Xetá

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- PR 69 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

The Xetá were the last ethnic group in the State of Paraná to have contact with the national society. In the 1940s, colonization fronts invaded their territory, drastically reducing it. Towards the end of the 1950s, the Xetá were virtually extinct. Today there are eight survivors, scattered in the States of Paraná, Santa Catarina and São Paulo.

Name, language and traditional territory

Xetá, Héta, Chetá, Setá, Ssetá, Aré, Yvaparé and even Botocudo are the denominations by which the Xetá may be identified in the literature, in voyager’s accounts and in documental sources that deal with the presence of indigenous peoples in the area that is today the State of Paraná.

However, Xetá is the term used by the anthropological literature since 1958 to identify them, even though, in the understanding of the survivors, the word has no meaning. Of the names listed above, héta (many, several) is the only one that belongs to the Xetá language, but is not used for self-identification.

Classified as part of the Tupi-Guarani linguistic family, the Xetá tongue is close to the Guarani dialectal group, especially the Mbyá, in its phonology and lexicon.

Original inhabitants of northwest State of Paraná, the Xetá traditional territory is located between the Ivaí River (left bank all the way to the Paraná River) and its tributaries, the Indoivaí River, the Duzentos e Quinze Creek (where many of the Xetá villages used to be located), the Antas, Veado and Tiradentes rivers, and the Maravilha Creek. Today in this area there are cities such as Umuarama, Cruzeiro do Oeste, Icaraíma and Douradina.

Early contacts

The first references to a people with cultural characteristics similar to those of the Xetá date from the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th. However, of all the references available, only the one made by Bigg-Wither leads us to suppose that the Xetá may be descendants of the Indians he called Botocudo.

The Xetá were the last ethnic group of the State of Paraná to have contact with the national society. Their first recorded contact took place on December 6, 1954, when six males, tired of constantly running away from the colonization fronts that had been advancing into their territory since the end of the 1940s reducing it drastically, visited the manager of the Fazenda (farm) Santa Rosa and his family, who had settled in the area used by the group since 1952 for hunting and gathering. The Indians then withdrew to the forest, returning a few days later with their families, including women and children. After that the visits become frequent.

In 1955, upon learning about the direct contact of the Xetá with the inhabitants of the Fazenda Santa Rosa, the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios – Service for the Protection of the Indian, Brazil’s first official organ for Indian affairs – (SPI) organized two contact expeditions to the area, known as Serra dos Dourados, one in October and another in November. Only the latter was able to find the group that visited the farm.

In February of 1956, a research expedition led by professor and anthropologist José Loureiro Fernandes, of the Federal University of Paraná, found two other villages in the forest. No member of the first group of Xetá took part in the expedition; neither they were sighted by subsequent expeditions. No other groups were found ever since. However, the family that had made contact with the people in the Fazenda Santa Rosa continued to visit it.

Official contact

Even though the first direct contact of the Xetá with the whites only took place officially in 1954, evidences of their presence in the region had been registered by the colonization fronts since the end of the 1940s. In 1949, 1951 and 1952, the SPI’s Paraná Office, with headquarters in the State capital, Curitiba, had sent members of the staff to try to find the Xetá. All of them failed, although they did find indications of the presence of Indians in the area, such as recently abandoned villages and objects. In 1952, two Indian boys were captured by land surveyors who worked in the region and taken to Curitiba, where they were raised by the local SPI inspector.

The occupation of the Xetá territory was carried out through the following fronts: (1) the expansion of coffee culture, upon which the colonization of northern Paraná was primarily based; (2) the opening and the implementation of cattle raising and agricultural establishments, and (3) the actions of the companies of colonization and immigration, which obtained cheap lands from the government, subdivided and sold them and promoted their occupation. At that time – when the first evidences of the presence of Indians in northwestern Paraná were found –, conflicts over rural property worsened in the State because the government, intent on occupying empty areas and promoting economic development, had made more land titles available than the amount of land that actually existed.

The contact of the Xetá with the Fazenda Santa Rosa resulted in two proposals for a reservation for the group, defended both at the State and federal levels.

The first was made in October of 1955 by State representative Antônio Lustosa de Oliveira, who owned the Fazenda Santa Rosa. He proposed the creation of a State Forest reservation, with part of it set apart for the Xetá. The area for the reserve would include part of the Xetá’s traditional territory. Although it was approved by the Paraná State Assembly, the proposal was vetoed by State governor Moysés Lupion, with the justification that that the State did not own enough land in the area.

The veto led to the conception of a new type of forest reservation in 1957, this time as a National Park, which would encompass the area previously proposed and also part of the Xetá territory. Professor José Loureiro Fernandes defended the creation of the Sete Quedas National Park, with an area for the Xetá within it.

The National Park was created on May 30, 1961 and although the Xetá habitat was recognized within it, its limits were to be defined by the SPI. The park, however, did not ensure territory for the Fazenda Santa Rosa group, as it did not protect the Xetá that avoided contact with the whites by hiding in the forest.

Quite the contrary: in fact, several Xetá children were taken to be raised by whites, and SPI agents took some of the Indians who lived in the vicinity of the Fazenda Santa Rosa to other indigenous areas in the State of Paraná. As for the Xetá that remained in what was left in their original territory, they wandered in the towns that sprung up in the region.

In 1981, because of the flooding of the Sete Quedas Falls by the lake of the Itaipu Hydroelectric Plant, a decree extinguished the Sete Quedas National Park. Once again, the Xetá were left with no land.

Between the first reports of their presence in northwestern Paraná and the creation of the Sete Quedas National Park, the Xetá were decimated. In fact, the surviving Indians say that they were already suffering the effects of the advance of the colonization fronts way before contact with whites was effectively established. Deaths were caused by food intoxication, poisoning, contagious diseases such as influenza, measles and pneumonia, as well as extermination through firearms and burning of villages, among other actions taken by those who invaded the Xetá territory. Since 1961 there has been no reference regarding the Xetá who avoided contact with whites.

The tragic consequences of the colonization policy of the Paraná State Government in the Serra dos Dourados region, along with the omission and negligence of the SPI as an organ directed towards the assistance and protection of indigenous peoples, resulted in the loss of the Xetá traditional territory and in the extinction of their society, of which only a few members have survived.

The Xetá population of the Serra dos Dourados region at the time of contact is unknown. Documental and bibliographical sources of that time estimate it in 250 individuals.

The surviving Xetá, however, claim that their people were approximately 400. They were grouped in small family nuclei, that is, extensive patrilocal families who lived in the oka-auatxu (large place, large village), made up of a tapuy-apoeng (large house). In these dwellings, where several families lived, many rituals were carried out, including the male initiation’s.

Because of internal conflicts and inter-ethnic confrontations with the Kaingang, and, later, with the white colonizers, the Xetá were forced to move around often, and the oka-kã (small place, camp), with their tapuy-kã (small houses), i.e., temporary dwellings, became the group’s main living arrangement.

Eight survivors

Currently the Xetá are eight individuals, three females and five males. All of them are relatives. It is possible that four more Xetá exist.

Differently from other indigenous peoples in Brazil, the surviving Xetá do not live in society, nor are grouped in a single territorial space. They do not share the same cultural codes either. From hunters and gatherers they have become wage earners – public employees, household servants and bóias-frias (rural workers who live in urban areas and go daily to work in the fields). From occupants of a traditional territory, they now live in lands that belong to the Kaingang and Guarani, or as tenants.

Spread around by the colonizers since childhood or puberty, the surviving Xetá are scattered in the States of Paraná, Santa Catarina and São Paulo. They have 42 descendants, many of whom are married to Kaingang and Guarani Indians and to non-Indians.

The eight survivors are:

1) Kuein Manhaa’ei Nhaguakã Xetá, 65-years old, lives in the Rio das Cobras Indigenous Area, municipality of Nova Laranjeiras, State of Paraná;

2) Tucanambá José Paraná (Tuca, as he is known among the whites, or Anambu Guaka [red macaw, or nhambu, a bird], the name given by his parents), 52-years old, lives in the Rio das Cobras Indigenous Area, municipality of Nova Laranjeiras, State of Paraná;

3) José Luciano da Silva (Tikuein, as he is known by the whites, or Nhangoray [raccoon], the name given by his parents), 48-years old, resident in the São Jerônimo Indigenous Post, municipality of São Jerônimo da Serra, State of Paraná;

4) Maria Rosa à Xetá (Ã, as she is known, or Moko [anteater], the name given by her family), 48-years old, resident in the Guarapuava Indigenous Post, municipality of Turvo, State of Paraná;

5) Maria Rosa Tiguá Brasil, (Tiguá, as she is known, or Irajo [fish]), 48-years old, resident in the city of Umuarama, State of Paraná;

6) Ana Maria (Tiguá, as she is known, or Tunkaajo [large toucan], 44-years old, resident in São Paulo, State of São Paulo;

7) Tiqüein Xetá (Karombe [turtle]), 37-years old, resident in Nova Tebas, State of Paraná;

8) Rondon Xetá (Moha’ ay [ferret]), 34-years old, resident in the Xapecó Indigenous Post, municipality of Xanxerê, State of Santa Catarina

The eight survivors recognize each other and identify themselves as Xetá. Three of them (Kuein, Tuca and Tikuein) speak fluently their people’s language, while one of the women, Ã, understands it but speaks only Portuguese. The others – as well as all their descendants – cannot speak Xetá.

Until 1996, some of the survivors were not aware of the existence of other Xetá and of the kinship ties they have with them.

Xetá Meeting

In August of 1997, urged by the eight remaining Xetá, the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) sponsored in Curitiba the "Encontro Xetá: Sobreviventes do Extermínio" (Xetá meeting: survivors of extermination), when they met each other and spoke of themselves, their past and their present and the prospects for a better future for them and their descendants.

As a result of the meeting, the Xetá prepared a document in which they demand, from the national society and from the government, their recognition – and of their descendants – as survivors of the Xetá ethnic group. They also demanded attention from the Funai and a compensation in money and lands for the tragedy that fell upon their people and for the losses they themselves have suffered along their lives. Another demand was the rectification of their official names, with the recognition of their indigenous names and of their parents’.

The remaining Xetá have today the challenge of attempting to recover part of the many things that, under different pretexts, have been taken from them in a not so far past. Being close to each other and informed about each others’ lives is one of their main objectives.

Note about the sources

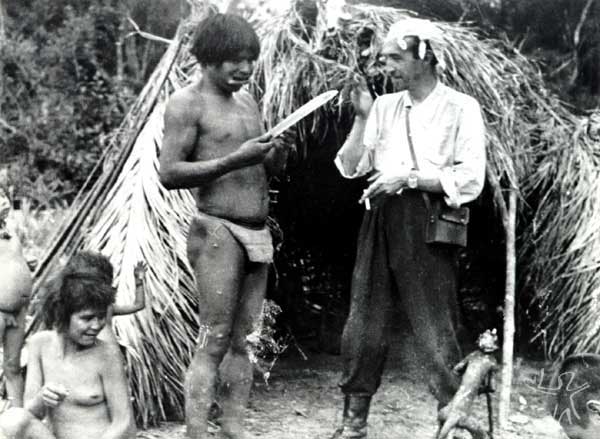

The first ethnographic reports regarding the Xetá were made by anthropologist José Loureiro Fernandes, who organized surveying expeditions between 1955 and 1961. His articles were centered in the group’s material culture, technology and costumes. Federal University of Paraná’s movie technician Vladimir Kozák has also written articles and published a book on those same topics.

Regarding the Xetá material culture, there are also the works by Annete Laming-Emperaire, Maria José de Menezes and Margarida Andreata, published in 1964 and 1978, and Tom Miller’s study, of 1979, which dealt specifically with lithic technology.

In addition to those, there are the final monograph for the Course of Specialization in Social Anthropology by Maria Fernanda Maranhão presented to the Department of Anthropology of the Federal University of Paraná in 1989, about Xetá ethno-archaeology, and an article by Cecília Maria Vieira Helm, published in 1994, about the ethnographic sources that register the extermination of the Xetá.

Regarding the Xetá language, there are works by Cestimir Loukotka, published in 1929 and 1960, Mansur Guérios, in 1959, and Aryon Dall’Igna Rodrigues, in 1978.

More recent works include research reports, a few articles and a Master’s degree thesis defended at the PPGAS/UFSC by Carmen Lucia da Silva, who examines the remembrances of the survivors regarding the contact and the extermination of the Xetá society.

In addition to bibliographical material, there exists audio-visual material as well: a 16-mm film produced in the 1960s by Vladimir Kozák directed by José Loureiro Fernandes and photos made by Vladimir Kozák and José Loureiro Fernandes in the 1950s and 1960s, by Carmen Lucia da Silva in 1996-1999, and by Márcia Rosato in 1997

VIDEOS

Sources of information

- BIGG-WITHER, Thomas P. Novo caminho no Brasil meridional : Província do Paraná. Rio de Janeiro : J. Olympio, 1974. (Documentos Brasileiros, 162)

- BORBA, Telêmaco M. Observações sobre os indígenas do Estado do Paraná. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 7, p. 53-62, 1904.

- FERNANDES, José Loureiro. A dying people. Bulletin of the International Commitee on Urgent Anthropological Research, s.l., n.2, 1959.

. Os índios da Serra dos Dourados : os Xetá. In: REUNIÃO BRASILEIRA DE ANTROPOLOGIA (3a., 1959, Recife-PE). Anais. s.l. : s.ed., 1959. p. 27-46.

Publicado também no Bulletin of the International Commitee on Urgent Anthropological Research, Vienna, n.5, p. 151-4, 1962

. Le Peuplement ou nordouest du Paraná et les indiens de la "Serra dos Dourados". Boletim Paranaense de Geografia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba : UFPR, n.2/3, p. 79-91, jun. 1961.

. Les Xetá et les palmiers de la forêt de Dourados : contribution à l’ethnobotanique du Paraná. In: CONGRÈS INTERNATIONAL DES SCIENCES ANTRHROPOLOGIQUES ET ETHNOLOGIQUES. Actes. v. 2. Paris : s.ed., 1960. p. 38-43.

- HELM, Cecília Maria Vieira. Povos indígenas e projetos hidrelétricos no estado do Paraná. Curitiba : HP, 1998. 25 p.

. Os Xetá : a trajetória de um grupo tupi-guarani em extinção no Paraná. Anuário Antropológico, Rio de Janeiro : Tempo Brasileiro, n. 92, p. 105-12, 1994.

. Los Xeta : la trayectoria de un grupo Tupi-Guarani. In: BARTOLOME, Miguel A. (Coord.). Ya no hay lugar para cazadores : processo de extincción y transfiguración étnica en America Latina. Quito : Abya-Ayala, 1995. p. 109-22. (Biblioteca Abya-Yala, 23)

- KOZÁK, Vladimir. Os índios Héta : peixe em lagoa seca. Boletim do Instituto Histórico, Geográfico e Etnográfico Paranaense, Curitiba, v. 38, p. 11-120, 1981.

- LAMING-EMPERAIRE, Annete; MENEZES, Maria José; ANDREATA, Margarida Davina. O Trabalho da pedra entre os Xetá da Serra dos Dourados, Estado do Paraná. Coleção Museu Paulista: série ensaios, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, n.2, p. 19-82, 1978.

- MARANHÃO, Maria Fernanda C. Etnoarqueologia Xetá. Curitiba : UFPR, 1989. (Monografia especialização em Antropologia Social).

- MOTA, Lúcio Tadeu. O aço, a cruz e a terra : índios e brancos no Paraná provincial 1853-1889. Assis : Unesp, 1998. 530 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

(Org.). As cidades e os povos indígenas : mitologias e visões. Maringá : Eduem, 2000. 47 p.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon D. A Língua dos índios Xetá como dialeto Guarani. Cadernos de Estudos Lingüisticos, São Paulo : s.ed., n.1, p. 7-11, sep., 1978.

. Línguas brasileiras : para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo : Loyola, 1986.

- SILVA, Carmen Lúcia. Sobreviventes do extermínio : uma etnografia das narrativas e lembranças da sociedade Xetá. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1998. (Dissertação de Mestrado).

- SIMONIAN, Ligia Terezinha Lopes (Org.). Arquivo Kaingang, Guaraní e Xetá. Ijuí : Fidene, 1981. 114 p. (Cadernos do Museu, 10)

- Os Xetá da Serra dos Dourados. Dir.: José Loureiro Fernandes. Vídeo cor, VHS-NTSC, 47 min., década de 60. Prod.: Vladimir Kozák.