Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau

- Self-denomination

- Jupaú

- Where they are How many

- RO 127 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Tupi-Guarani

...once there was an Indian woman who turned into the moon. Then one day she went, she climbed up a tree, she wanted to stay in the sky... The woman became angry because her boyfriend found another girlfriend. She became angry and said: - Ah I’m not going to stay here anymore; I’m going to live in the sky. In the beginning there was no darkness. A lot of wild animals wandered around here. Then tupangá. Everything changed: wild animals have to sleep, they go hiding into their holes in the early morning. The Indian goes hunting in the woods in the early morning. When it gets dark, then it’s alright to sleep. In the beginning, there was no darkness... This piece of the myth of the creation of the day and night is shared among the Jupaú (better known among the Whites as the Uru-eu-wau-wau) and the Amondawa, groups which consider themselves distinct but both of which are Kawahib, who speak the same language and share ways of life which are similar.

Identification and demography

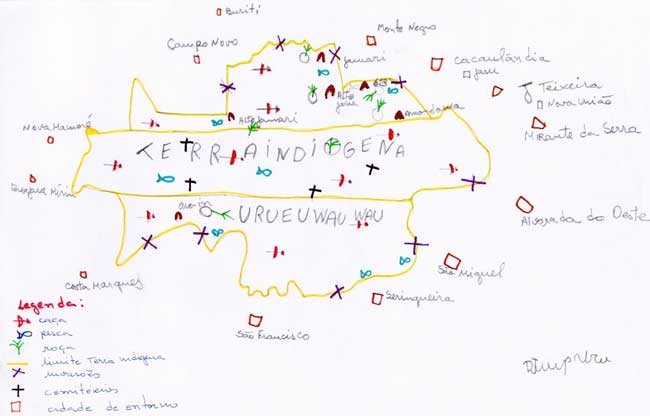

The population of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous land is comprised of various subgroups - the Jupaú, Amondawa and Uru Pa In which are distributed in six villages on the borders of the Indigenous Land, for reasons of protection and security. Besides these groups, there are also isolated Indians such as the Parakua and the Jurureís, as well as two groups whose names are unknown, one in the Southwest (on the mid-Cautário River) and the other in the center of the Indigenous Land (on the Água Branca Stream).

The Jupaú translate their self-designation as “those who use jenipapo". The name "Uru-eu-wau-wau" was given to the Jupaú by the Oro-Uari Indians. There have been many names attributed to the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau: Black-Mouths, Cautários [referring to the name of a river], Sotérios, Red-Head, are all found in the historical literature and related to the geographical space or cultural and linguistic similarities of the Jupaú and Amondawa, or the Kawahib groups in general.

After contact, in the beginning of the 1980s, a significant population decrease occurred among these groups. The population went from 250, in 1981, to 89 in 1993, particularly among the Jupaú people. About 2/3 of them were killed off as a result of conflicts and a series of diseases that struck their villages, principally respiratory infections. In the years after 1993 there was a slight growth in the population, in part due to the demarcation, fiscalization and vigilance in the Indigenous area. The most significant increase occurred among the Amondawa population. In 1995 the population of the Indigenous Land rose to114 people; in 2000, it was 160 people; and in 2002 it was 168 people.

The Amondawa people stand out among the ethnic groups of the Indigenous Land as having the largest population growth, totaling 83 people. This can be explained by the improvement in their socio-economic conditions, since they have a considerable agricultural production, with technical assistance in the village of Trincheira (where they live), allowing them to build up their food security. The four Jupaú villages (Alto Jamari, Jamari, Linha 623 and Alto Jaru) have a total population of 85 people, among whom there is a non-Indian woman married to a Jupaú, an Arara woman married to an Amondawa, three Juma married with Jupaú and one Juma man (the Juma are in the village of Alto Jaru).

Location

Having been declared in permanent possession of the Indians in 1985 and then revoked in 1990 by President José Sarney, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous land was once again homologated by decree by the then President Collor in 1991. The area has a total extent of 1,867,117. 80 hectares and a perimeter of 8,656,153.01 meters. It overlays the National Park of Pacaás Novos, created in 1979.

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land is administered by the National Indian Foundation through the Regional Administration of Porto Velho. It has three Indigenous Posts (PIN), with hired Post heads: the PIN Comandante Ari, PIN Trincheira and PIN Jamari, and – with no decrees – the Indigenous Vigilance Posts (PIV) of Alto Jaru (village of Arimã), Linha 623 (village of Paiajub), the PIV Bananeira and the PIN Oro-win. There is even an unofficial Indigenous Post called São Luiz, where the Oro-win community lives, which is located on the banks of the river of the same name and is attended by the Regional Administration of Guajará Mirim. This Post, however, has no administrative decree providing for a head of the Indigenous Post or for a nurse’s aide, which puts the Indians at a disadvantage in terms of attendance.

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous land includes part of the Pacaás Novos mountain range and the Uopianes mountain range. The first is notable in having the highest point of Rondônia, Tracoá Peak, with 1,230 meters altitude; the second has altitudes no greater than 600 meters. The landscapes are diversified and the geographical relief in places is in the form of hills with or without forest, or in the form of flat plateaus and residual relief (inselbergs), many of them with caverns.

The area contains a rich biological diversity and untouched spaces. It is also the source of the waters of at least 12 hydrographic sub-basins of Rondônia. On top of the hills, it is common to find fields, sparse forest, and other endemic formations, while on the edges one finds open tropical forest and closed forest where there are soils of greater depth.

The rivers are called paraná in the Kawahib language; the streams are called côo-via; the lakes, ipapê-bua. The ciliate forest is called paraná-capura.

History of contact

From the anthropological information provided by Nimuendajú, the State of Rondônia had a reasonable number of “forest-dwellers” from various ethnic groups who inhabited the region. Besides the traditional peoples, the occupation of Rondônia by non-Indians was always motivated by economic interests. The first flux of non-Indians occurred in the 18th Century with the search for indigenous slave labor. The second, in the 19th Century, was motivated by the search for gold. At the end of the 19th Century, the rubber boom began, which lasted until the bust in 1910-1920. After the Second World War, there was a resurgence of the rubber boom along with mineral exploitation, especially of cassiterite and gold in Amazonia, attracting a new flow of migrants which occupied the region, provoking conflicts with scores of indigenous peoples. Thousands of Indians died in combats and/or epidemics and had their lands invaded.

After the 1940s, the first government colonization projects began. In the beginning of the 60s, construction began on highway BR 364, which "ripped" the state from Southeast to Northwest, and was executed by the Polonoroeste Program (Integrated Development Program for the Northwest of Brazil) and financed by the World Bank. Following the route of the highway, in the early 1970s, large government colonization projects brought thousands of agriculturalists from the south and southeast of Brazil, which in effect simply relocated to the region the political impasse around the issue of agrarian reform.

In the specific case of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, although there are reports since 1909 on the indigenous occupation of the region, including records of conflicts and location of villages, official records were only made after 1976, when three malocas were located between the headwaters of the Rio Branco and the Cautário and Sotério, near the Pacaás Novos mountain range, and one near the Souza Coutinho stream, at Mutum rapids.

The area of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau occupation went from the valleys of the Madeira (to the north), Machado (to the east), Guaporé (to the south) rivers and on to the Mamoré (to the west), according to available historical records and the oral reports of the Indians. Since at least the beginning of the 20th Century, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau have struggled against the fronts of expansion that invaded the region.

Long before official contact of these groups, the first concrete proposal for delimitation of the indigenous reserve was made in 1946, when the government of the Territory of Rondônia was informed of indigenous occupation of the entire basin of the Jamari River and the basin of the Floresta River up to the Pacaás Novos mountain range. According to the document prepared at that time, the decision of November 26, 1946, was favorable. “In 1946, after the massacre caused by Mr.Manoel Lucindo of the villages of the Oro-Towati and the various counter-attacks on the part of the Indians, the SPI [Indian Protection Service] decided to interdict the area included in the São Luiz Rubber Camp, and this act was communicated through official letters 30/64, 32/64, 33/64, to Mr. Manoel Lucindo, to the Government of the Territory of Rondônia and to the Credit Bank of Amazonas”.

Various interdictions in the area were proclaimed until, on March 24, 1984, through Decree 176/E, the President of the Funai established a work group to study the identification and definition of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Urupa-In indigenous area. On July 9, 1985, the area was declared to be the permanent possession of the Indians, through decree 91.416. In 1990, President Sarney revoked the decree but, on October 29, 1991, President Fernando Collor homologated the administrative demarcation of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous area.

The Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau were contacted by the Funai on March 10, 1981, in Alta Lídia, today called Comandante Ary. On the occasion 250 people were contacted. In 1984 the Funai located three villages; but in 1986 there were in all a total of eight villages. At that time, the Comandante Ary post had already been visited by more than 150 Indians, and the Funai calculated that there were approximately 500 Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau.

The Jupaú state that there are still three other groups who have not been contacted, who live in the region of the Muqui River, Cautário and S. João do Branco. The report made at the time mentioned the existence of several villages still without contact, in which it was calculated that there were around 1000 to 1200 isolated Indians in the Indigenous area. Research shows that the group identified as Mamõa worked without pay for the rubber-gatherers; the Amondawa were surrounded by invaders and requested the intervention of the Funai, who didn’t know where their villages were located; A Jupaú woman identified as Kanindé commented that her mother and sister had been captured by the rubber-boss Alfredo. Their descendants even today tell how their mother died and sister continued in the power of the invader, and that she would like to go back and live in the village, even though she was not raised among the Jupaú.

The chief of the Ajudância [Assistance] of Guajará Mirim, of the Funai, concluded in his report dated May 3rd, 1988 that the indigenous reserve should not be created in the place that the Indians occupied, for this would be harmful to the rubber-bosses and rubber-gatherers. At that time, the Incra [National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform] was already creating the Costa Marques Land-titling Project, with a clear position in favor of the non-Indians. However, the report alerted to the need for the Funai to send a backwoodsman to the area to make contact before the rubber-bosses did.

In 1980 11 huts and gardens were located on the Jamari River and near the fields of Comandante Ary (Alta Lídia). Camps were also found on the left bank of the Urupá, near BR 429, and in 1984 a village on the Urupá and another in São Miguel; besides the camps on Tracoá hill, on the Jamari/Candeias divide, on the Ricardo Franco, Muqui, Igarapé Pombal, Jarú, Cautário, São Miguel, Ouro Preto, Água Branca and in the Pareci/Pacaás Novos mountain range (three settlements with various malocas inside the Pacaás Novos Park, 7 kilometers distant from one another).

Invasions

In the history of the Indigenous Land, there have occurred successive invasions, both by lumbermen and rubber-bosses, and by peasants in search of lands. The invasions intensified after the 1980s and persist until today. The low level of fiscalization by the responsible public agencies and the isolation of the area have contributed much to worsen the situation. There are frequent denunciations, despite the government of Rondônia having signed an agreement to fiscalize the invasions on the Indigenous Lands. One recent example is what occurred in April, 2003 with the invasion of 5,000 non-indigenous people who called themselves the “League of Poor Peasants”. Their removal took place weeks later and involved a joint operation of various public agencies — Federal Police, the Funai, the Ibama, the Incra, the Forest Police Battalion and the Secretary of Public Security of the State of Rondônia — and the NGO Kanindé.

In the second half of the 1980s, after the paving of BR-364 the commercialization of lumber with the south of the country intensified. The selective exploitation of good quality timber in the State of Rondônia made the stock of these species diminish considerably on the private properties, becoming available only at long distances from the beneficiary industries. With that, the stealing of lumber on indigenous lands, principally the good quality lumber (mahogany and cherry), also became more intense. Various cities with scores of lumber mills are installed on the outskirts of the Indigenous land. It is estimated that 90% of the mahogany and 80% of the cherry wood that are brought to lumber industries of Rondônia come from Indigenous Lands or Conservation Units.

Adding to the pressure of the lumber commerce, the population in the area around the Conservation Units is growing. As an electoral strategy, many municipalities were created in the State, part of them with no infra-structure and small population, and no power to raise money for their very survival. In 1991 the State of Rondônia had only 40 municipalities, today it has 52. The territorial area of several municipalities that have been created overlap by more than 50% inside the Indigenous Lands. In view of this reality, the tendency is for there to be ever greater anthropic pressure on the Indigenous Lands.

The Amondawa and Jupaú have been historically hostile to the economic colonizing fronts since the beginning of the 20th Century, living in conflict with the rubber-bosses and gold-panners. Over the last few decades, the struggle has been against the invasion by cattle-ranchers, agriculturalists, prospectors, and against the actions of the lumbermen who have stolen, over one decade, more than 500,000 cubic meters of lumber, mainly of good quality.

Over the last ten years, a large number of fiscalizing actions have been undertaken on the indigenous land and in the national park. The actions that have been successful, have led to the opening of scores of police inquiries, with the confiscation of nearly a hundred vehicles, including trucks and tractors. Most of these vehicles were returned to the infractors, in accordance with the legislation that leaves the accused as loyal depositary, while the process is being tried in court. But often the Indians have demonstrated their revolt against the decision of the judges and burned the vehicles so that they wouldn’t be returned to their owners. Many of these infractors have nevertheless returned to the area and continue stealing lumber.

The Disputed Burareiro Area

In the most recent history of the Jupaú, the Floresta River was the stage for a major conflict between Indians and non-Indians. Even after the Funai had notified the Incra that the region was interdicted for the Indians, the Incra issued 122 definitive titles to agriculturalists inside the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous area, creating a problem that still hasn’t been solved, with losses for the Indians, for the area has suffered from the plundering of its resources.

At the end of the ‘70s, the Geographical Department of the Brazilian Army was contracted by the Funai, to undertake the demarcation of the indigenous area, due to the complexity of the conflicts in the region and the size of the land to be demarcated. The Army in turn contracted a company to undertake the final work of physical demarcation. After several months had passed since the demarcation, the Funai still had not checked the limits of the area. When the backwoodsmen tried to find the demarcation markers and borderlines, they couldn’t. The demarcation borderline clearings had not been correctly done and the few markers that had been put in place had been ripped out by the invaders.

On November 11, 1980, the Incra illegally issued 113 titles in the southern part of the Burareiro Project, located within the Indigenous Land. In 1985, the MIRAD-INCRA recognized that most of the people who received titles were not living on the lots, that the occupation was precarious due to the lack of access roads and that the deforestation in the region had barely begun (Altamir Wolmann, MIRAD/INCRA, 04.06.85). In the same year, the limits of the Indigenous Land were finally defined by Presidential decree and it was expected that the INCRA would resettle the people with titles in another region, thus respecting the indigenous land. But that did not happen.

In the Cattle-ranching and Forestry Plan for Rondônia (PLANAFLORO) and in successive Aid Memoranda of World Bank missions in Rondônia, the grave situation of Burareiro was noted, but at the conclusion of the execution of this plan, no emphasis was given in the sense of finding a solution to this situation. The question was considered a legal problem to be settled only by the Funai. The agency, after much delay, in 1994 initiated a legal process against the Incra to nullify the titles on the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous land. The Court decision in 1996 was unfavorable to the Indians, for the Court interpreted that that the process initiated by the Funai should not be against the Incra, but rather against each of the 122 owners of Definitive Titles. Since most of these titles had already been sold to third-parties, this would this would result in a large number of legal actions to be taken against the title-holders, which would be unviable in the short and long run.

On April 27, 1995, in an inter-institutional meeting of the state government, a proposal was made that the remaining area (an area of 39,000 hectares proposal to be diminished) of the Karipuna Indigenous Land be used to settle, besides the 184 local invaders, the invaders of Burareiro and the 40 invaders of the Mequéns Indigenous Land. The Funai complied with the proposal, but the Incra and the State did not remove the invaders from the indigenous lands. Consequently, the invasions remained and new ones occurred in the excluded area of the Karipuna.

The court decision in 1996, regarding Burareiro, is being used in a distorted way by businessmen and politicians of the municipalities of Ariquemes and Monte Negro who are acting unfairly to stimulate invasion. In 2001, the Funai, Federal Police and Public Ministry, with support from the Jupaú indigenous association and the Kanindé association undertook the de-occupation of the northern side of the indigenous land, in which scores of invaders were taken to the central Penitentiary in Porto Velho. The representatives of two associations of invaders were indicted in legal processes. For the first time, the imprisonment of professional invaders of indigenous lands in Rondônia was obtained.

Social organization

Like the other Kawahib peoples, the Jupaú and Amondawa are divided into kin groups, each with a chief, organized in two moieties: the Curassow and the Macaw.

Before contact, they were highly mobile, there being fixed settlements at certain times of the year and temporary camps or tapiris, spread throughout the whole area of occupation.

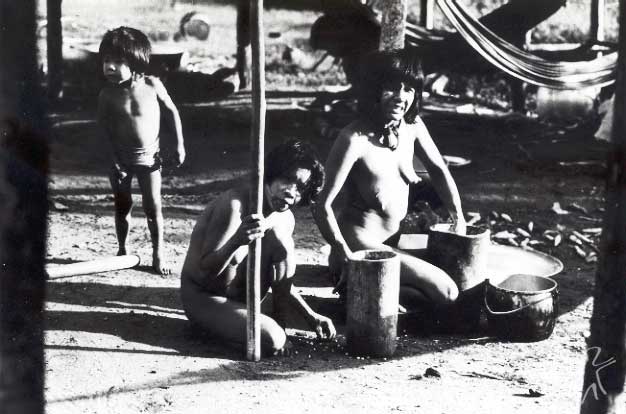

The villages were built in small clearings opened in the woods. In their gardens they planted corn, sweet cassava, sweet potato, yams and cotton. They produced manioc flour and a fermented beverage of sweet cassava. They did not use tobacco and, according to the records, one non-Indian who lived with them in the 1940s was able to get tobacco from the rubber-gatherers (Costa, 1981). Before contact, they lived in rectangular malocas, with very high sloping roofs, and doors on both sides. Presently, besides the malocas (which are few in number), they live in wooden houses with roofs of sheets of asbestos, a practice which was introduced by the Funai.

The Jupaú often complain that these houses are very hot, preferring to stay in the malocas during the day, in the villages that still have them. They make small thatch traps, to catch game, and build thatch shelters, when they go on long trips within the indigenous land.

Marriage and Kinship

Marriages are traditionally polygamous and are arranged between the two moieties, such that the Curassow only marry with the Macaw. Marriages are arranged between cross cousins: the young man marries his mother’s brother’s daughter. In the last few years, due to the scarcity of women and the influence of contact with non-Indians, marital relations have become monogamous, there even being cases of polyandry. Due to this solution, the men have gone to live with the women upon marrying.

When a child is born, it is already promised in marriage. With the development of their breasts, the girls already have permission to have boyfriends. Actually, at times there is a certain resistance in accepting the promised husband, which leads to conflict in the family group.

People of both groups change names at each birth of a member of the nuclear family. When a boy is born, he receives the name of the father when he was a baby; as he grows older, he takes on the names that his father had.

The dead and spirits

The Jupaú bury their dead inside their malocas, together with all of their belongings. When for some reason they have to move, they continue to come back to visit and clean the place where they buried their dead, or they remove and take the bones to the new dwelling place.

The graves are circular and the deceased is buried in a seated position with all of his/her belongings, including with an eagle feather crown on top of his chest, in order to protect him in the world of the spirits.

The Jupaú believe that there exist various spirits in the forest, to which they give various names and tell stories about their deeds and how these influence the life of the community. One of these spirits is the Anhangá, which has the appearance of a large bat and carries people away, sucking all of their blood.They say that Djurip’s (a Jupaú) grandfather’s grandson was carried off by the Anhangá. His grandfather went to look for the child, and when he heard the noise of the specter, which was near a log; he tried to cut it with a machete, but he wasn’t able to for the specter disappeared. He saw the child being carried under its wings. When he tried to get it, the specter went behind the log and disappeared with the child. According to Moram Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, this occurred at the headwaters of the Jamari River.

Myths

Below is a small sample of the rich mythology of these two Kawahib peoples.

The appearance of night

The Bacurau [night-bird] told the jaguar to open its mouth, to see the jaguar’s tooth. The jaguar opened its mouth, the bacurau shat in it, and the jaguar vomited and almost died. The bacurau flew away; then the jaguar’s friend appeared and said: "What happened?". The jaguar told his friend. His friend went in the maloca and burned all the species of corn, while the jaguar continued vomiting. When he came to the black corn to burn, night appeared. The jaguar didn’t know what to do, he waited for the day to appear; he tried to light the fire but it wouldn’t light. The night lasted for three days, and after that day and night began to alternate always one after the other. The jaguar, who had vomited so much he died, came back to life again. (narrated by Djurip Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau).

The use of fire in the story of the frog and the snake

During the flood, the frog and the snake had no axe to make fire and warm themselves. They decided to cross the river to the other side, with a hot coal they had found and that they carried on their ribs, but they couldn’t get back to the riverbank.

The frog got the coal and, when he got to mid-river, he decided to look for a narrow part of the river. The stubborn frog decided to cross the river in that place with the coal, jumping long distances in such a way that he could get to the other side and make a fire on the other side, with which he warmed himself during the cold period. The snake, as it didn’t know how to jump, stayed on the other side, in the cold (narrated by Djurip and Mora Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau).

Adornments and festivals

The Jupaú and Amondawa are accustomed to singing at night to scare away their enemies with their cries or remember their deceased loved ones.

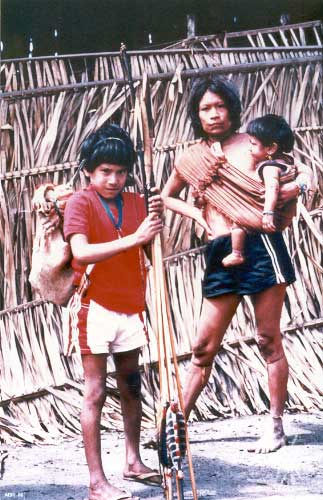

They also dance in their various festivals. The corn festival is called Ipuã and another well-known festival is the Yreruá. In this, the men play bamboo flutes, carrying their arrows, where the bows are held taut as if they were about to shoot the arrows. The women, at a certain moment during the festival, dance clinging to their arms. At certain moments, they shout which traditionally has a warrior connotation.

During the dance, the "Chief of the Festival" stands in the middle of the circle, playing the large flute (Yrerua), and leading the dance rhythm by stamping his feet on the ground. The men use several rolled-up vines on the hips and wider vines at the height of the stomach, where they hold their machetes.

To celebrate first menstruation, the festival of the young girl is held.

The girl has to stay inside the maloca for a month and a half during the period of castanha collecting. She cannot bathe and babaçu oil is rubbed over all her body. On the second menstruation, she tells her mother, who communicates to the father, who spreads the news throughout the village. She leaves her hammock and is bathed by her aunt, who removes all of the oil from her body.

The castanhas are left out in the open for the men to break at the end of the afternoon. At five in the morning, the father gets up singing and announcing that the day of marriage is getting close. The father, the uncle, the brothers, the husband and betrothed girl go to the river, where they get water to cook the castanha. The others prepare their arrows and body-paint. Later, the women, together with the girl, cook the castanhas.

The girl receives various presents to decorate herself (jaguar tooth collar, bracelets and cabybara tooth collar). The husband receives presents of headdresses, arrows and collars of wildcat and otter teeth. The presents cannot be given again to others. The girl has to take a bath every day and even stay out in the rain to take off the smell of the babaçu oil.

Material culture

On ritual occasions, the Indians paint their bodies with urucum [red dye], and for war they paint their chests with blue-black jenipapo in the shape of an "X", which looks like a bird with open wings.

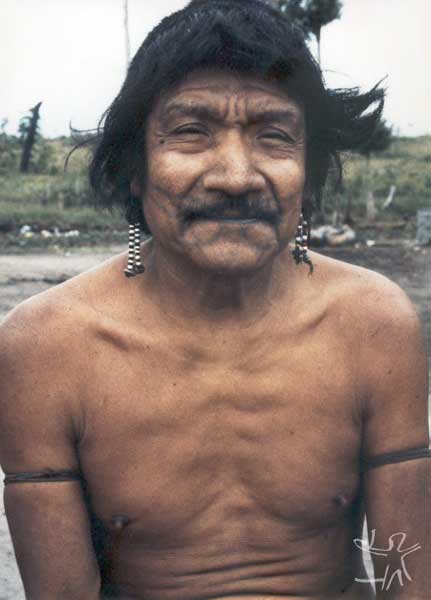

They tattoo the face, with a line from the mouth to the ear and around the lips. Perhaps for that reason they were known by the name of “Black-Mouth". Besides tattooing the face, the men tattoo a fish on the left arm, made with a leaf of the forest. This tattoo is made during the ritual of transforming the boy into a warrior, when the boy is approximately 13 years old.

The women make tattoos around the mouth in the shape of a circle, which they usually say represents a large snake. The facial tattoo of the men, like that of the women, was traditionally done during the marriage ritual. However, with so many transformations that the Jupaú and Amondawa have suffered, the men have stopped tattooing themselves. The women still do, for they believe that in this way they are protecting their husbands during the hunt.

The headdresses and arrows are made by the men with parrot, macaw, and eagle feathers, being used by the men (adults and children). Some eagle feather crowns are made to be used when the men die, at which time they are placed on top of the body of the deceased, and are used during festivals only for the feathers to stay beautiful.

The headdress is considered as a gift to the spirits in exchange for protection. The eagle feather is considered a protector because the eagle is capable of disappearing quickly and is difficult to be observed in the forest. These headdresses cannot be sold nor given away.

The women are accustomed to using capybara tooth collars and the men collars of boar teeth. The women also make collars and rings out of tucumã coconuts and teeth of other animals. These days they also utilize in some cases the lids of medicine bottles, buttons, and other decorations on the collars.

Traditionally, they made earthen pots and baskets to carry game, gather fruit and honey in the forest.

Productive activities

Hunting is a male activity and occurs near the villages, on frequently-used trails, in claypits, at a distance of approximately 3 to 5 kilometers. Groups are also formed for hunting expeditions in more distant places.

In diverse points of the forest there are places where the animals and birds go to dig up and lick the soil to extract the salt that exists in larger concentrations. The Amazonian people call these places claypits or suckers and the Indians call them Itiwawa. In the time of the dry season (Kuaripé) it is easier to find game than in the time of the rains for various reasons: it is the fruit season when the streams are lower and without the inconvenience of the rains. The game is divided amongst all members of the community.

Inventory of the techniques of hunting:

- They make traps (tukai) with babaçu thatch mainly to catch the partridge (various kinds) near the villages, in places where fruits are dropping and in the vicinity of claypits.

- They imitate the sound of the animals to attract them (tapir, peccary), and in some cases, they imitate the young of the species (deer and peccary).

- Tracking is a technique which consists of walking, following peccary or tapir tracks for hours. When the animal has been hit and is bleeding, the Indians follow the trail of blood drops on the forest floor.

- The bow and arrow were the most important hunting and war instruments of the Jupaú, but today they use shotguns of various calibers. The old men, however, continue to use bow and arrow. Different types of arrows are used: Uywa – with a bamboo point to bring down larger size animals; Miarakanga – jaguar bone tip mainly for birds and occasionally for fish; Um'ywa - peach-palm tip for hunting fish.

- The use of the Tikyguywa on the arrowpoint is another technique, that causes bleeding in the animals hunted.

Fishing is an activity that is realized both by the men and the women. The men use bow and arrow, harpoon and threshing nets when fishing. The time of greater abundance of fish is the dry season, when the rivers are lower. Even with the introduction of new techniques, traditional fishing is still done with bow and arrow. The appropriate arrow has a peach-palm tip or jaguar bone. The use of "timbó" (a method which involves the poisoning of the fish) is quite frequent, principally at times of the year when fishing becomes difficult.

There is a selection of the fish that can be eaten and smoked over the grill, or cooked in the pot, or even rolled up in pacova leaves and placed directly in the fire (mpoquiga). They make a mixture (pirakuia) pounding the smoked meat of the fish in the mortar. They are accustomed to taking out and storing the fat of the dogfish to eat with manioc flour.

Their favorite fish was the jatuarana (piawuhua), which disappeared from the Jamari River after the construction of the Samuel hydroelectric dam. The fish Cuiucuiu and Jandia, on the other hand, appeared after the construction of this hydroelectric.

Agriculture

The whole family is involved in subsistence activities. During the year, agricultural activities are intercalated with extractivist activities, hunting, fishing and vigilance of the borders of the Indigenous Land.

They cultivate manioc and sweet manioc. Sweet manioc can be eaten roasted, or, after being roasted, transformed into an unfermented porridge. They also produced manioc flour by grinding the manioc, which later was put on a woven mat under the sun for several days to dry and later, to be eaten. But, presently, the stages in making of manioc cereal are the following: scraping the shells off the roots, using knives, machetes, grating with the manual grater; maceration and fermentation; a mixture made in a wooden trough; squeezing, done in wooden presses; toasting is done on metal pans and heated with firewood. It is an activity that is done by the men and women. After toasting, it is put in bags for internal consumption and the surplus is sold with the support of the Funai. They also produce corn flour (watikuia) in the mortar; they consume green or dry corn; they also make porridge (Kaminha), which is consumed with no fermentation.

They know several varieties of yams (cara), which are planted in new gardens and in the trunks of fallen trees. In part of the garden or to the side of the malocas, they plant a variety of sweet potato (ytyga). They even cultivate a variety of taioba (mabaé), and consume its cooked leaves with meat and manioc flour which they call mbotawa. Near the dwellings they also plant a variety of cotton (amanjiju) and urucum [vegetal dye]. Cotton is used in the making of string. The urucum is used for body painting and as an insect repellent.

The papaya is a plant cultivated since the time of the ancestors, often it sprouts in old gardens that are re-utilized.

The space utilized for the garden is a place near the villages, chosen in the forest to be cut down and burnt in the system of slash and burn, or "coivara". This technique is still what prevails up to the present day among the Indians and also among the regional population, although today they utilize metal cutting tools.

Before contact they used the stone axe as a tool for cutting trees, which was really difficult in the task of cutting down the forest to make a garden. They would also do the cutting and burning in the dry season. This type of forest management is called “pioneer agriculture".

After the planting and harvesting of the garden, it is abandoned and left to fallow, forming low forest, which can be re-utilized for a garden several years later. The work of cutting the garden is done by the men. Planting, weeding, and harvesting are done by the whole community of the village.

The Diet

It is up to the men to hunt, clean the animal, build the roasting platform(in the case of larger sized animals) and make the fire. The women prepare the other types of food, fish and take care of the children, which are treated with affection by their parents.

Meat is their principal source of protein and is abundant in the Indigenous Land. There is a rigorous selection in the consumption of the animals following Kawahib tradition.

In preparing the animal that has been killed, the skin is not removed and placed in the fire to singe the fur. The meat is roasted (mokaen) on roasting platforms [moquéns], thus staying conserved for several days if placed in the heat of the fire and wrapped in straw and baskets to avoid blowfly eggs from being deposited in the meat.

When they make toasted manioc flour (mbiarakuia), they pound the roasted meat of various animals in the mortar. Tapir fat is extracted and stored for consumption with manioc flour. When they kill a tapir with fetus, they eat the fetus generally roasted in the pacova leaf.

Besides the animals mentioned above, their diet is enriched by the consumption of honey and several insects.

The gathering of fruits to be consumed in natura is an activity that is highly appreciated and complements the diet. The Indigenous Land is rich in fruit trees, and in this entry we discuss those which are especially utilized by the Indians.

The Jupaú and Amondawa have various food taboos, among which are:

- The parents of a newborn cannot consume hot food, otherwise the child’s hair will fall out and it will tremble;

- Red deer: they consider it like people. If it is eaten, the person gets dizzy spells and will slowly die;

- Monkey: makes the child cry and not sleep;

- Jacu: same situation as the red deer;

- Jacamim: if the person has two small children, they will cry all the time;

- Curimba and Urumará: produce itching on the body;

- Paca: produces black spots on the body.

Both groups have the custom of raising birds and animals, which are utilized by the families as raw material for their production of artwork and as pets for the children. Macaws and harpy eagles are raised for their feathers which are used for arrows and adornments.

Other village pets, which are raised above all as playmates for the children are : chicken partridge (Namburawa); Tona partridge (Nambuteua); Jacamim (Gwyryao); Curassow (Mutun'a); Saracura (Arakuria); Parakeet (Kykykyia); Curica (Karainha); Parrot (Airuia Airuua); young peccary (Taitetua); young wild pig (taiahu).

Note on the sources

This entry on the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Amondawa was prepared on the basis of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Ethno-environmental Assessment, undertaken by the NGO Kanindé in partnership with the Uru-eu-wau-wau Indigenous Association and the Funai, with the support of the Ministry of the Environment, and under the supervision of Ivaneide Bandeira Cardozo.

This assessment functions as a general mapping of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous area, taking into account both sociological ( anthropological and legal), as well as ecological factors, considering that exhaustive research was done on the physical dynamics of the region. The information contained in this entry are highly reliable given that the Kanindé maintains an ongoing dialogue with the indigenous people of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau area, besides having done extensive fieldwork, with the help of a highly qualified technical team. Possible imprecisions that might appear in some of the data, particularly with regard to cultural aspects, are in large part due to the recent contact of these peoples, who today are going through many transformations, it being difficult therefore to determine with precision in what state several institutions are found.

Besides the recent work of the Kanindé, there is the Master’s thesis by Mauro Leonel Jr., which was defended in 1988 under the supervision of Professor Carmem Junqueira and later published as a book (in 1995). The goal of this study was to present an analysis of the problems faced by the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau in light of historical and contemporary facts, principally connected to invasions of lands by extractivist industries ( lumber, mining and rubber), to the significant loss of land these people had suffered and to networks of social relations. By the same author, there is an article, "The removal of the boundaries [‘dis-marcation’] of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau lands", published in Povos indígenas no Brasil, 1987-1990 volujme by the former CEDI (which gave rise to the ISA), in which he narrates – from the legal point of view of decrees and homologations – the problems that the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land has gone through, from the time of its creation, up to the measures taken by the Sarney government to revoke the homologation.

Sources of information

- CARDOSO, Maria Lúcia de M. Parecer Antropológico sobre os limites territoriais da área indígena urueu-wau-wau. Porto Velho: Secretaria de Estado de Agricultura de Rondônia e Fundação Nacional do Indio, 1989 (in mimeo).

- LEÃO, Maria Auxiliadora Cruz de Sá et al. Relatório de identificação da TI Uru-eu-wau-wau. Brasília : Funai, 1985. 59 p.

- LEONEL JÚNIOR, Mauro de Mello. A "desmarcação" das terras Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 418-22. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- --------. Etnodicéia Urueuauau : o endocanibalismo e os índios no centro de Rondônia; o direito a diferença e a preservação ambiental. São Paulo : PUC-SP, 1988. 284 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Etnodicéia Uru-eu-au-au : o endocolonialismo e os índios no centro de Rondônia, o direito a diferença e a preservação ambiental. São Paulo : Edusp ; Iamá ; Fapesp, 1995. 224 p.

- --------. Onde se esconder? Carta, Brasília : Gab. Sen. Darcy Ribeiro, n. 9, p. 107-12, 1993.

- NASCIMENTO, Eloiza Elena della Justina et al (orgs.). Diagnóstico etnoambiental Uru-eu-wau-wau. Porto Velho : Kanindé, 2002. 483 p.

- PAIVA, José Osvaldo de. O silêncio da escola e os Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau do alto Jamari. São Paulo : USP, 2000. 153 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PEASE, Helen; BETTS, LaVera. Anotações sobre a língua uru-eu-wau-wau. Brasília : SIL, 1991. 55 p. (Arquivo Lingüístico)

- SAMPAIO, Wany Bernadete de Araújo. Estudo comparativo sincrônico entre o Parintintin (Tenharim) e o Uru-eu-wau-wau (Amondawa) : contribuições para uma revisão na classificação das línguas tupi-kawahib. Campinas : Unicamp, 1997. 94 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SIMONIAN, Lígia Terezinha Lopes. Direitos e controle territorial em áreas indígenas amazônidas : São Marcos (RR), Urueu-Wau-Wau (RO) e Mãe Maria (PA). In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria (Orgs.). Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p.65-82.

- --------. "This bloodshed must stop" : land claims on the Guarita and Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau reservations, Brazil. Nova York : City University of New York, 1993. 530 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Os Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau e os Amundáwa no início dos anos noventa. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 423-25. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- Na trilha dos Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau. Dir.: Adrian Cowell. Vídeo Cor, 50 min., 1990. Prod.: Morrow Carter; UCG.

Videos