used to make artefacts.

A network of paths and trails through the savannah and forests also becomes clearly visible during the dry season, linking the locales for collecting, hunting and fishing, and the different villages. These paths receive intensive use by the Indians, who take advantage of them to visit relatives, strengthening the social relations and political alliances between the kingroups during festivals and ritual celebrations.

The Macuxi practice slash-burn agriculture, basically cultivating manioc, maize, yam, sweet potato, banana, watermelons, pineapple and a smaller amount of other crops that vary from village to village. The tasks of felling the trees, burning the swidden area and planting are carried out by men. After this work, women are primarily responsible for keeping the swidden clear of weeds and harvesting the crops, as well as cooking the foods. Men devote themselves to hunting, fishing and collecting wild fruits, undertaking expeditions far from the village.

Today the Macuxi communities established in each village collectively owns small herds of cattle, obtained through projects launched by the Diocese of Roraima, Funai and the Roraima state government. Breeding cattle, kept in pens and enclosures, as well the poultry and swine kept by individual families, is today considered indispensable given the increasing scarcity of wild game.

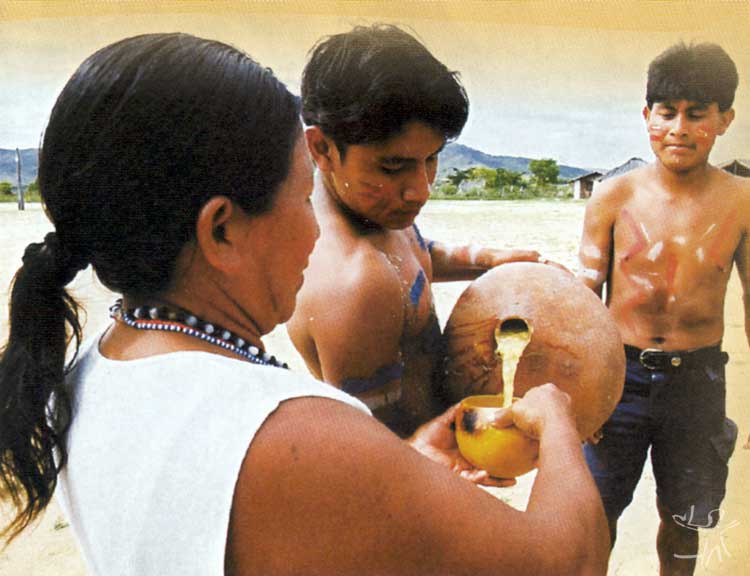

This collective ownership of cattle does not seem to have affected the traditional organization of production by domestic groups. The herd is entrusted to a cowboy, who calls on the community when larger-scale work is required. This is undertaken with a plentiful supply of caxiri and pajuaru – drinks made from fermented manioc – as in other situations involving mutual help between kingroups.

Sources of information

- ALMEIDA, Tânia Mara Campos de. O levantamento e a vistoria das ocupações de não índio: o caso da Terra Indígena Barata/Livramento (RR). In: GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Org.). Demarcando terras indígenas II : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 2002. p.151-68.

- AMÓDIO, Emanuele. Murei : saber mítico y bancos chamánicos entre los Makuxi de Brasil. In: AMÓDIO, Emanuele; JUNCOSA, José E (Comps.). Los espiritus aliados : chamanismo y curación en los pueblos indios de Sudamerica. Quito : Abya-Yala ; Roma : MLAL, 1991. p. 155-88. (Colección 500 Años, 31)

- ANDRELLO, Geraldo L. Relatório sobre a Terra Indígena São Marcos : histórico e situação geral. São Paulo : Eletronorte, 1998. 120 p.

- CENTRO DE INFORMAÇÃO DIOCESE DE RORAIMA. Índios de Roraima : Makuxi, Taurepang, Ingarikó, Wapixana. Boa Vista : Diocese de Roraima, 1989. 106 p.

- CONSELHO INDÍGENA DE RORAIMA. Raposa Serra do Sol : os índios no futuro de Roraima. Boa Vista : CIR, 1993. 40 p.

- --------; COMISSÃO PRÓ-ÍNDIO DE SÃO PAULO. Parecer sobre o relatório de impacto ambiental da hidroelétrica de Cotingo. São Paulo : CPI, 1994. 37 p.

- DINIZ, Edson Soares. Os índios Makuxi do Roraima : sua instalação na sociedade nacional. Marília : FFCLM, 1972. 191 p. (Teses, 9)

- --------. O perfil de uma situação interétnica : os Makuxi e os regionais de Roraima. Boletim do MPEG: Antropologia, n.31, 37 p., abr. 1966.

- ELETRONORTE. Interligação elétrica Venezuela-Brasil : processo de negociação com as comunidades indígenas das TIs São Marcos e Ponta da Serra. s.l. : Eletronorte, 1997. 69 p.

- FARAGE, Nádia. As muralhas dos sertões : os povos indígenas no Rio Branco e a colonização. Campinas : Unicamp, 1986. 469 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- GOUVÊA, Ana Cristina de Souza Lima. O parâmetro da ergatividade e a língua karibe macuxi. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1994. 175 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- GRUPIONI, Luis Donisete Benzi. O ponto de vista dos professores indígenas : entrevistas com Joaquim Mana Kaxinawa, Fausto Mandulao Macuxi e Francisca Novantino Pareci. Em Aberto, Brasília : Inep/MEC, v. 20, n. 76, p. 154-76, fev. 2003.

- KOMPF, J. et al. Linked loci in chromosome 1 (FXIIIB, HF, PEPC) and their variability in Brazilian indians. American Journal of Human Biology, New York : s.ed., v. 4, n. 5, p. 573-7, 1992.

- MARTINS, Leda Leitão. Dominando la malaria : un nuevo modelo de salud para poblaciones indígenas en Brasil. Desarrollo de Base, Arlington : Fundación Interamericana, v. 22, n. 1, p. 11-6, 1999.

- MELO, Maria Auxiliadora de Souza. Metamorfoses do saber Macuxi/Wapichana : memórias e identidade. Manaus : UFAM, 2000. 170 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MEYER, Alcuino. Pauxiána : pequeno ensaio sobre a tribo Pauxiána e sua língua, comparada com a língua Macuxí. Rio de Janeiro : Arquivo Nacional, 1956. 50 p.

- MONTANHA, Vilela. Os bravos de Oixi : índios em luta pela vida. Uma estória baseada em fatos reais. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1994. 232 p.

- MYERS, Iris. The Makushi of the Guiana - Brazilian frontier in 1994 : a study of culture contact. Antropológica, Caracas : Fundación La Salle, n. 80, 98 p., 1993.

- OLIVEIRA JÚNIOR, Geraldo Barbosa de. Os Macuxi : desenvolvimento e políticas públicas em Roraima. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1998. 138 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PENGLASE, Ben. Brazil : violence against the Macuxi and Wapixana indians in Raposa Serra do Sol and Northern Roraima from 1988 to 1994. New York : Human Rights Watch/Americas, 1994. 30 p.

- PIRA, Vicente; AMODIO, Emanuele. Makuxi Maimu : guias para a aprendizagem e dicionário da língua Makuxi. Boa Vista : Centro de Documentação de Culturas Indígenas de Roraima, 1983. 184 p.

- RAPOSO, Gabriel Viriato. Ritorno alla maloca : autobiografia di un indio Makuxi. Parma : I.S.M.E. ; Milão : P.I.M.E. ; Torino : Missioni Consolata, 1972. 126 p.

- REPETTO, Maxim. Roteiro de uma etnografia colaborativa : as organizações indígenas e a construção de uma educação diferenciada em Roraima, Brasil. Brasília : UnB, 2002. 297 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- SALDANHA, Paula; WERNECK, Roberto. Expedições, terras e povos do Brasil : Yanomamis e outros povos indígenas da Amazônia. Rio de Janeiro : Edições del Prado, 1999. 95 p.

- SANTILLI, Paulo José Brando. Fronteiras da República : história e política entre os Macuxi no vale do rio Branco. São Paulo : USP-NHII ; Fapesp, 1994. 119 p.

- --------. Laudo assistencial-técnico pericial antropológico : Ação de Interdito Proibitório 011/92 - AD - Processo nº 92.0001637-5. s.l. : s.ed., 1995. 25 p. (AI: Cajueiro)

- --------. Laudo Pericial Antropológico atinente ao processo nº 92.1634-0 em tramite na Justiça Federal de 1ª Instância, Secção Judiciária de Roraima. s.l. : s.ed., 1995. 44 p. (Fazenda Guanabara)

- --------. Laudo Pericial Antropológico originado da Carta Precatória nº 93.00096-9 componente do processo nº 91.13363-9. s.l. : s.ed., 1994. 118 p. (AI: Raposa-Serra do Sol)

- --------. Os Macuxi : historia e politica no século XX. Campinas : Unicamp, 1989. 162 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Mito e história Makuxi. Terra Indígena, Araraquara : Centro de Estudos Indígenas, v. 9, n. 63, p. 19-29, abr./jun. 1992.

- --------. Ocupação territorial Macuxi : aspectos históricos e políticos. In: BARBOSA, Reinaldo Imbrozio; FERREIRA, Efrem Jorge Gondim; CASTELLON, Eloy Guillermo (Eds.). Homem, ambiente e ecologia no estado de Roraima. Manaus : Inpa, 1997. p. 49-64.

- --------. Pemongon Pata : território Macuxi, rotas de conflito. São Paulo : Unesp, 2001. 226 p. (Originalmente Tese de Doutorado, USP 1997)

- --------. Trabalho escravo e brancos canibais : uma narrativa histórica Macuxi. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp, 2002. p. 487-506.

- --------. Usos da terra, fusos da lei : o caso Makuxi. In: NOVAES, Regina Reyes; LIMA, Roberto Kant de, orgs. Antropologia e direitos humanos. Niterói : EdUFF, 2001. p. 81-136.

- SILVA, Orlando Sampaio. Notas sobre algunos pueblos indígenas de la frontera amazónica de Brasil en otros paises de sudamerica. In: JORNA, P.; MALAVER, L.; OOSTRA, M. (Coords.). Etnohistoria del Amazonas. Quito : Abya-Yala ; Roma : MLAL, 1991. p. 117-32. (Colección 500 Años, 36)

- SIMONIAN, Lígia Terezinha Lopes. Direitos e controle territorial em áreas indígenas amazônidas : São Marcos (RR), Urueu-Wau-Wau (RO) e Mãe Maria (PA). In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p.65-82.

- --------. Mulheres indígenas Roraimenses : organização política, impasses e perspectivas. In: SIMONIAN, Lígia Terezinha Lopes. Mulheres da Amazônia brasileira : entre o trabalho e a cultura. Belém : UFPA/Naea, 2001. p.151-204.

- Ou vai ou racha, 20 anos de luta. Dir.: Mari Correa; Vincent Carelli. Vídeo Cor, 31 min., 1998. Prod.: CTI