Guajajara

- Self-denomination

- Guajajara, Tenetehara

- Where they are How many

- MA 28858 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

The Guajajara are one of Brazil's most numerous indigenous peoples. They live in 11 Indigenous Lands at the eastern margin of the Amazon region, all of them located in Maranhão State. Their history of more than 380 years of contacts is marked by both approaches to whites and total refusals, submissions, revolts, and great tragedies. The 1901 revolt against Capuchin missionaries provoked the last "war against the Indians" in Brazilian history.

Name

Besides calling themselves Guajajara, there is another more comprehensive proper name, Tenetehára, including also the Tembé Indians. Guajajara means "owner of the feathered head ornament" and Tenetehára, "we are the real human beings". Sometimes the Guajajara translate Tenetehára as "Indian", excluding from this category Jê groups as the Canelas, who are called àwà ("wilds, barbarians"). There is no certainty about the origins of the name Guajajara, but probably the Tupinambá gave it to the Tenetehára. Both among the Indians themselves and in the scientific literature, the name Guajajara nowadays is more used than Tenetehára.

Language

The Guajajara language belongs to the Tupi-Guarani family, and their most closely related languages are Asurini (of Tocantins), Avá (Canoeiro), Parakanã, Suruí (of Pará), Tapirapé and Tembé, which is very similar to it. The Guajajara call their language ze'egete ("the good speech"). Linguists subdivided it in four dialects being mutually intelligible without further complications. In the villages, Guajajara is spoken as the first language, while Portuguese, which is understood by the majority, has a lingua franca function. The socio-linguistic situation of the Guajajara who live in towns and cities is unknown.

Location

All 11 Indigenous Lands inhabited by the Guajajara are located in the centre of Maranhão State, in the regions of the Pindaré, Grajaú, Mearim and Zutiua rivers. They are covered by high Amazon forests and lower cerradão forests, the last being transitional forests between the tropical forests of the Amazon and Central Brazilian savannahs (cerrados). The Guajajara never occupied the adjacent savannah regions, traditionally inhabited by Jê peoples.

Since the late Eighteenth Century and the early Nineteenth Century, they expanded their territory to the Grajaú and Mearim river regions where they settled shortly before the arrival of the whites, disputing hunting areas with various Timbira groups. About 1850, a part of the Tenetehára migrated to the north and formed a group some times later being called Tembé by the regional population.

Their current Indigenous Lands, all of them ratified by presidential decree and registered with the exception of one (the Indigenous Land Krikatí), are the following:

| Indigenous Land | Municipality | Size (hectares) |

| Araribóia | Amarante, Grajaú, Santa Luzia | 413.288 |

| Bacurizinho | Grajaú | 82.432 |

| Cana-Brava | Barra do Corda, Grajaú | 137.329 |

| Caru | Bom Jardim | 172.667 |

| Governador | Amarante | 41.644 |

| Krikatí | Amarante, Montes Altos, Sítio Novo | 146.000 |

| Lagoa Comprida | Barra do Corda | 13.198 |

| Morro Branco | Grajaú | 49 |

| Rio Pindaré | Bom Jardim, Monção | 15.002 |

| Rodeador | Barra do Corda | 2.319 |

| Urucu-Juruá | Grajaú | 12.697 |

The Indigenous Lands Araribóia, Bacurizinho and Cana Brava are occupied by approximately 85% of the Guajajara population. In some of the Indigenous Lands, they are not the only indigenous inhabitants: there are Guajá groups in Araribóia and Caru, Tabajara groups in Governador and Rio Pindaré, and Guarani, Krenyê and Kokuiregatejê groups in Rio Pindaré. In two Indigenous Lands the Guajajara are minority: in Governador, where they represent approximately 36% of the inhabitants, and in Krikatí, where there is one community whose members do not speak any more the indigenous language. In the Indigenous Land Geralda/Toco Preto, of the Kokuiregatejê people, formerly registered as being Guajajara land, there lived only one Guajajara man in 2000.

Demography

The precise number of the Guajajara population is unknown, because Funai statistics are incomplete and disregard some villages. According to Funai data, completed by the author of this article, there may have been at least some 13.100 individuals in the Indigenous Lands in 2000. The number of the Guajajara who live in cities like São Luís, Barra do Corda, Grajaú, Imperatriz or Amarante, however, is unknown, neither exist estimations about them.

Based on comparative calculations, Mércio Gomes estimated the population at being some 3.000 at the time of their first contacts with the whites. In 1942, Charles Wagley and Eduardo Galvão supposed it to be about 2.000 individuals. Later on, Gomes calculated 2.500, 3.000 and 4.300 individuals corresponding to the years of 1942, 1953 and 1975. There are no precise numbers about current population growth, which may be between 2,5% and 3,0% per annum. There also lack statistics about current infant and adult mortality rates, which do not seem to be lower than those of the regional population, which are still high.

Neither exist statistics about interethnic marriages nor about their offspring. The most common form of these marriages is not, as could be expected, between white men and indigenous women, but, on the contrary, there are more men than women who migrate to the cities, while the unmarried women represent a kind of "social capital" for their families, because they can attract sons-in-law and, herewith, some male workers for the family's group.

History of contact

The Guajajara have a long and quite unique history of contacts with the whites. The first contact might have occurred in 1615 at the banks of Pindaré River with a French expedition of reconnaissance. Until the mid Eighteenth Century, the Tenetehára were persecuted by Portuguese slave-hunting expeditions in the middle Pindaré course. This situation changed with the establishment of Jesuit missions (1653-1755), which offered some protection from slavery, but gave raise to a system of dependency and serfdom.

After expulsion of the Jesuits from the colony by the crown the Tenetehára succeeded in reconquering some part of their former independence by reducing its contacts with the colonizers. Since the mid Nineteenth Century, they were gradually integrated in regional systems of patronage with all their well-known forms of extreme exploration (for example, as collectors of forest products or as oarsmen). The indigenist politics of that time did not schedule any kind of protection against those abuses. The Guajajara sometimes reacted violently, but generally stayed obedient.

Their greatest revolt, however, was provoked by a Capuchin missionary and colonizing project, starting in 1897 at Alto Alegre in the modern Cana Brava area. In 1901, the chief Cauiré Imana succeeded in uniting a great number of villages to destroy the mission and expel all the whites from the region between the towns of Barra do Corda and Grajaú. Some months later, the Indians were defeated by a militia composed of contingents from the army, the military police (Polícia Militar), individuals from the regional population and Canela warriors and were still persecuted for some years, causing more dead among the Guajajara than among the whites. The Alto Alegre revolt represents one of the most important incidents in the history of this people.

New conflicts arose in the 1960s and 1970s with the uncontrolled expansion of great rural properties in the centre of Maranhão state, pushing many small peasants without land titles into Indigenous Lands. The principal stage of conflict was again Cana Brava, this time with the illegal settlement of São Pedro dos Cacetes, which existed between 1952 and 1995 and which the Guajajara resisted during four decades with nothing but some sporadic help from Federal Government. Other threats arose in the 1980s with the Greater Carajás Programme and the avidity of small regional logger companies.

The contacts with other indigenous ethnic groups - Guajá, Urubu-Ka'apor and some Timbira groups (among these the Canelas) - are traditionally characterized by hostilities. Despite the end of armed conflicts there still exist some interethnic resentments, especially against the Canelas and Guajá.

Economic activities

The principal subsistence activity is agriculture, normally being planted bitter manioc, sweet cassava, maize, rice, squash, watermelons, beans, broad beans, yam, cará (another tubercle similar to yam), sesame and peanuts. In the dry season, from May to November, are undertaken the cutting down of smaller woods (broca), felling of trees (derrubada), clearance of ground by fire (queimada) and removing of smaller rests of woods and roots (coivara), while from November to February the Guajajara plant and weed.

The areas cultivated per residential unit generally are small: currently, they vary between 1,25 hectare and 3,55 hectare per household, or between 0,25 hectare and 0,71 hectare per individual, correspondingly. These variations depend principally upon the involvement of communities and individuals in commercialising agricultural products.

Some villages have great common planting areas prepared by community projects for cultivating rice and various kinds of fruits for commercialising. In many clearances can be found a plant not yet identified called canapu by the Guajajara. It is a kind of shrub some 60 centimetres high yielding small yellowish fruits, which are mellow and full of small seeds, being similar to grape. It is interesting to observe that this plant has no practical function for contemporary Guajajara, but they mention it as being their food in mythical times before Maíra, their Creator, taught them to cultivate. These mythical narrations explain why the plant is not uprooted during weeding.

Fishing is more practised by riverine villages. The Guajajara use to fish some 36 different species, being the cará (Geophagus brasiliensis), the cascudo (Loricaridii fam.), the lampreia (Petromyzon fluviatilis), the mandi (Pimelodidii fam.), the pacu (Metynnis Cope), the piau (Leporinus Spix and Schizodon Agass, Caracidii fam.) and the traíra (Hoplias malabaricus) the most common. In recent years, however, small dams were constructed by several community development projects near some villages located far away from rivers. For the inhabitants of these villages the dams make it possible for them to fish both for subsistence and for commerce.

During the last decades hunting became an ever less producing activity because of competition with the whites for hunting areas and the spatial limitations of Indigenous Lands. The Guajajara traditionally hunt more than 56 species, being the most common some peccary species (Tayassuidii fam.), the cutia (Disyprocta Ill.; a rodent), the jacamim (Psophidii fam.; various kinds of birds), the jacu (Cracidii fam.; various kinds of birds) and various kinds of monkeys and armadillos. In some parts of the Guajajara lands hunting became more productive again since the 1990s after starting with more effective controls of the Indigenous Lands' limits by the Indians themselves.

Collecting is still practised by almost all Guajajara. Collecting activities, however, become ever more substituted by fruit-tree cultivation in the villages and planting areas. The Guajajara nowadays plant some 30 kinds of fruit-trees and palm trees. The only forest product still being collected in larger quantities for commercial ends is honey.

The economic relations with the whites are based on both material and monetary exchanges. The most common sources of revenue are commercialising agricultural products, selling handicraft, temporary services for peasants and more permanent employments by Funai. Another money resource is selling marijuana, which is traditionally planted by the Guajajara. Marijuana was introduced by African slaves in the Eighteenth Century, and his consumption still is an integral part of this indigenous culture, but his commercialisation causes very serious and violent conflicts with the Federal and Military Police (Polícia Federal and Polícia Militar).

A very serious problem is predatory commercialisation of Indigenous Lands' natural resources caused by giving concessions to loggers and hunters with the aim to obtain small profits in the short run for buying, for example, remedies not provided by insufficient government services.

Social and political organization

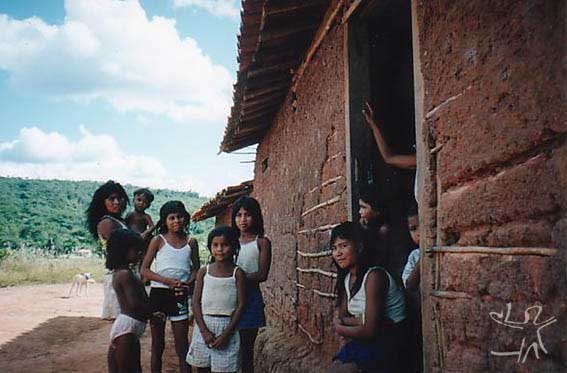

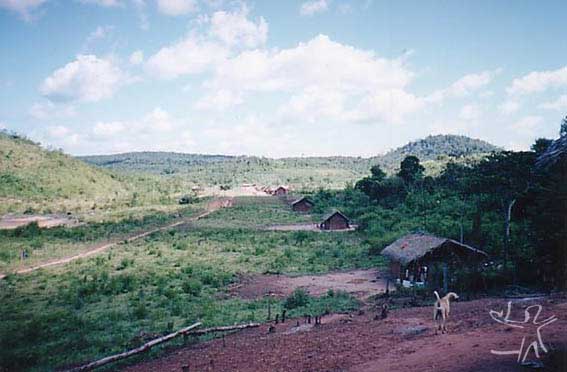

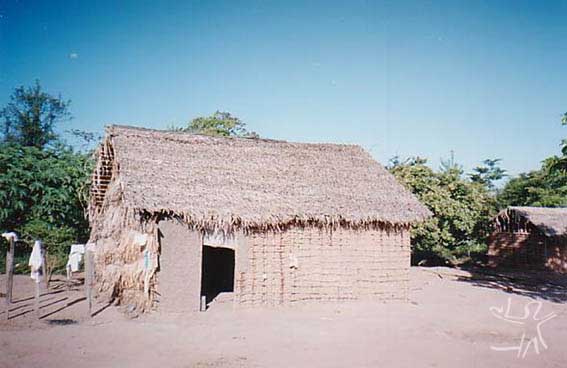

Nowadays, the villages do not have typical forms any more: they are extended (along roads or paths), circular or quadrangular. They are preferentially located on riverbanks or near small lakes (lagoas) in the forests, if there is no watercourse. The proximity of a road can be another attractive factor as, for example, for selling handicraft.

The villages, in former times being very small and having only temporary existence, nowadays are permanent and rarely dislocated. They can be composed by only one family, but in some cases can have as many as 400 or more inhabitants. The houses are built in regional peasant style and are generally occupied by nuclear families. The villages use to maintain their independence and rarely form regional coalitions, but there are various kinds of kinship, marriage and ritual relations between communities.

The kinship system and the forms of marriage stand out by their flexibility in establishing relationships and taking advantage of them. The most important unit is the extended family, which is composed by a number of nuclear families unified by kinship ties. It is basically a group of women related by kinship and headed by a man. There are no moieties, clans or lineages, neither exist rights or obligations passed on by particular lineal descent.

Post-nuptial residence is with the woman's parents (uxorilocality), at least temporarily. Many heads of extended families look for keeping a great number of women with them, even adopting daughters of deceased men usually called "brothers" by them. They try to arrange marriages for these girls and women with the aim to attract sons-in-law who shall live at least one or two years with their fathers-in-law rendering various kinds of service. If the head of a family has a lot of prestige, he can manage that his sons-in-law stay definitely with his group, therewith increasing the number of collaborators and recruiting followers to organize a village faction.

Leadership is established without fixed rules, but suffered some changes with indigenist politics. The principal traditional criterions for assuming leadership (individual qualities and the support of followers by consanguinity and affinity) became less important compared to demands for knowing to deal with the world of the whites. In the first place, this refers as well to the ability to establish good relations with government agencies and derive advantages from this for local communities as to individual qualities (knowledge of Portuguese and diplomatic talent, among others).

Every village has its own chief (cacique or capitão), but there are villages with more than one because of rivalries between various extended families. Some chiefs try to expand their influence to neighbouring villages, but their authority is quite unstable and can be contested any moment by rivals from the same village. In these power plays the indigenist agency uses to interfere by promoting their own favourites who can be weak characters without real political basis in the villages.

Gender relations

Gender relations are characterized by unbalances in favour of men, what is principally manifested in politics and education: leaders normally are males, and education for boys is more liberal than for girls. In the economic and cosmological spheres female activities are more related to agriculture than male activities, which are more turned to hunting.

The traditional division of labour by sex nowadays is no more so clearly defined as in former times, remaining ever less typical "male" activities, which currently are only hunting and preparing the clearing ground. The women did not yet succeed in conquering the political arena, staying at the edge of political meetings and continuing to influence the men politically in the domestic sphere. It is principally in sexual relations that the women normally take the initiative.

As for personal names, nowadays prevail the Christian-Portuguese ones. In general, only persons with more than 60 years still have indigenous names.

Material Culture

The Guajajara gave up the major part of their material culture, still producing some basketry and hammocks for domestic use and commercialisation. With incentives from Funai since the 1970s, the Guajajara returned to produce feather work, adornments, weapons and basketry by remembering older patterns and designs and by imitating models of other indigenous peoples, finally creating a new style of their own, which nowadays can easily be identified. By this way, the Guajajara also returned to use body painting both on festive and ritual occasions and for political demonstrations.

Cosmology, mythology and rituals

The traditional Guajajara cosmology is typical for Tupi-Guarani peoples and differentiates between four categories of supernatural beings who receive the generic denotation karowara: (1) the creators or cultural heroes who are responsible for the creation and transformation of the world, being Maíra and the twins Maíra-ira and Mucura-ira the most important and Zurupari, the creator of plagues, insects, poisonous snakes and spiders, a very feared cultural hero; (2) the "lords" of the forests (Ka'a'zar), the waters (Y'zar), the game (Miar'i'zar) and the trees (Wira'zar) who are hostile and very feared for their malign power; (3) the azang, errant spirits of the dead, also being very feared; and (4) the piwara, animal spirits. Many Guajajara do not believe any more in these beings because of missionary activities.

The mythology is a mixture of Tupi, European and African motives. There is, for example, a myth with the Cinderella motive and the figure of Zurupari. There are three principal categories of myths: (1) myths of cultural heroes; (2) myths which indicate a kind of moral; and (3) animal myths. In all the myths registered so far, the role of Maíra stands out. One very important myth for explaining the world from a Guajajara point of view is the one about the twins Maíra-ira and Mucura-ira.

The mythical motive of the twins is common among various Tupi peoples. For the Guajajara, they are cultural heroes, side by side with Maíra-father, although they do not have the same father. While Maíra-ira (Maíra-son) is of divine origin, Mucura-ira, just as his father, is of animal origin.

The myth tells about an odyssey through a world full of challenges and dangers, from the first moments in the mother's womb to the final encounter with Maíra. Their greatest challenge is their survival among the "jaguars" that are cannibals and kill the twins' mother, but these take a brutal revenge on them. During some years both learn to overcome all natural and supernatural perils, but Mucura-ira suffers more because of his "human" nature.

The myth is full of references to everyday life of the Guajajara and explains a great part of their world as, for example, their "condemnation" to agriculture by Maíra because of a kind of "Fall of man" (one moment of suspicion of Maíra's powers by a woman). But it also can be interpreted in terms of conflicts, which emerged and were overcome, as a kind of mythical representation of the conflicts within Guajajara society and with other peoples.

The great traditional rituals are in decline since a long time. In former times, the most important was the Honey Feast (zemuishi-ohaw), which took place in September or October, during the dry season, and which necessitated some months for preparations. It had a very important function for good relations between the villages, but nowadays it is rarely celebrated and only in few villages.

The Maize Feast (awashire-wehuhau), also called the "shaman's feast", has taken place every year in the rainy season, during the growing period of this plant. Its purpose was to guarantee a good harvest and protect the maize against actions of the azang. Therefore, its principal trait was shamanism.

The Moqueado ritual, which took place at the same occasion as a part of the Maize Feast, marked the end of puberty for the participating adolescents. The Moqueado is still practiced at irregular intervals, but became a bit profane, often remaining only the culinary part of the ritual for complementing political meetings.

Among the principal causes for abandoning these festivities figures the lack of time to prepare and realize them, taking into consideration the Guajajara's integration in the regional economy, besides the oblivion of many shamanic songs. The lifecycle of a person still uses to be accomplished by a series of rituals. Among these, the rituals of initiation, especially those of the girls, are the most sumptuous and richest in symbolic meanings. Moreover, there is a series of rituals for asking Maíra's permission to plant, Miar'i'zars to hunt and Y'zars to fish.

Shamanism

Shamanism is in decline, too. In some villages it even disappeared. In former times, the majority of men tried to become shaman at any price, but few were successful and got fame. The power and reputation of the shamans depended upon the number of supernatural beings they were able to "call". Well-known shamans even could become powerful leaders.

Shamanism is almost exclusively a male activity. The shamans' principal function is to heal and to celebrate the Maíra Feast and the mesada, a ritual of offerings in favour of sick persons. Shamanism normally is seen as ambiguous, because the shamans' powers can be used for both positive and negative ends.

Note on the sources

Ethnological texts have focused the Guajajara without exception by the prism of interethnic contacts, beginning with the book The Tenetehara Indians of Brazil - A Culture in Transition, by Charles Wagley and Eduardo Galvão, first published in English and based on fieldwork made in the 1940s, studying their culture in transition to a back-lands way of life. In this classic ethnographic study the two authors forecast equivocally the disappearance of the Guajajara as a distinguished group for the 1960s.

Mércio Gomes, on his part, investigated in his doctoral thesis, defended at the University of Florida in Gainesville in 1977, the history of the relations of the Guajajara with the whites since the colonial period in the light of a Neo-Marxist analysis and presents a theory to explain the persistence of their culture.

In the 1980s concentrate the articles of Edson Diniz, which make references among them repeating the authors already cited without making any innovative contribution. More recently, the books and papers of Peter Schröder present principally the situation of the Guajajara since the late 1980s. In 1993 he published his doctoral thesis, defended at Bonn University in Germany, about the development of a political movement among the Guajajara, using a multicausal approach.

The book O filho de Maíra (1997), by Carlo Ubbiali from CIMI-MA, is a subjective and very political presentation of Guajajara culture by a biographical approach, principally describing the life of one leader. An even more recent monograph is Claudio Zannoni's master thesis, defended at UESP (State University of São Paulo) in Araraquara and published in 1999 with the title Conflito e coesão: o dinamismo tenetehara. In this book, Zannoni emphasizes mythology and rituals for a better comprehension of the dynamics of Guajajara society in view of conflicts with the whites.

The most recent books about the Guajajara are O índio na história: o povo Tenetehara em busca da liberdade (2002), by Mércio Gomes, and Territórios em confronto: a dinâmica da disputa pela terra entre índios e brancos no Maranhão (2002), by Elizabeth Coelho. The last one is the text of a doctoral thesis, defended at UFC (Federal University of Ceará) in 1999, about the conflict of São Pedro dos Cacetes, while Gomes' book certainly is the best publication up to now about the history of the Guajajara.

The book Cauiré Imana, by Olímpio Cruz, describes in a belletristic style the Guajajara revolt against the Capuchin mission in 1901. With regard to Guajajara language, there are principally the studies of David Bendor-Samuel, Max Boudin, and Carl Harrison. Peter Schröder elaborated an exhaustive bibliography about the Guajajara, which can be consulted in the Internet.

There exists a documentary about the Alto Alegre conflict, and in the documentaries by Jürgen Dieckert and Jacob Mehringer about the Canelas, presented both in German TV and by the regional representative of the Globo channel in São Luís, there are many sequences with the Guajajara.

Sources of information

- BARATA, Maria Helena. Tupi-Guarani e Jê Timbira : articulações étnicas em processo. Brasília : UnB, 1999. (Tese de Doutorado).

- BARROS, Marcelo. Conflito de terras em áreas indígenas : o caso Guajajara/ São Pedro dos Cacetes. Desenvolvimento & Cidadania, São Luís : Instituto do Homem, n. 5, p. 15-7, 1992.

- BENDOR-SAMUEL, David Harold. Hierarchical structures in Guajajára. Londres : Univ. of London, 1966. 305 p. (Ph.D. Dissertation)

- CONSIGLIO, Vittorio. Fontes missionárias e história indígena : um inventário analítico sobre textos jesuíticos nos arquivos romanos referentes a missão em Maranhão e Grão-Pará, séculos XVII-XVIII. São Paulo : USP, 1997. 263 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CRUZ, Olímpio. Cauiré imana : o cacique rebelde. Brasília : Thesaurus, 1982.

- DINIZ, Edson Soares. Convívio e dependência : os Tenetehára-Guajajára. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, v. 69, p. 117-27, 1983.

- --------. Os índios Tenetehára-Guajajára e seu convívio com os regionais. Marília : Unesp, 1982. (Publicação Avulsa, 38 - Série Etnologia, 2)

- --------. Os Tenetehára-Guajajára : convívio e integração. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 27/28, p. 343-53, 1984/1985.

- --------. Os Tenetehára-Guajajára e a sociedade nacional : avaliação das relações intersocietárias. Marília : Unesp, 1988. 47 p. (Séries Monográficas, Etnologia, 5)

- --------. Os Tenetehára-Guajajára e a sociedade nacional : flexibilidade cultural e persistência étnica. Belém : UFPA, 1994. 77 p.

- --------; CARDIA, Luís Maretti. A situação atual dos índios Tenetehára. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 22, p. 79-85, 1979.

- GALVÃO, Eduardo. Diários Tenetehára (1941-1942). In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Diários de campo de Eduardo Galvão : Tenetehara, Kaioa e índios do Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1996. p. 25-174.

- GOMES, Mércio Pereira. The ethnic survival of the Tenetehara indians of Maranhão, Brazil. Gainesville. : Univ. of Florida, 1977. 295 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. O índio na história : o povo Tenetehara em busca da liberdade. Petrópolis : Vozes, 2002. 632 p.

- --------. Porque os índios brigam com posseiros : o caso dos índios Guajajára. In: DALLARI, Dalmo de Abreu; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da; VIDAL, Lux B. A questão da terra indígena. São Paulo : CPI-SP, 1981. p. 51-6. (Cadernos da Comissão Pró-Índio, 2)

- GUIMARÃES, Francisco Alfredo Morais. Vai-Yata-In (União de todos) : uma proposta alternativa no ensino da temática indígena na sala de aula. Salvador : UFBA, 1996. 256 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- HARRISON, Carl H. Poetry in Guajajara. Notes on Translation, s.l. : s.ed., v. 13, n. 3, p. 50-1, 1999.

- PERES, Carlos A. Indigenous reserves and nature conservation in Amazonian forests. Conservation Biology, Boston : Blackwell Scientific Publ., v. 8, n. 2, p. 586-8, jun. 1994.

- SCHADEN, Egon. Persistência e mudança da cultura Tenetehára. In: --------. Aculturação indígena : ensaio sobre fatôres e tendências da mudança cultural de tribos índias em contacto com o mundo dos brancos. São Paulo : Edusp, 1969. p. 145-78.

- SCHRÖDER, Peter. Cana Brava e São Pedro dos Cacetes : um conflito em extinção. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991-1995. São Paulo : ISA, 1996. p. 449-52.

- --------. Die Guajajara kampfen um ihr land. Brasilien Nachrichten, s.l. : s.ed., n. 111, p. 53-4, 1992.

- --------. Kein ende der konflikte um das land der Guajajara : Cana Brava 1991-1993. Brasilien Nachrichten, s.l. : s.ed., n. 115, p. 13-23, 1994.

- --------. União e organização : Zur Entstehung modernen indigenen Widerstands in Brasilien; eine vergleichende Untersuchung anhand von Fallbespielen. Bonn : Holos-Verlag, 1993. 301 p. (Mundus Reihe Ethnologie, 68)

- --------. Zur aktuellen Situation der Guajajara (Maranhao/ Brasilien). In: LAUBSCHER, Matthias S.; TURNER, Bertran (Orgs.). Volkerkunde Tagung 1991. 2. Regionale Volkerkunde. Munique : Akademischer Verlag, 1994. p. 105-111.

- --------. Zur geschichte eines landkonfliktes : Cana Brava in Maranhão. Brasilien Nachrichten, s.l. : s.ed., n. 109, p. 30-44, 1990.

- SOARES, Marília Lopes da Costa Facó. A perda da nasalidade e outras mutações vocálicas em Kokama, Asurini e Guajajara. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1979. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- UBBIALI, Carlo. O filho de Ma'ira. Quito : Abya-Yala, 1997. (Colección de Antropologia Aplicada, 13)

- WAGLEY, Charles. Cultural influences on population : a comparison of two tupí tribes. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (Ed.). Peoples and cultures of native South America : an anthropological reader. New York : The American Museum of Natural Story, 1973. p. 145-58.

- --------; GALVÃO, Eduardo. Os índios Tenetehara (uma cultura em transição). Rio de Janeiro : Imprensa Nacional, 1961. 236 p.

- --------. The Tenetehára indians of Brazil : a culture in transition. New York : AMS Press, 1969.

- ZANNONI, Cláudio. Mito e sociedade Tenetehara. Araraquara : Unesp, 2002. 320 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Wiriri piterere ipaw : a lagoa das bordunas. O conflito dos Tenetehara da região de Barra do Corda, MA. São Luis : UFMA, 1995. (Tese de Bacharelado)