Waimiri Atroari

- Self-denomination

- Kinja

- Where they are How many

- AM 2394 (PWA, 2022)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

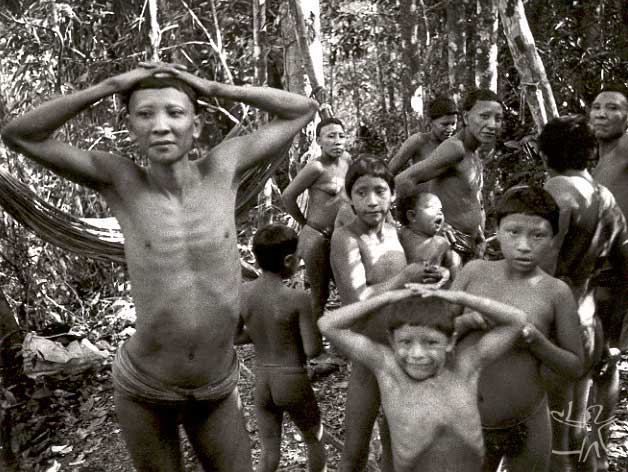

The Waimiri Atroari have long held a special place in the Brazilian imaginary as a warrior people who confronted and killed any outsiders who tried to enter their territory. This image led government authorities to transfer the responsibility for building a highway through their lands to the Brazilian Army, which used repressive military force to control the Indians. This confrontation culminated in the near extinction of the Kinja people (the name used by the Waimiri Atroari for themselves). The invasion of their lands intensified when a mining company began excavations and when a hydroelectric dam was constructed, which flooded part of their territory. But the Waimiri Atroari faced up to these challenges and negotiated with national Brazilians, so that, today, they enjoy secure reservation boundaries, cultural vigor, and population growth.

Waimiri Atroari, the Kinja people

The Waimiri Atroari recount that, in ancient times, there were two groups known as Iky and Wehmiri. The Iky occupied the headwaters and had light-colored skin, while the Wehmiri lived near the mouth of the river and had darker skin. These groups were as much at home on the river bottom as they were on land, since they were relatives of Xiriminja, a mythological entity that lives underwater. The Waimiri Atroari say that Iky's daughter was the one who gave a penis to their ancestors. Thus begins one of the origin stories of the Waimiri Atroari. They call themselves Kinja (“true people”), in contrast to others: the kaminja (non-indigenous people), the makyma (left-handed people), and the irikwa (the living dead). The name “Waimiri Atroari,” as they are now known by non-Indians, originated with the Indian Protection Service (SPI) in the early twentieth century. Despite this compound name, it refers to a single group, the Kinja people.

The Waimiri Atroari ancestors Tahkome and Nysakome, and the domains of land, air, and water

According to the Kinja, all the animals and mythological beings that inhabited the earth in ancient times were human beings, who lived in the midst of their ancestors. One day, it began “raining” stones, and everyone thought the world was going to end. However, one of the houses was supported by a center post made of pau d'arco, a strong kind of wood that withstood the stones' blows. Several families lived together in this house, who gave rise to the ancestors of the current Waimiri Atroari. Thus, the genesis of the Kinja was marked by a division between the time before and the time after the stone “rain.” Nowadays, they say that they are the second-generation descendants of the people who survived the storm, protected by the center post holding up their house.

The ancient Waimiri Atroari are known as Tahkome (male) and Nysakome (female). Tahkome is a term that can also refer to a very distant past (the time of these ancestors), when everyone lived together in a state of equality and all were human, although some had supernatural powers.

During this era, animals did not yet exist, and people lived off of the fruits and tubers found in nature. Mawa, a supernatural being who was also a person, lived on earth and furnished the Kinja with all the food they needed. Mawa was one of those responsible for transforming some people (who broke rules) into animals and for supplying certain cultivated plants in their gardens.

One day, tired of living with others on earth and worried the sky would fall, Mawa decided to leave. He asked the tortoise to shoot a string of arrows upwards so they formed a stairway leading up to the sky. By climbing this chain of arrows linking earth and sky, Mawa managed to reach the upper domain, where he took up residence. Some people also tried to climb up the stairway, but Mawa cut it off, and they all fell back down. Those who got caught in the trees were transformed into various species of monkeys. Since Mawa is in charge of regulating the forces of nature, he appears in several narratives about the origin of thunder, day and night, and the great flood.

The current Kinja live on earth, where they choose sites to build their settlements. Around the collective house they plant their gardens. Beyond these lies the forest, which is the domain of game animals. This is a dangerous place for the Waimiri Atroari, especially for women and children, who avoid entering it without accompaniment.

The forest is home to the irikwa (the living dead), the iamai (creatures resembling bats), and the ianana, all of which are terrible beings that drink the blood and eat the flesh of the Kinja. Humans should never look at irikwa or iamai; if they do, they are doomed to die as their vital energies slowly drain away. Ianana is an entity that lives in the trunks of angelim trees. He used to kill and eat Kinja people. One day a Kinja discovered where he lived and set fire to the tree. The ianana's son survived, so the man took him back to the village and raised him as a Kinja. He had great luck in hunting, which made everyone curious to know why. He explained how he hunted, but no one believed him. Feeling discredited, he wandered into the forest, where he met his grandmother. She told him the whole story of his life, which made him decide to go back to living in the forest.

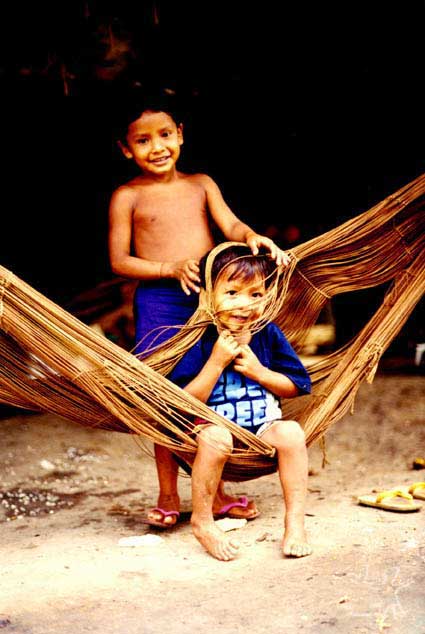

The aquatic world is where fish are found, another important source of protein for the Waimiri Atroari. This domain is also home to the xiriminja, semi-human entities that inhabit the bottom of rivers and lakes. Long ago, the xiriminja offered their daughters in marriage to the Kinja. In this era, men did not have penises, until one of the xiriminja's daughters offered this sex organ to the Kinja. The extension of relations between these two peoples benefitted the Waimiri Atroari by enriching their material and immaterial culture. The xiriminja taught them how to weave baskets (with many kinds of designs), how to perform certain songs and dances for male initiation rituals, and how to plant the cuttings of various edible plants they gave to the Kinja.

Although they occupy distinct realms, mythological and human beings maintain extensive interrelations. The different domains penetrate each other, constituting the whole of the Waimiri Atroari universe.

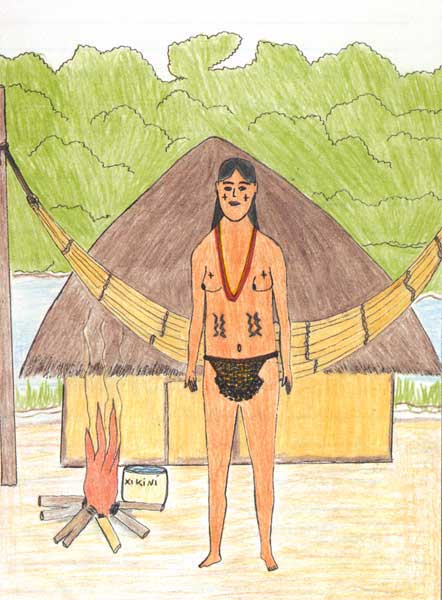

Mydy taha, villages

The phrase mydy taha, literally “big house,” refers to the communal residential structure, built in a circular format, where most of the village members live. The term also designates the space that makes up the village, both the living quarters and its immediate surroundings, including the gardens. The mydy taha is an important space for the Waimiri Atroari, since it serves not only as a settlement but also as a ritual space during their festivities. New villages are founded according to the community's needs, such as an increase in the population, the exhaustion of garden soils, or a scarcity of game.

Mydy taha are located near large rivers and seasonal streams. Each village enjoys economic and political autonomy, since no centralized power exists. The formation of a new village takes place gradually, relying on a prestigious person known as a mydy iapremy, “village master,” to mobilize a set of domestic groups to open up a new space. First, they choose a site within the region destined for the settlement, and then begin work on the gardens. When the crops appear, people start building a large circular communal house, the mydy taha. The structure will house various domestic groups, made up of relatives that include affines (in-laws) and cognates (kin). Each family has its own hearth and specific section.

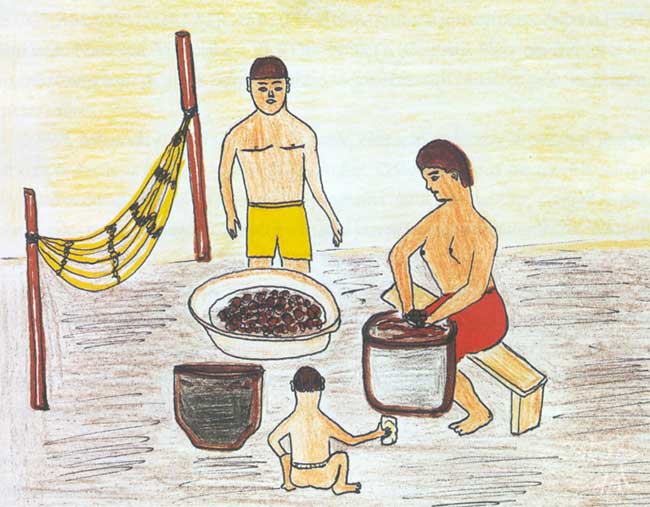

The economic activities of a village are based on hunting, fishing, agriculture, and gathering wild fruits. Men are responsible for hunting game, which may take place during the day or at nighttime. Both sexes are allowed to fish, and often the whole family may go out fishing. Another activity that is undertaken by everyone in a family is gathering wild fruits. The greatest division of labor occurs in agriculture. Men are the ones who fell trees, burn them, and clear the gardens, while women are the ones who harvest the crops. Both take part in planting the gardens, a collective activity involving all the families, who also collectively divide up the produce. The crops include bitter manioc, sweet manioc, several types of sweet potatoes, yams, and certain fruits.

Besides these garden crops, the Waimiri Atroari menu includes many species of fish and animals, such as tapirs, howler monkeys, coatis, pakas, wild pigs, curassows, and trumpeter birds, among others. Not all animals and fishes may be eaten on a daily basis. Various food restrictions are imposed on individuals at significant points in their lives, such as birth, rites of passage, first menstruation, and purification before and after a war.

The preferred form of marriage is between people who are classified as cross-cousins. This confers a new status on the couple, who, besides attaining full citizenship, form a new domestic group within the local group. Family responsibilities become accentuated upon marriage: a man is expected to maintain gardens and provide food for his family, while the woman takes charge of cooking food and caring for their children.

The division of labor varies according to sex, age, and civil status. Tasks increase as a person ages, until he or she becomes elderly, when they decrease. Despite the division by sex, men often help their wives butcher game and fish, care for children, and prepare manioc meal for domestic group consumption.

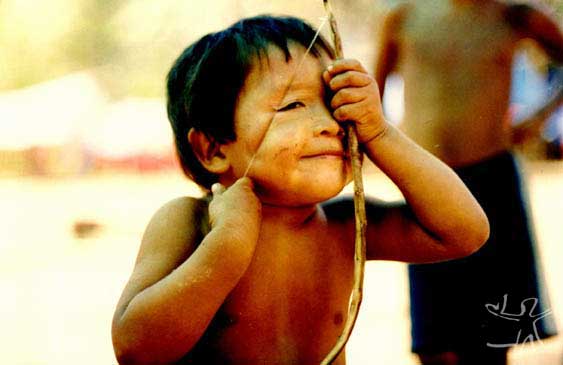

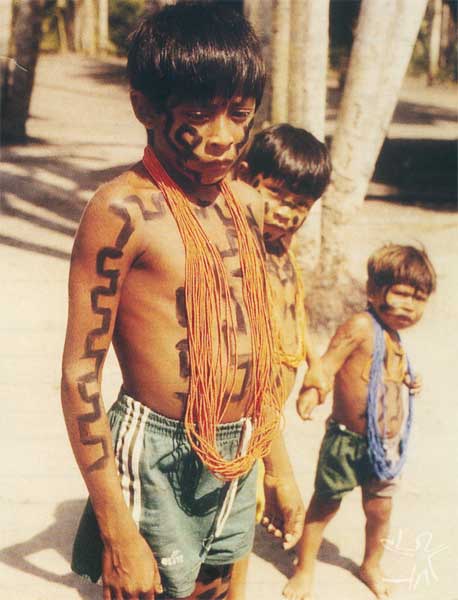

The upbringing of a Waimiri Atroari individual varies according to sex. Boys and girls are taken care of by their mothers and are encouraged to imitate the tasks appropriate to their gender, until they are approximately four years old. At this age, the boys go through an initiation ritual, marked by a specific festival for commemorating their new status. Members of this age grade undertake activities traditionally associated with their gender. The main rite of passage for girls occurs upon their first menstrual period.

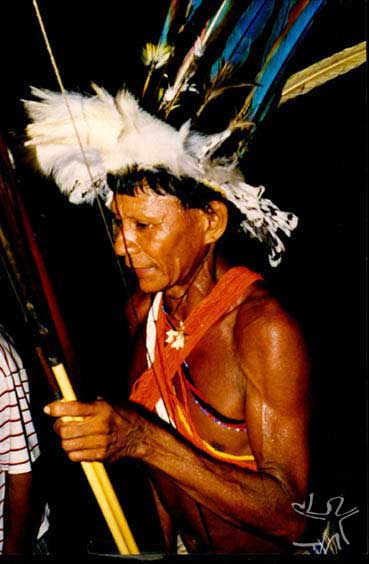

Another constant activity in the daily life of a village is the production of material artifacts. The Waimiri Atroari are expert weavers. All forms of basketry are made by men, who teach the skill to youths when they are old enough to get married. Men weave the items that women use in their work, such as the wyiepe (burden basket), the matepi (a tube for wringing manioc pulp), the matyty (a double-layered basket), and the wyre (fire fan). Women receive these artifacts from their husbands or fathers-in-law. Men also make the pakra (a covered basket for storing arrow-making materials) for personal use, as well as the bows and arrows they use in hunting and fishing. Most Waimiri Atroari baskets are illustrated with designs that they inherited from some mythological beings and their ancestors. A weaver's apprenticeship begins with simple figures, which become more difficult according to his age and skill level, until he earns permission to weave the most complex designs, granted only to elderly men.

Women weave birthing hammocks from the fiber of the burity palm, as well as bracelets, necklaces, and fire fans. Previously, they used to fashion pottery and griddles from clay, which nowadays have been replaced by ones made of aluminum and iron.

Various objects can be found in current Waimiri Atroari villages that formerly were not part of their material culture Undoubtedly, the first items introduced were cutting tools and clothes. In the recent past, a little over thirty years ago, men were usually seen wearing loincloths made of titica vines. Women made apron-skirts out of tucum palm fibers, decorated with bacaba seeds. These were the Kinja's traditional items of clothing. Nowadays, men usually wear pants, and women, skirts.

Maryba and the origin of festivals

At various times of the year, the Waimiri Atroari interrupt their daily activities to hold their maryba, or festivals. There is no specific calendar for putting on maryba, although they generally occur during slack periods when villagers are not preparing or planting gardens or involved in other collective labor on dates chosen by song leaders known as eremy.

The term maryba can be translated as festival, song, or dance. It is both a ritual moment and a gala one, when the community suspends everyday existence and is transported to another time and space. Maryba hold a special significance in Waimiri Atroari life as a time when various local groups gather together to establish and reaffirm alliances among themselves and with other settlements.

Certain stories are sources of explanation for how festivals arose. The best known ones are the following:

During the era of the tahkome (ancestors), the Kinja did not hold festivals and did not know how to sing or dance. Xiriminja, who had granted wives to the tahkome, taught them a maryba to sing on occasions when he came to visit his grandson. Xiriminja sent a message ahead asking that no one come near his descendant, since he wanted to make sure that the child had the distinctive features of water people, webbed fingers. When he arrived in the village with all his followers, including anacondas and other xiriminja people, the Kinja were frightened. However, the villagers had already heard the visitors' songs as they emerged from the water, and now they could watch the visitors' dances. Everyone began singing and dancing together.

Inside the communal house, a child who was very curious and naughty wanted to look at Xiriminja's grandson. When the child saw that the grandson's hands looked like a duck's foot, he spread the fingers open and ripped the membrane. When Xiriminja found out, he became irate and went back home. Because of this, the Kinja's ancestors only learned a few of the festival songs. These songs and dances are now performed during the maryba of male initiation. No pregnant woman is allowed to participate in these rituals, lest Xiriminja think that she is carrying his grandson.

In another myth, a tahkome man was hunting and stopped to take a nap. When a drop of water fell on his eyelashes, he woke up and saw a woman in front of him. She was a weriri kyrwaky, the parrot's daughter. The man aimed his bow and arrow to shoot her, but her father intervened and promised his daughter in marriage. The man married the parrot woman and brought her to his village. There she taught various songs and dances to the Waimiri Atroari. After living there a long time, weriri kyrwaky missed her father and began to sing in the garden to get his attention. Her husband, suspecting a ruse, killed her rather than let her get away. Ever since that time, the Kinja people have sung and danced all the maryba that they learned from their forebears.

Examples of festivals

The Waimiri Atroari spend several months getting ready for the festival celebrating male initiation. This ritual takes place when boys reach the age of three or four. The boys' fathers who belong to the same local group meet with male eremy (song leaders) to decide when to hold the festival. Once the date is chosen, each boy's father weaves a sort of calendar made of bamboo strips tied together with a thin vine. These strips represent the number of days left before the guests arrive at the village hosting the festivities. A mark is also made on the calendar with a knife indicating the day for picking bananas in time to ripen for making porridge.

The women are in charge of preparing all the food for the feasts. The culinary activities are organized by the mothers and grandmothers (both maternal and paternal) of the boys to be initiated. The men get busy making arrows and baskets. The arrows will be offered to the song leaders as a kind of payment for their services and to the paxira relatives to thank them for having shown up. The baskets will be used to serve the feast foods, especially smoked meat; some baskets will also be placed on each boy's head to ask that he have many dreams and that he become a good hunter and fisher.

When the calendar indicates the time is up, the fathers leave their village to issue invitations to their paxira (distant relatives who live in settlements apart from the group holding the festival). Nearby relatives come to the host village to help in preparations for the event.

The boys' fathers divide themselves up into groups according to the communities they will invite, where they will stay until the day set for the trip back to the host village. Expeditions involving all the inhabitants of the various villages are organized along the interlinking network of trails. During the trek through the forest, the men go hunting for game, which they smoke and preserve for the festival. In the camps, the travelers only eat wild fruits and low-quality cuts of meat. The boys' fathers carry burden baskets made of patawa palm leaves, which gradually get filled with meat, all the way to the village where the festival will be held.

When they get near the host community, the paxira relatives set up camp, where they will wait until the dawn before the festival, usually the next day. Shortly before daybreak, the eremy (song leaders) begin their melodies, waking up everyone. At a distance, the residents of the host village hear the songs and flutes and get ready to receive their guests.

The boys to be initiated are led outside the communal house and seated on a bench made especially for the occasion. Sometimes their unmarried adolescent sisters accompany them in this reception. All the paxira relatives enter the village clearing singing, following the fathers and eremy at the front of the crowd. With great fanfare, they circle around the boys, hand over the game to the hosts, and then head for the inside of the communal house, where they are given a reception of manioc bread and burity palmfruit porridge.

The festival cannot be organized without the presence of an eremy . The song leader is the one who confers with the boys' fathers and decides on the time when the festival will take place and who will direct all the activities during the ritual. To become a song leader, it is not enough to simply aspire to be one: it is necessary to be willing to spend a long period of apprenticeship under a more experienced song leader, to be disciplined, and to have a good memory. This activity can be exercised by both sexes. They are responsible for eliciting songs that link the ritual universe to the cosmogonic one. The lyrics refer to mythological animals, foods, and heroes, and are sung in an archaic language that is no longer used. The song leader's knowledge also encompasses the uses of herbal medicines, treatment of the ill, and assistance in childbirth in collaboration with relatives.

The Waimiri Atroari hold other kinds of festivals as well, such as one for the living dead and another for inaugurating a new house. The irikwa maryba, ritual of the living dead, takes place when a malignant spirit is approaching the village; the objective of the ritual is to calm the spirit down and make it go away. The irikwa maryba is also held after the death of a relative so that his or her soul does not stay around wandering in the world of the living. The irikwa are entities that live in the forest and are considered bad omens. If a Waimiri Atroari sees one, he or she is doomed to a slow, withering death, there being no cure for this type of contagion. The ritual of the living dead is performed whenever necessary, rather than following any periodic schedule.

The mydy maryba, new house festival, occurs when the local group completes the work of covering the roof and sides of the communal structure. The participants of this festival include the various domestic and local groups whom the “village master” (mydy iapremy) invited to assist the residents in constructing the new house. This festival is performed so good currents will flow through the house, so the irikwa will not come close, and so the building materials will last a long time.

Language

The Waimiri Atroari language, which they call kinja iara, “people's language,” belongs to the Carib linguistic family. All the Waimiri Atroari speak this language, it being the means of communication among themselves and the one used in reading and writing. Portuguese is considered a contact language, its use being restricted to the school in foreign language classes and to interethnic relations. The number of bilingual speakers is relatively low, involving about 20% of the population, the majority being males (youths and adults) who serve as intermediaries in relations between Waimiri Atroari society and other indigenous and non-indigenous societies.

Contact situation

The history of contact between non-indigenous societies and the Waimiri Atroari in the region where they have lived dates back to the seventeenth century. The first contacts occurred with the expansion of the mercantile and extractivist activities of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns, who wanted to secure their geopolitical territory. However, the official history of contacts with the Waimiri Atroari began in the late nineteenth century (1884) with João Barbosa Rodrigues, who declared himself to be the first “pacifier” of this people.

Barbosa Rodrigues traveled through various villages near the indigenous territory with the intention of enlisting guides and collecting data and reports about the Waimiri Atroari. He referred to them as the Crichanás, claiming that they were the ethnic group he encountered during the time of his expeditions, but that the “terrible and treacherous” natives who used to live in the region no longer existed. The rationale for this new denomination was that he wanted to create a new image of the indigenous people in this region. This would facilitate his mission of pacification and thereby promote friendlier contacts between Indians and non-Indians, whose relations at the time were extremely hostile.

The Waimiri Atroari witnessed the invasion of their territory by outsiders seeking to exploit various kinds of natural resources (animal pelts, Brazil nuts, rubber, rosewood, and so on). The Indians armed themselves with bows and arrows to repel these invaders. Word of the Waimiri Atroari's fearlessness reached the capital of the Amazonas province, and the government organized military expeditions to retaliate against the entire indigenous population. According to reports and documents of the era, the Waimiri Atroari's attempts to repulse invaders from their lands cost them many more lives than those lost by non-Indians.

After the turn of the century (1911), Alípio Bandeira, a representative of the Indian Protection Service (SPI, the Brazilian bureau of Indian affairs until 1967), traveled through the region surrounding the Rio Jauaperi in search of this people, who were now known as the Uaimirys. He found basically the same state of hostility, taking into account differences of scale and historical conditions, between indigenous and non-indigenous populations. In 1912, Alípio Bandeira established the first Indian attraction station on the Rio Jauaperi. Soon afterwards, he made his first friendly contacts with the Waimiri Atroari. From this time on, SPI coordinated the indigenist services and policies in the region – at least theoretically, since this government agency had little autonomy for enforcing the indigenist policies of the era.

During this period, the economy of the state government was based on extractivist activities. This meant that the indigenous population was considered an inconvenience to Brazilians who gathered natural medicinals and other wild plants and who viewed native lands as a huge storehouse of such resources. The government encouraged gatherers to invade areas occupied by native peoples. Denunciations of such invasions were treated as slander against the gatherers that was spread by people who wanted to prevent the growth of the state economy. Repeating scenes from the end of the prior century, the Waimiri Atroari reacted against the invasions of their territorial space by attacking and killing non-Indians, and the government organized more reprisals to avenge the deaths and punish their authors. The retaliations against the Indians were always disproportionate. They were unequal battles, first, in terms of weapons, one side using firearms, the other, bows and arrows. Furthermore, three hundred Brazilians were arrayed against a much smaller number of Indians, according to the reports of casualties on both sides. These were unjust wars in which one side attacked while the other defended itself. Given their reduced number of combatants, the Waimiri Atroari found themselves in the position of defending their territory, their honor, and their communities. Entire villages were decimated in surprise attacks, but even so, Indian warriors fought with supreme skill. Hence the reputation of the Waimiri Atroari as a fearless, warlike, wild, and remote people continued to grow, leading to myths about their social character.

In the late 1960s, the governments of Amazonas state and Roraima territory initiated construction of an overland highway between the cities of Manaus and Caracaraí. Knowing the history of conflicts between the Waimiri Atroari and Brazilians, the Amazonas Department of Transportation (DER-AM) asked the Indian Protection Service (SPI) to pacify the native people in the shortest time possible, to avoid possible confrontations with highway construction workers. The government was also in a hurry because of national and international protests against its plans to build the highway straight through the middle of Waimiri Atroari territory.

Shortly after scandals led to the termination of SPI, its successor, the National Indian Foundation (Funai), intensified contact activities through the Waimiri Atroari Attraction Campaign. The expeditionist Gilberto Pinto Figueiredo was put in charge of leading the pacification efforts. He conducted the contacts according to Funai's indigenist policies. He visited the indigenous villages, communicated with the residents through gestures, and traded “presents” (metal pots, knives, axes, machetes, utensils, and clothing) for objects made by the Waimiri Atroari. He created several attraction stations in strategic places for attaining his objective of attracting the Indians to locations distant from the highway. But DER-AM, the state agency responsible for work on the Manaus/Caracaraí road, considered the frontiersman's efforts to be too slow-paced. Due to pressures from Federal and state politicians, DER-AM wanted to conclude the construction project quickly, so it asked FUNAI to replace Figueiredo.

After Figueiredo was removed, the Italian priest Giovanni Calleri, from the Roraima church parish, assumed responsibility for the attraction of the Waimiri Atroari. The Calleri expedition consisted of eight men and two women. This was the first time that women participated in this type of work; their presence was supposed to lend a “normal,” family-like character to the expedition.

Their strategy was to follow river courses, which the priest viewed as neutral territory respected by the Indians. Father Calleri thought contacts would be easier with villages that were farther away from the crews of highway workers, reasoning that their residents “had not yet witnessed the arrival of white people.” However, his plans for beginning activities via the Rio Alalaú, where the most remote villages were located, were changed when it became necessary to placate the conflicts between the Waimiri Atroari and the workers. Calleri modified the trajectory of the expedition by initiating contacts along the Rio Santo Antonio do Abonari. The team spent five days in native territory and established contact with the residents of one community. However, at the end of the fifth day, the Indians killed almost all of the team members, of whom only one woodsman survived.

With the extermination of Father Calleri's team, Gilberto Pinto Figueiredo was reassigned to the task. The responsibility for building the highway was transferred from the state-level DER-AM to the National Department of Transportation (DNER), which expanded the initial project into a Federal highway, BR-174, between Manaus and Boa Vista. DNER assigned the Brazilian Army the mission of coordinating and conducting the work, even though the forces had no experience in civil construction projects. Thus, the highway work was resumed by the 60th Battalion of Engineering and Construction (60 BEC) of the 20th Corps of Engineering and Construction.

The relations between members of Funai and the Army were tense during the construction period. On the one hand, Funai defined norms of conduct within native territory for all those involved in highway work; on the other hand, the army violated these norms and conducted engineering operations according to its own criteria.

The urgency to bring the construction project to a close intensified the divergence between the two government institutions and undermined the indigenist activities that had been elaborated so far. Their disagreements led to a chain of events that incited the Indians to kill Figueiredo and everyone else at the attraction station in 1974. The 60th Battalion intensified its work and finished the highway, fulfilling the mandates of the Federal and state governments. To ensure traffic flow and guarantee safe passage of passengers against attacks by the Waimiri Atroari along the stretch of the highway that went through indigenous territory, the 60th Battalion installed sentry posts to control the entry and exit of vehicles across the northern and southern boundaries of the reservation.

The Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Reservation was created in 1971. However, the Federal government's plans for developing the Amazon region continued to impinge on their territory. During the 1970s, photographs from the Amazon Radar Project (RADAM) revealed cassiterite deposits lying within their reservation. In the early 1980s, the Paranapanema company expressed interest in exploiting these deposits. With the help of Funai and the National Department of Mineral Production (part of the Ministry of Mines and Energy), the company filed a lawsuit that led to the dissolution of the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Reservation, demoting it to a Temporary Restricted Area for the Attraction and Pacification of the Waimiri Atroari Indians in 1981. This new presidential decree excluded the mineral deposits from the indigenous territory. Later in the 1980s, another massive project impinged on Waimiri Atroari lands, the construction of the Balbina hydroelectric project by Eletronorte, creating a lake that flooded 30,000 hectares of their territory.

Contemporary Waimiri Atroari society

The land where the Waimiri Atroari live is located in the northern part of the state of Amazonas and the southern part of Roraima in the Brazilian Amazon. This region lies to the east of the lower Rio Negro, covering the river basins of the Rios Jauaperi and Camanaú and their tributaries, the Rios Alalaú, Curiaú, Pardo, and Santo Antonio do Abonari. Long ago, the land of the Waimiri Atroari (which they call kinja itxiri) was more extensive, reaching the Rios Urubu, Uatumã, and Anauá.

Census data from the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth estimated that the Waimiri Atroari population was between 2000 and 6000. In the 1970s, Funai made an estimate of 500 to 1000 people. However, all these figures were based on speculation rather than actual census counts. The fact remains that the Waimiri Atroari population decreased during their contact history because of the frontier wars and foreign diseases, falling to 374 people in 1988. In December of 2001, their population had increased to 913, divided into nineteen local groups belonging to three hamlets.

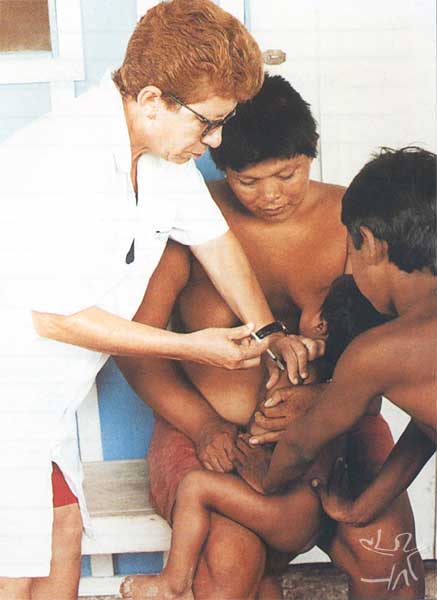

In 1987, a project for mitigating the environmental impact of the Balbina Hydroelectric Dam was proposed and presented to the Waimiri Atroari, Eletronorte, and Funai. The project, known as the Waimiri Atroari Program, planned to deliver services in the areas of health, education, environment, agricultural assistance, border security, documentation, and historical memory. When the interested parties accepted the proposal, an accord was signed between Funai and Eletronorte, the former agreeing to implement the project and the latter to finance it. Under the terms of this arrangement, an area of 2,585,911 hectares of land was demarcated for the Waimiri Atroari reservation, which received permanent legal status in 1989.

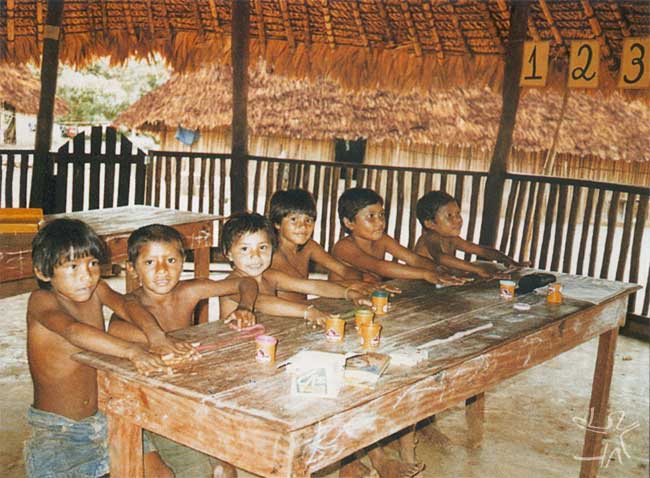

Nowadays, the Waimiri Atroari have access to a culturally distinct school system, in which they themselves design and conduct the educational process, as well as access to medical and dental services. The growth rate averages 5.8% per year. They have sought to manage the new demands spurred by the processes of cultural encounter. They try to utilize various industrialized products to improve their working conditions and to reduce the time spent traveling between distant locales. The enhanced quality of life can be observed in the daily activities of the Kinja, who have more time available to spend on social, economic, and cultural activities. The benefits have also led to an increase in the birth rate, visible in the number of boys to be initiated in the maryba festivals, which are becoming ever more frequent and indispensable to the cultural agenda of the Waimiri Atroari.

Sources of information

- BAINES, Stephen Grant. Anthropology and commerce in Brazilian Amazonian : research with the Waimiri-Atroari banned. Critique of Anthropology, Londres : Sage, v. 11, n. 4, p. 396-401, 1991.

- --------. Censuras e memórias da pacificação Waimiri-Atroari. Brasília : UnB, 1993. (Série Antropologia, 148)

- --------. "É a Funai que sabe" : a Frente de Atração Waimiri-Atroari. Belém : MPEG, 1991. 362 p. (Originalmente Tese de Doutorado defendida em 1988 na UnB).

- --------. Epidemics, the Waimiri-Atroari indians and the politics of demography. Brasília : UnB, 1994. 38 p. (Série Antropologia, 162)

- --------. Imagens de liderança indigena e o Programa Waimiri-Atroari : índios e Usinas Hidrelétricas na Amazônia. Brasília : UnB, 1999. 16 p. (Série Antropologia, 246)

- --------. A política governamental e os Waimiri-Atroari : administrações indigenistas, mineração de estanho e a construção da "autodeterminação" indígena dirigida. Brasília : UnB, 1992. (Série Antropologia, 126) Publicado também na Série Antropologia da UnB n. 152 de 1993 e na Rev. de Antropologia da USP, v. 36, 1993, p. 207-37.

- --------. Política indigenista governamental no território dos Waimiri-Atroari e pesquisa etnográfica. Brasília : UnB, 1997. 12 p. (Série Antropologia, 225)

- -------. Raison politique de l'ignorance ou l'ethnologie interdite chez les Waimiri Atroaris. Recherches Am. au Quebec, Montreal : Soc. de Recherches Amer. au Quebec, v. 22, n. 1, p. 65-79, 1992.

- --------. A resistência Waimiri-Atroari frente ao "indigenismo de resistência". Brasília : UnB, 1996. 15 p. (Série Antropologia, 211)

- --------. O território dos Waimiri-Atroari e o indigenismo empresarial. Brasília : UnB, 1993. (Série Antropologia, 138)

- --------. A usina hidrelétrica de Balbina e o deslocamento compulsório dos Waimiri-Atroari. Brasília : UnB, 1994. 14 p. (Série Antropologia, 166)

- --------. The Waimiri-Atroari and the Paranapanema Company. Critique of Anthropology, Londres : Sage, v. 11, n. 2, p. 143-53, 1991.

- --------. Os Waimiri-Atroari e a invenção social da etnicidade pelo indigenismo empresarial. Anuário Antropológico, Rio de Janeiro : Tempo Brasileiro, n. 94, p. 127-60, 1995. Publicado também na Série Antropologia da UnB n. 179, 1995.

- --------. O xamanismo como história : censuras e memórias da pacificação Waimiri-Atroari. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp, 2002. p. 311-46.

- BELTRÃO, Luiz. Os Waimiri Atroari : terra, gente e luta. In: BELTRÃO, Luiz. O índio um mito brasileiro. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1977. p.255-98.

- CARVALHO, José Porfírio F. de. Poluição do projeto Pitinga na Área Indígena Waimiri Atroari. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 247-8.

- --------. Projeto Waimiri-Atroari - Eletronorte. In: LIMA, Antônio Carlos de Souza; BARROSO-HOFFMANN, Maria (Orgs.). Etnodesenvolvimento e políticas públicas : bases para uma nova política indigenista. Rio de Janeiro : Contra Capa Livraria, 2002. p. 127-31.

- --------. Waimiri-Atroari : agora, a poluição dos rios. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 194-9. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- --------. Waimiri Atroari : a história que ainda não foi contada. Brasília : s.ed., 1982. 154 p.

- CAVALLEIRO, Henrique Santos. Geografia - Itxiri ikaa - Primeiro Livro. Rio de Janeiro : PWA, 1995. 43 p.

- ELETRONORTE. Ambiente, desenvolvimento, comunidades indígenas. Brasília : Eletronorte, 1994. 24 p.

- EMIRI, Loretta; MONSERRAT, Ruth. Waimiri Atroari. In: --------. A conquista da escrita. São Paulo : Iluminuras ; Cuiabá : Opan, 1989. p.139-50.

- ESPÍNOLA, Cláudia Voigt. O sistema médico Waimiri-Atroari : concepções e práticas. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1995. 251 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- LACERDA, Edith M. N. Waimiri-Atroari : observações lingüísticas. Brasília : Eletronorte ; Funai, 1991. 25 p. (Programa Waimiri Atroari, Subprograma de Educação)

- MAZUREK, Roselis Remor de Souza. Kinja txi taka nukwa myrykwase. Chicago : Univers. of Illinois, 2001. (Tese de Doutorado)

- MILLIKEN, William et al. The ethnobotany of the Waimiri Atroari indians of Brazil. Londres : Royal Botanic Gardens, 1992. 155 p.

- MONTE, Paulo Pinto. Etno-história Waimiri-Atroari (1663-1962). São Paulo : PUC, 1992. 167 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- OLIVEIRA, José Aldemir de. Waimiri-Atroari : invasão e fragmentação do território indígena. Travessia, São Paulo : CEM, v. 9, n. 24, p. 39-43, jan./abr. 1996.

- OLIVEIRA, Wagner de. Os Waimiri Atroari. Manaus : Programa Waimiri Atroari, 1999. 14 p.

- PEREIRA, Verenilde Santos; BAINES, Stephen Grant. Funai e Paranapanema tomam conta dos Waimiri-Atroari. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 200-2. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- PROGRAMA WAIMIRI ATROARI. Cólera Ika. Manaus : PWA, 1991. 10 p.

- --------. Ira myry paryry mydy ne? Você conhece minha aldeia? Manaus : PWA, 1992. 14 p.

- --------. Plano de proteção ambiental e vigilância na Área Indígena Waimiri Atroari : relatório de atividades ano 1997. Manaus : PWA, 1998. 70 p.

- --------. Relatório de Atividades 1998. Brasília : Eletronorte, 1999.

- SILVA, Márcio Ferreira da. O parentesco Waimiri-Atroari : algumas observações. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Orgs.). Amazônia : etnologia e história indígena. São Paulo : USP-NHII ; Fapesp, 1993. p. 211-28. (Estudos)

- --------. Romance de primas e primos : uma etnografia do parentesco Waimiri-Atroari. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ-Museu Nacional, 1993. 400 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Sistemas dravidianos na Amazônia : o caso Waimiri-Atroari. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo (Org.). Antropologia do parentesco : estudos ameríndios. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1995. p. 25-60. (Universidade)

- SOUZA-MAZUREK, Roselis Remor de et al. Subsistence hunting among the Waimiri Atroari indians in central Amazonia, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation, Amesterdan : Kluwer Academic Publishers, n.9, p.579-96, 2000.

- THE TRAUMA of contact. Survival: Newsletter, Londres : Survival International, n. 29, p. 8-9, 1991.

- UNIVERSIDADE DO AMAZONAS. Núcleo de Estudos Etnolingüísticos. Tytyosen benry - caderno de matemática. Manaus : UA, 1995. 69 p.

- Nossa história - A'a Ikaa. Vídeo Cor, VHS NTSC, 35 min., s.d. Prod.: Programa Waimiri Atroari