Tupari

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- RO 607 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Tupari

In their initial contacts with non-Indians during the first decades of the 20th century, the Tupari called the new arrivals Tarüpa, ‘bad spirits,’ due to the diseases and other adversities they brought. Like other indigenous peoples of Rondônia, the Tupari’s history of contact was primarily marked by their exploitation and the expropriation of their lands by rubber bosses, and after the 1980s by loggers and mineral prospectors. Over recent years the Tupari have striven to reverse this situation and, working alongside other peoples of the region, are now fighting to prevent the installation of hydroelectric dams on the Branco river.

Location and population

According to data from the NGO Kanindé (2005), there are 329 Tupari in the Rio Branco Indigenous Territory (IT), an area also occupied by the Makurap, Arikapu, Kanoê, Aikanã, Aruá and Djeoromitxi. The IT was ratified in 1986 (Dec. 93.074) with 236,137ha, in the municipality of Costa Marques (RO). Within this IT, the Tupari are distributed among the following villages:

| Village | Men | Women | Total |

| Serrinha | 29 | 26 | 55 |

| Trindade | 23 | 14 | 37 |

| Nazaré 11 | 16 | 27 | 53 |

| Colorado | 29 | 21 | 50 |

| Encrenca | 14 | 19 | 33 |

| Cajuí 09 | 12 | 21 | 33 |

| Estaleiro | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Morro Pelado | 20 | 25 | 45 |

| Manduca | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Castilho | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Palhal 21 | 15 | 36 | 51 |

| Bom Jesus | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| São Luis | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 164 | 165 | 382 |

There are also 49 Tupari, divided into seven families (FUNAI 2005), in the Rio Guaporé IT, also home to the people from the Wajuru, Aikanã, Aruá, Kanoê, Wari, Makurap, Mequém, Arikapu and Djeoromitxi groups. This territory was ratified in 1996 with 115,788ha, in the municipality of Guarajá Mirim (RO).

Contact history

Some estimates suggest that there were around 3,000 Tupari at the start of the 20th century. The ethnologist Franz Caspar estimated that they had seen white people for the first time in the 1920s. Thereafter, they had intermittent contact with rubber tappers and other non-Indians. The first ethnologist to visit them was Snethlage, in 1934, when he encountered just 250 individuals. Caspar, in 1948, recorded 200 people and on his return in 1955 (months after a measles epidemic) just 66.

In 1948, when Caspar spent several months among the Tupari, he recorded the following account from Waitó, the village’s foremost shaman and political leader:

When I was a child, the Tupari did not know that white and black men lived in the west. Only ourselves, the Tupari, lived in this region, and, surrounding us, the neighbouring tribes. We were all good friends. Our fathers only fought ferociously with the wild Hamno. Our best friends were the Makurap, called Tamo in our language. We visited them regularly, though the way was extremely difficult since the sun scorched our heads all day as we crossed the big open savannahs. (...). One day, our friends told us that strange men had arrived via the river. Some had white skin, the others black. They didn't go around naked like ourselves, but wore trousers and shirts. They navigated the rivers in large boats that sent out a monstrous smoke. They didn’t hunt with bows and arrows, they shot game with a tube that made a strong blast, firing hard stones into the animal’s body.

These men spoke a language nobody understood. They soon reached the Makurap malocas. They weren’t bad: on the contrary, they gave the Makurap may necklaces, mirrors, knives and axes. Afterwards they built their maloca next to the river and went in search of the trees we call herub whose sap we use to make balls with which to play games. But the white men didn’t make small balls with the herub sap, but large balls, which they carried downriver in their boats. They also felled many trees and planted some maize, banana, manioc, rice too and many other things. They recruited the Makurap and gave them more knives and axes, as well as trousers and shirts, hammocks and mosquito nets. In exchange, they asked the Makurap to help them fell the trees and clear trails through the forest.

We saw the axes and knives that the Makurap received from the strangers. They were much harder than the stone axes with which we worked and they didn’t break when using them. The knives were also much better than ours made from bamboo and can stalks, which we used to cut meat and trim the feathers for our arrows. We wanted these axes and knives too, but we were afraid of the strangers. The elders didn’t call them people but ‘Tarüpa', bad spirits, carriers of diseases that kill people. We therefore called the strangers Tarüpa and still do so today. We know that they’re not bad spirits, though they have brought sickness among us.

When we first brought the news home about the strangers, the women cried and said: the Tarüpa will come here to kill us and our children. We immediately went back to our Makurap friends. They showed us more of the presents given by the strangers. We asked for some of the axes and they gave us some used ones they didn’t need any longer since they continually received new and better tools from the whites.

However, we saw that many Makurap were coughing and dying. The coughing was brought by the motor boats from the villages of the strangers. All the Makurap coughed and many, many of them died. The Tarüpa also went to visit the Jabuti, Wayoró, Aruá and Arikapu and took them to work in their rubber plantations and forests. These groups also received knives, shirts and trousers. But they also began to cough, develop headaches and fever. Most of the died. Few survived. Finally the strangers reached even here. Two white men arrived at our malocas. They were called Cravo and Awitchi. They were brought by Bipey, the Makurap leader. Many Arikapu were carrying their baggage. We had not yet seen a Tarüpa and we were really startled. We grabbed our bows and arrows and the women fled with the children into the forest, or hid in the maloca, yelling and crying. However, Bipey told us that the whites wanted to be our friends and had brought us a lot of presents. The Tarüpa distributed salt, sugar and many other things and Bipey told us that we should go to work for them in the seringal (rubber extraction area). That way we would receive axes and machetes. I was unable to go with them because a small cayman had bitten me on the arm – look, I still have the scar. But many went with the Tarüpa to chop down forest. They’d been working there for a few days when a tree fell on a white man and killed him.

The Tupari became frightened and ran away. Many brought axes back home. These were the first good axes we had. When Cravo visited us, he coughed a lot and his nose ran with mucus. Our men, women and children also started to cough, their noses ran and they had headaches and sore chest. Many Tupari died, including many leaders and shamans. So we became fearful and no longer wanted to work with the whites. But we wanted more axes and knives. By the time I had married and my daughter Maéroka had already been born, another Tarüpa appeared here, Toto Alemão (‘Doc German’ was Dr. E. Heinrich Snethlage). He came with many Jabuti, Wayoró and Arikapu men and another three Tarüpa. One of them was black and called. Toto Alemão brought many presents: knives, axes, combs, necklaces, clothing and many other things. He was a very good man, very tall, bigger than you and all the others here. The black man Nicolau laughed and danced a lot with our women and gave us glass beads. However, Toto Alemão was ill. He coughed a lot. Our women began to cough again and many died. When he left, we accompanied him to the whites’ hut. We worked there and were given more axes and knives, as well as trousers and shirts. Later we visited the whites again. Regino always gave us everything we needed. He was really good. Rivoredo is good too. When my brother caught a cough in São Luís and died, he gave me a machete.

One of the times we went to work with the whites in São Luís, we took some women with us. There was nobody there to make chicha (a drink made from manioc or maize) for us. Two of the women died from coughing. Now the women no longer want to go to the Tarüpa. Once Rivoredo took is in the motor boat from São Luís to the big river. There we saw a steam boat full of Tarüpa who stared at us a lot and wanted to buy our bows and arrows. We built a large barracão (store) and returned to São Luís. Many people had headaches because of the motor. The motor makes us sick and causes coughing. I’ve been to the Tarüpa five times to get an axe or a knife. One time, Regino came here and took us away to work. The black man Pedro also came with Severino when we were already living here. We stayed here for three days. They weren’t good.

They took us to work in São Luís, promising to give us axes, knives, shirts and trousers. But it was all lies. We worked but didn’t receive either axes or knives. Many other Tarüpa arrived to extract rubber. Last rainy season, we were visited by Tiboro, his wife Maria and Rosa and Ricardo (the journalist from Buenos Aires and his companions). They sang, danced and also drank a lot of chicha and didn't cough. That was good. Tiboro and Maria took many bows, arrows, hammocks and other things and didn’t give us axes of machetes. That wasn’t good. Now you’ve come. You’re not coughing either. That’s good. You work and hunt a lot of monkeys and you’re not bad. You’re going to stay here and never go away. We Tupari are few in number now. We’ve only two malocas, my own and Kuarumé’s. However we work hard and have a lot of maize, peanuts and yams for ourselves, our women and our children. And we drink a lot of chicha and sing and dance. That's good. Here, where we now live, few people now die. The Tarüpa say we should go to live in São Luís. But that wouldn’t be good for us. We want to stay here. It’s good to live in these large malocas. There’s a lot of disease among the Tarüpa and the rubber-tappers chase after all the women. Life there isn’t good. We want to go to São Luís only when we want axes and knives. So we work for Tarüpa and return again to our malocas. That way’s fine.” (1948:146-9)

As this account indicates, the presence of rubber-tappers, bosses and other whites during this period already had a decisive effect, bringing diseases to the village and asymmetric exchange relations. We can also note the role of the Makurap as the first and main interlocutors with the whites. Caspar comments that the Makurap language had become a kind of lingua franca in the region, spoken by most of the other indigenous groups. The ethnologist also emphasizes that contact between the Tupari and non-Indians was still fairly intermittent. They visited the rubber areas, offering to work in exchange for axes, machetes, clothing, salt and tobacco, and then went away for two or three years without reappearing. São Luís, the seringal (rubber extraction area) closest to the Tupari village, was from nine to ten days walk away.

The first seringal installed in the region was probably on the Branco river, close to the Guaporé river, in 1910. In 1912 a German opened another seringal on the Colorado river. In 1927 the Us company Guaporé Rubber Company opened a seringal in Paulo Saldanha. Around 1934, former employees of the SPI (Indian Protection Service) helped found a new seringal on the São Luís river (which in 1980 was transformed into the site of the Rio Branco Indigenous Post following the arrival of FUNAI in the area) (Leonel 1984).

Some rubber tappers from the region told Caspar about the disappearance of groups due to the diseases transmitted by whites – “they couldn’t stand the catarrh” – or the warfare (and cannibalism) in which the Tupari were embroiled. However, these groups also engaged in an intense cultural exchange involving marriages and chicha festivals. Before arriving at the Tupari village, for example, Caspar was invited to take part in a festival by an Aruá man (identified then as his village’s last survivor) also attended by Jabuti, Makurap and Tupari Indians.

During his stay, the main enemy group of the Tupari were the Hamno, described as ferocious head-hunters. But the ethnologist did not see any member of this group and that generation of Tupari apparently had not actually seen them either (ibid:148).

The Tupari and the official indigenist agencies

When Franz Caspar returned to Brazil and visited the group in 1955, he found them reduced to just 66 people due to a measles epidemic which had devastated the village the year before. The official indigenist agency (the Indian Protection Service or SPI) had lured them away from their malocas to work at the São Luís seringal, where they contracted the disease. The ethnologist estimates that more than 400 Indians from a variety of groups had died at the seringal.

The SPI had been absent from the region since the start of the 1930s when the agency transferred around a half of the population of these groups to a work colony nearer to Guajará Mirim, and later to the Ricardo Franco Indigenous Post (Caspar 1955:152). It was only in 1980 that Funai (the indigenist agency that replaced the SPI after 1967) established an Indigenous Post on the Branco river and that the territorial rights of the Tupari and other neighbouring peoples began to be recognized by the Brazilian state. During this period, the Indians who survived the great epidemics were already more resistant to the illnesses brought by the migrants. But the indigenist Mauro Leonel, who visited the area in 1984, identified dozens of cases of flu with complications and tuberculosis. Malaria, once almost non-existent, turned into an epidemic from 1983 onwards. In February 1984 there were more than 15 cases in São Luís village, without any medical care available locally (the nursing assistant was on extended leave and had not been replaced).

The relations with rubber bosses were marked by the debt peonage (‘aviamento’) system through which the Indians were pushed into a viscous circle of debt, forced to sell their labour in exchange for industrial goods sold to them at exorbitant prices in the ‘barracões.’ At the start of the 1980s, FUNAI published an identification report for what would become the Rio Branco Indigenous territory, which detailed the existence of 86 Indians semi-enslaved by a rubber boss. Further south, in an area that was later transformed into the Guaporé Biological Reserve, another 68 Indians were also working in semi-enslaved conditions for a farm owner. Only 33 Indians – children, the sick and the elderly – did not work for one of these two bosses in the debt peonage system.

In 1983, the Rio Branco Indigenous Territory was finally demarcated. However, its perimeter – then 240,000ha – left out seven villages. To the north, four villages near to the former seringal headquarters, mostly inhabited by Makurap, were left outside the boundaries to allow INCRA to donate these lands to 10,000 families in the Branco river colonization project. Also excluded from the demarcated area were another three villages, whose inhabitants – the majority Tupari – lived in an area close to the Guaporé Biological Reserve.

As well as the failure to demarcate the full extent of the indigenous lands, an invading rubber boss continued to exploit the labour of the Indians on their own lands. As Mauro Leonel’s 1984 report indicates, conditions at the Rio Branco Indigenous Post were awful, and the Indians themselves were left to transport sick people, goods and post employees, using the income obtained by the community canteen. This was created in 1980 with Funai’s support to compete with the barracão (store) of the invading rubber boss, until then the only supplier of industrial goods to the region’s groups.

For the functioning of the canteen, 30% of the rubber and 100% of the Brazil nuts sold by the Indians were committed to its upkeep, run by the head of the IP. However, due to the post’s lack of infrastructure, the owner of the barracão (store) could take the products to the sites where the families were working. Hence, despite charging more for the commodities, for many Indians these were easier to access than the canteen (Leonel 1984:204).

Even after decades of contact, it was only in 1987 that some Tupari visited a city. Until them they had only known the forest and the seringais. But from 1988 onwards, their lands began to be systematically invaded by loggers and they were pressurized by local economic groups to sell timber and allow the entry of prospectors (Mindlin 1993:17).

Productive activities

Agriculture is the main productive activity of the Tupari. Traditionally, Franz Caspar writes, the work in the swiddens was based on a sexual division of roles with men responsible for burning and clearing the terrain, as well as making the holes in which women then deposited the seeds and later harvested the crop, bringing the produce back to the village in bags woven from palm fibre. In Caspar’s era, the main crops were maize, manioc, yam, peanuts, sugarcane, banana, beans and a number of other kinds of root crop.

Today the Tupari villages are mostly made up of thatched houses with clay or stilt-palm walls. In 1948, the village visited by Caspar was composed of two malocas and the two largest swiddens were those of the chiefs of these communal houses. Everyone worked in these swiddens, but each man also had his own swidden where he planted his own tobacco and the food most liked by his family. Many men grew more sugarcane in their swiddens than the chief, especially when their wives liked it. They also planted cotton and annatto for their wives. The Tupari are also extremely fond of peanuts, which they cook or roast.

The large size of the chiefs’ swiddens allowed them to invite all the co-residents to the festivals, which were lavish and usually lasted three whole days. In Caspar’s words: “Possessing a field with immense plantations of maize, yams, taioba, peanuts and, above all, manioc, inviting his people and neighbours to festivals throughout the year and being considered a perfect host were the chief’s biggest challenge and the main display of his authority. To achieve this aim, the leader had to work much harder than his subordinates. He had to be the first to start and the last to return home. Only in this way would his people respect him and be willing to collaborate in the work. (...) Indeed, in the same way that each man had to help the ‘tuxaua’ (leader) to clear his swidden, the latter had to help each of them in turn. The number of collaborators and the sweat spent in felling the area were the clearest measure of his influence among the tribe” (ibid:129-30).

As well as swidden cultivation, the activities of hunting, fishing and gathering make up much of the daily routine in Tupari villages. In the 1940s, there were periods when almost all the Tupari would leave the maloca in small groups, armed with a bow and a bundle of arrows in their left hand and, on their backs, a small travel hammock and cobs of corn. They might hunt or fish for five to ten days. Many men took their women and children with them (Caspar 1948:191). Monkey meat was highly appreciated. They also hunted pacas, agoutis, curassows, lizards, armadillos and other animals.

While the men were away hunting, the women sometimes went on day-long journeys into the forest in small or large groups. They would return in the evening with their finds, such as small fish, crabs and other crustacea, larvae (eaten with honey), crickets, beetles and caterpillars of many species. These products were left to grill over a fire along with peanuts and roots before being consumed.

In the malocas, the ethnologist Caspar highlights everyday scenes such as women tending the fires, shredding or spinning cotton or making a small amount of chicha for quotidian consumption, picking lice or painting each other's faces and cutting each other’s hair. Every so often, a woman would chase away the chickens and ducks trying to peck at the food in the pans or on the grills, or anxiously grabbed a child crawling close to the fire and about to be burnt (ibid:131).

However, among the daily activities of the Tupari, Caspar emphasizes their consumption of chicha, made by women and consumed in lavish quantities during the festivals. “The manioc in the plantations and the maize stocked by the Tupari seemed to be inexhaustible. The festivals followed one after the other” (ibid:172). To make manioc chicha, the tuber is peeled, chopped and cooked to produce a paste, which is then chewed and spat into the pots. This paste is then pounded in the mortar, sieved and stirred. Afterwards the mash is left to ferment for a few days. To make maize chicha, women take large numbers of cobs from their stocks of maize, wash the large pots with water brought from the stream and fill these pots with maize kernels and water. They tip the cooked maize kernels into the wooden mortar where they are pulped. The fermentation process is similar to that for manioc.

Extractivism and the barracões

Decades after Caspar’s accounts, in the 1980s, the economic organization of the Tupari was described by the indigenist Mauro Leonel as a mixture of their traditional form and rubber extraction, Brazil nut harvesting and shelling for sale or barter in the market. During this period, the barracão (company store) system was in operation, involving the Indians selling their labour or forest produce for the industrial goods brought from the city and offered in the seringal stores and the canteen of the Indigenous Post.

Leonel adds that it was only after Funai’s arrival in 1980 that the Tupari began to have their own money, around US$50 to 100 per year for family head. The canteen and/or barracão systems provided them with the basic items: oil, matches, kerosene, machetes, sugar, salt, tools, batteries, soap, ammunition and so on.

The yearly cycle was as follows: in June the Indians began to build the rubber tapper houses and shelters and to clear the trails (in the rubber extraction areas). In September they paused to burn and clear the swiddens and plant manioc. In October they planted rice and maize. In November they returned to the seringal to extract, press and ‘fabricate’ the rubber, preparing it for sale. December and January were dedicated to collecting and shelling Brazil nuts. In February and March they harvested the swidden crops, especially maize and rice, and planted beans. April involved clearing the swidden undergrowth, followed by felling the larger trees in May (Leonel 1984).

The traditional family swiddens usually measured somewhere between 1/2 and 1 hectare. In general, people planted manioc, three varieties of maize, banana, rice, yams, peanuts, tobacco and sweet potato. When Leonel visited the region in 1984, there were seven swiddens to the north of the São Luís Indigenous Post and 21 to the south. Eight nuclear families had modest ‘flour houses’ where the manioc was processed.

All the Tupari activities are interspersed whenever possible by hunting and fishing. Timbó fishing is used by all the groups, but has been made more difficult by the construction of PCHs (Small Hydroelectric Dams: see Some contemporary challenges]. Game is very scarce, though hunters still find peccaries, armadillos, paca, deer, agouti, tapir, coati, monkeys and tortoises. They also hunt birds and collect honey, fruits and peanuts.

Craftwork was very rarely sold in the 1980s, but today it comprises one of the main sources of income for the Tupari. They often exchange or sell their famous tucum palm basket. Tucum fibre was also used to make bracelets and shell pendants. They still make bows, arrows and war clubs.

Way of life

The traditional rule of residence among the Tupari is uxorilocal, meaning that bridegroom goes to live with his father-in-law in order to work for him. If the husband is older, however, and especially if he is a leader, he takes the young woman to live with him.

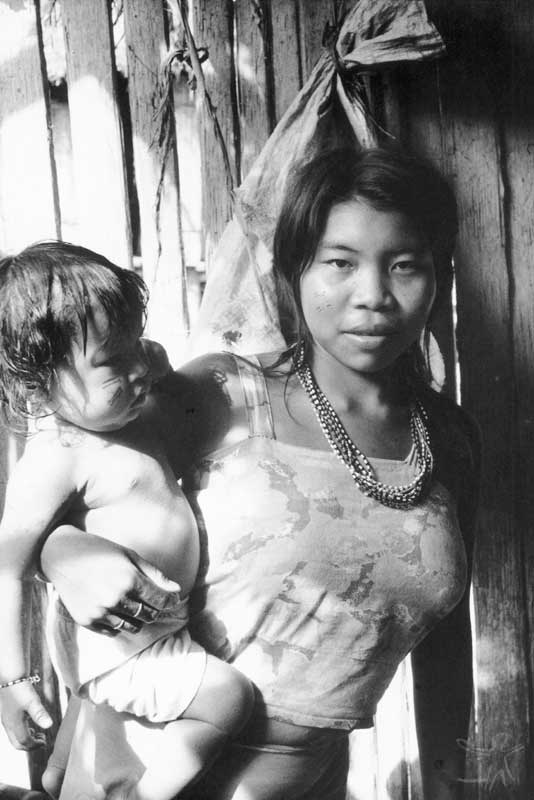

In terms of adornments, Tupari men used a yellow leaf to cover their penis. The nose was pierced along with the lips and earlobes. A tube about the thickness of a pencil or a small coloured stick was inserted through the orifice of the nasal septum, which almost filled the nostrils, opening them wider. Small lengths of fine wood were pushed through the lips, or two porcupine quills. Pieces of shell and glass beads were used as ear pendants.

People also used necklaces, bracelets and cotton bands on the wrists and legs. Some people used a belt of small black beads. Everyone, though, painted their bodies from head to foot with spots and black wavy lines. Some also painted their faces. Their smooth hair was parted down the middle, sometimes reaching the shoulders. They shaved their eyebrows and removed all body hair. The men also shaved their beards.

Communal houses were described by Caspar as circular and dome-shaped. The village was constituted by two communal dwellings. Caspar estimated that around one hundred people, or 30 families, lived in the main house. The smaller house had about ten families. The centre was not inhabited by anyone. A large circle of chicha pots was separated by a wide corridor. From this corridor, small passages led to the hammocks (ibid:86).

Between the two houses there was a small plaza with chicken coops and some store huts. In the plaza, the men would sit on small stools sculpted from wood.

Cosmology

In the past, the earth was not populated and in the sky there were no Kiad-pod [primitive shamans]. There was just a large block of stone, beautiful, smooth and shining. This block was a woman, though. One day it split open and, among the torrents of blood, she have birth to a man. He was Waledjád. Once again the block split open and another man was born. He was called Wab. Both were shamans. They had no women so each one made a stone axe and they felled two trees. After this they killed an agouti, pulled out its front teeth, and with this material sculpted a companion for reach of them. Other primitive shamans were therefore born, the Wamoa-pod, some from the earth, others from the waters.

Waledjád was very bad. He was always becoming angry and each time he lost his temper, he cried copiously. In this way, he flooded the entire earth, drowning many Wamoa-pod. The survivors did not know how to get rid of Waledjád. One of the primitive shamans, Arkoanyó, hid in the canopy of a tree and dripped liquid bees wax on Waledjád as he walked underneath. The wax glued his eyes, nostrils and fingers. This stopped him from causing anyone more harm. They wanted to take him faraway and many birds tried to carry him through the air, but they were all too small. Finally, a large bird appeared that was strong enough to pick him up and carry him off. He scooped up Waledjád and flew with him far to the north. There the bird abandoned him and he still lives there today in a stone maloca. When he gets angry, it rains here on our earth. Another bad shaman was called Aunyain-á. His teeth were big like the tusks of a white-lipped peccary. He frequently ate his neighbour’s children. Eventually, the latter decided to flee from this terrible being and abandon the earth. One day,

Aunyain-á went into the forest to hunt curassows. So they climbed up a very tall vine hanging from the sky down to the ground. During that era, the sky was not as high as it is today; it was suspended very close to the earth. When Aunyain-á came back from hunting, he was unable to find his neighbours. He asked a parrot where they had gone. The parrot told him to go to the river, but Aunyain-á could not find any footprints in the sand there. Then the parrot laughed and said that all the neighbours had climbed up into the sky. Aunyain-á became furious and wanted to kill the parrot, but his arrow shot missed. Aunyain-á began to climb the vine to grab the fugitives. The parrot quickly flew high above and began to peck the vine, which then snapped. Aunyain-á was hurled to the earth and shattered into pieces. From his arms and legs were born the caymans and iguanas; from his fingers and ankles were born every kind of lizard.

The rest of his body was devoured by the vultures. Since this time, the primitive shamans have lived in the sky. These are the Kiad-pod. Some remained on earth, but they live far from here. Many of these Kiad-pod looked like people, but they always possess their own peculiarities. One speaks through the nose, another has a twisted mouth and yet another, Wamóa-togá-togá, has a navel the size of the palm of a hand. None of them has hair on the front part of their head. The sky is also home to primitive shamans with an animal body. There is a capuchin monkey, a spider monkey, a howler monkey and many others who are all true sorcerers. They now how to speak and sing like people. When our shamans sniff tobacco and yopo [a hallucinogen] here in the maloca, the powder flies to the noses of the sky monkeys. They sneeze and come down from the sky to the earth in order to take part in the Waitó ceremonies [the Tupari shaman is providing the account]. Common people cannot see these sky inhabitants. Only the shamans communicate with them during the evocations. Then the Kiad-pod enter the maloca and the soul of our shamans goes to the sky and wanders through the distant regions of the earth. There the spirits give them mysterious yellow grains, the Pagab. The shamans can use the Pagab to cast spells and kill their enemies” (ibid:211-2).

Caspar also recorded the following account given by Waitó on how humankind appeared on the earth:

A very long time ago, there were no Tupari or any other kind of people on the earth. Our ancestors lived below the earth where the sun never appears. They felt very hungry, since they had nothing to eat apart from palm fruits. One night they discovered a hole in the earth and climbed out. The exit was not far from the maloca of the ancient shamans Eroté and Towapod. There they discovered the peanut and maize plantations of the shamans. They ate a lot and early morning disappeared again through the hole hidden between the rocks. They did this night after night. Eroté and Towapod thought that agoutis were stealing from their swiddens, but one morning they discovered signs of humans and found the hole through which they had come outside. They lifted up the rock covering the exit and used a long stick to poke inside the hole. The humans started to leave in large numbers until the shamans covered the hole again.

The humans were horrendous then. They had long tusks like the peccary and membranes between their fingers and toes. Eroté and Towapod snapped their teeth and shaped their hands and feet. Since then men no longer have pointed teeth or webbed limbs, but beautiful teeth, fingers and toes.

Many people remained inside the earth. They are called Kinno and live there even today. When all the people on earth die, the Kinno will come out of the ground to live here above.

The people removed from the earth by Eroté did not all remain living in the same place. We, the Tupari, stayed here, the others migrated further away in all directions. These are our neighbours, the Arikapu, Jabuti, Makuráp, Aruá and other tribes” (ibid:213-4).

The world of the dead

As well as Waitó, the main shaman, one of Franz Caspar’s other important informants was the young shaman Padi, who told Caspar about the spirits of the dead. He said that very faraway there is “a large stretch of water and a large village” where the dead Tupari live... the Pabid. Nobody can see them. Only the shamans can visit the Pabid in dreams. However, the Pabid were brought to the maloca in the shamanic sessions (ibid:182).

When a Tupari dies, the pupils of the eyes leave the body and transform into a Pabid. The Pabid do not walk on the earth as living humans: they journey to the realm of the dead walking on the backs of two gigantic caymans and two immense snakes, one male and the other female. Common humans cannot see these caymans, only the shamans see them while dreaming. Sometimes the snakes arches up towards the sky in the form of a bow, becoming visible during rains. This is the rainbow. The Pabid also meet ferocious jaguars who frighten them with their roars. However they do them no harm. Eventually, the dead reach their new home, located near to a large river, the Mani-Mani. In principle they see nothing since their eyes are still closed. As soon as they arrive, they are greeted by two thick, long worms, one male and the other female, who open a hole in their stomach and eat their innards. Afterwards they leave.

Then Patobkia arrives, the main shaman and the leader of the maloca of the dead. He drips the juice of a very hot pepper into the eyes of the recent arrivals, which finally allows the Pabid to see where they are. They look around in amazement and only see unknown people. Everyone has an empty belly since the worms have already eaten their intestines. Patobkia then offers them a gourd of chicha. The new Pabid drinks and Patobkia leads him or her into the village of the dead. Two very old shamans are waiting there for the recent arrival. When the Pabid is a man, he is obliged to have sex with the old female giant Waug'e while everyone looks on. If, however, the dead person is a woman, she will be possessed by the old man Mpokálero. After this the Pabid no longer copulate in the same way as the living; men blow a handful of leaves and magically send them into the belly of women. This makes the women pregnant and later give birth.

The Pabid live in large round houses; however, they do not sleep on hammocks but standing up, leaning on the house supports, and cover their eyes with their arms. They do not fell trees or cultivate the land. Patobkia performs all this work with magical gestures and his enchanted breath. The peanut chicha made by the Pabid women is not fermented, meaning that the dead can drink it without becoming inebriated. Even so, they sing and dance frequently, everyone wearing headdresses. The Tupari shamans hear their songs when they visit the villages of the Pabid in dreams.

As well as the Pabid, the dead have a second soul that does not go to the maloca of the Pabid, but rises into space some time after death. In Padi’s words:

"When a person dies and his or her pupils go to the Pabid, we bury the body in the maloca or where we have burnt an old maloca. Almost as soon as the body is buried, the heart begins to grow inside the body and, after a few days, it becomes as large as a child’s head. A small entity appears inside the heart and grows until it bursts the latter, like a bird bursts the eggshell. This is the Ki-apoga-pod. It cannot get out of the ground, though, and cries from hunger and thirst. The dead person’s kin therefore go hunting. On their return, they organize three snuff sessions with the shamans. The main shaman pulls the Ki-apoga-pod from the ground, washes it and forms its face and limbs. When it comes out of the ground, it looks like a shapeless lump of earth. The sorcerer gives it food and drink and releases it into the air. The Ki-apoga-pod live there above.

When the dead person was a shaman while alive, his or her Ki-apoga-pod does not fly into space but remains in the maloca. There the souls of the dead shamans eat the food and drink the chicha of the living. From the domed roof of the malocas, they enchant the living during the night and make them dream. The souls of the shamans’ wives also hover there” (ibid:195-7).

Rituals

During the period when Franz Caspar was living among them, the Tupari believed that a woman would not become pregnant if one of the demiurge shamans, Antaba or Kolübé, exploiting the darkness of the night, did not visit her brining a child. This child grows from the flesh of the two Kiad-pod and is more or less the size of the palm of a hand. After detaching it from their own body, the sky spirits approach a sleeping woman and, using spells, insert the small entity in her breast. There it grows and later emerges into the world.

When the child was born, the mother would scrape her child’s brow with a grass stalk and paint his or her head with genipap. She would pierce the earlobes and insert a thread of palm leaf fibre through the holes. The child’s face was decorated with black lines and dots in the same way as adults (ibid:188).

When the child was old enough to eat palm larvae, the parents had to fast for five days. Afterwards they took part in a ritual supervised by a group of shamans, involving herbal baths in pools, surrounded by yopo powder, the consumption of monkeys killed by the child’s father, chicha and other delicacies. The culminating point of the ritual was when the child ate a palm larva for the first time (ibid:128).

Female initiation

When a girl menstruated for the first time, her mother communicated the fact to the main shaman. A screen of palm leaves and mats was erected in the maloca behind which the girl remained in seclusion. For five days she received no water or food, until the shaman blessed a pot of unfermented chicha for her. Chicha also comprised the girl’s main source of alimentation during the subsequent months. She could not touch meat or fish under any circumstance. She could not leave the compartment, have a bath or even wash. She remained sat on the ground or in a small hammock, spinning cotton to be4 used later to weave a hammock for her husband. If she already had a husband, she could not see or talk to him throughout this period.

The girl’s reclusion was only suspended after two or three months. The girl’s husband and her closest kin left to hunt for ten days. The young woman, however, needed to fast strictly for another five days and the women spread damp and putrid soil over her head to soften the hair roots. When the hunters returned, the shamans performed a ceremony in conjunction with them. All the participants snorted tobacco and yopo powder, while the main shaman cast spells over the girl. The women pulled out her hair and her body and bare head were painted with red and black paint. The girl then finally received some food again and returned to the tribal community. But she could only live with her husband when her hair had grown fully (ibid:200-2).

Chicha festivals

According to the survey by anthropologist Samuel Cruz (of the NGO Kanindé), today the traditional festivals only take place once a year. But Caspar states comments numerous times in his work on the frequency with which the Tupari held festivals, which often lasted three whole days and in which vast quantities of fermented manioc and maize chicha were consumed.

People ate large amounts of game meat and drank lavish quantities of maize chicha, interspersed by vomiting. In the words of the ethnologist: “It’s part of the festival: drinking, vomiting, drinking, vomiting, until dawn comes” (ibid:52). They made bamboo musical instruments and danced until sunrise, as the author describes:

“A dozen musicians formed a circle around a stick thrust into the ground. They held the bamboo instrument in their left hand and rested their right hand on the neighbour’s shoulder. The dancers moved in a circle, taking small steps to the side, to the sound of a simple melody. Soon other dancers joined them. All of them carried a bow and arrows in their hand, or a sword [made from palm tree wood with two edges] over the shoulder. The women formed an outer circle. They either held hands or held on to each other’s waist or shoulder.

The circles moved round slowly in pace with the music. From time to time, they marked the beat, making a few steps backwards in the same rhythm and then, with a wild cry, began to rotate again slowly to the right. The musicians played the solo, then the dancers sang in chorus. A distinctive rhythm announced the end of the dance after a quarter of an hour, more or less. The dance circle stopped. The Indians let out a ‘huuuuuuh!’ Then they ran to fill their gourds and squatted next to the fires lit during the songs. The musicians began a new session” (ibid:101).

Both men and women drank heavily. Though women are responsible for producing chicha, in the male festivals the men served the women, though in much smaller portions. In the women’s festivals, however, the women were the ones who drank and only occasionally offered drink to the men.

In all festivals, the Tupari painted themselves with genipap sap. The women chewed the green fruits and spat the juice into a small gourd. The juice was spread on the body with a wad of cotton. At this point it is almost invisible, but it later penetrates the skin and turns blue-black. The designs of wavy stripes, crosses and dots took a week to fade away (ibid:81).

When he heft the village after months living among them, the Tupari asked Caspar to remove his shirt. Then some women began to rub their bodies up against the ethnologist. This gesture was explained by one woman as follows: “We cooked for you and gave you food. Now we need to eat again our breath that is inside you.” Afterwards the children did the same, which was explained thus: “You played with them and carried them!” Consequently, the ethnologist could not leave without removing his breath from inside the children and making it return to himself, since later he might miss it (ibid:217).

Shamanism

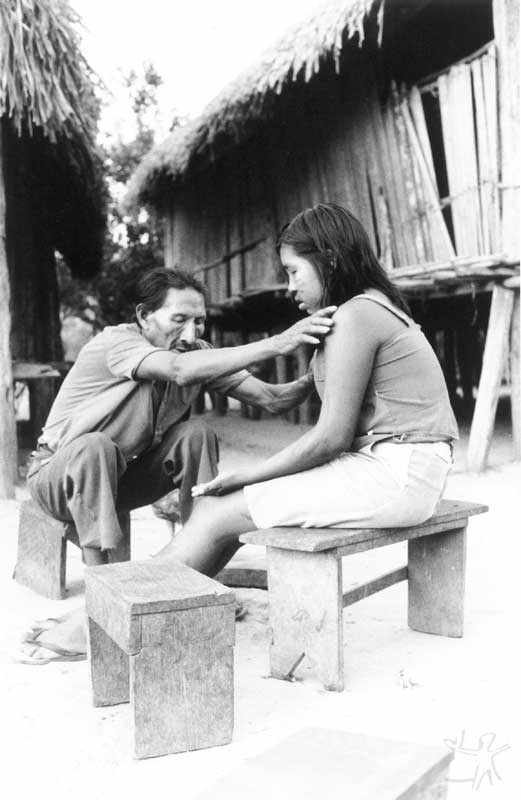

According to the anthropologist Samuel Cruz (from the NGO Kanindé), all the Tupari villages have a shaman who makes use of yopo seeds with their high hallucinogenic content. These are macerated until they turn into a powder and then mixed with a special variety of tobacco grown for this purpose. This mixture is inhaled through a length of bamboo: one end has a container holding the powder, which is placed under the shaman’s nostril, while another person blows from the other end.

Caspar witnessed various sessions of shamanism during the time he spent among the Tupari. During one of them, an old woman moaned in pain. The shaman Tadjuru, squatting on his heels, wiped his hand over the patient’s body and then raised his arms in the air, apparently removing something from his own limbs and allowing it to penetrate the women. To terminate, he leant over the immobile patient and sucked the nape of her neck. Still squatting, he crawled across to the door where he spat out the affliction he had sucked from the old woman’s body (ibid:75).

The shamanic cure sessions usually involved sucking out and spitting the sick person’s affliction. But one time when a man was seriously ill, Caspar had the chance to witness a different kind of session directed by Waitó. The sick man’s wife brought an immense pot containing a roasted capuchin monkey.

The monkey’s head was then chopped up and the shaman rubbed it over the patient’s body, exorcising foreign elements, breathing out heavily and clicking his tongue. Later Waitó explained to the ethnologist that the monkey head had the power to suck diseases from the body and devour them (ibid:194).

Describing another shamanic session, the ethnologist recounts that a dozen men (shamans and apprentices) formed a semicircle. The participants removed the small sticks from their nasal septums and Waitó and Kuayó (the first and second shaman, respectively) blew almost twenty pinches of snuff (as the yopo powder was called) into the nose of each man. The two men themselves snorted around forty pinches. The four shamans present turned round on their stools to face the maloca’s doorway and performed a series of exorcisms. In the words of the ethnologist: “They waved outside with their right hand, puffed and blew, picked invisible things from the air and flung them away. They emitted strange sounds; they seemed to be asphyxiating. Meanwhile, they tried to grab with their hands a mysterious entity that remained completely invisible to myself. Finally they collapsed exhausted onto the stools, mumbling incomprehensible words” (ibid:107).

In these sessions, the spirits who arrived with the shamans were also frequently fed, in particular with roasted monkeys and maize chicha. Caspar comments that both in the couvade practices (observed when a child is born, as described in the section on Rituals) and the funerary rituals, the shamanic sessions were preceded by hunting monkeys, which were offered to the spirits and later consumed by the participants of the rituals.

Among the instruments, the ethnologist emphasized a rattle made from a round Brazil nut shell, the size of a fist. This was used to call the spirits of the dead. Caspar witnessed a shamanic session for a child who had died days earlier to travel to the sky. As well as the elements described above – the herbal baths, yopo, chicha, roasted monkeys and other delicacies, such as maize and peanuts – this ritual also involved an arrangement of body adornments on a palm leaf mat: “feathers for the ears, small sticks for the nose and lips, cords for the arms, bracelets, a necklace of small shell disks, a comb, a small ball of annatto dye and a gourd full of oil” (ibid:184).

After two rounds of snuff, invocations and the incessant use of the rattle, the spirits arrived. Waitó approached them filled with respect. He was the only shaman permitted to stand up with impunity and walk tall through the sacred sphere. Waitó turned to one of these spirits, which Caspar presumes to be the dead child, washed it with fresh water and then combed its hair. He then offered it the adornments for its ears, noise and lips, then the necklace, bracelet and armband, always one at a time so that the spirit had time to put on the adornment. To finish, he rubbed the Pabid with oil. Finally, he gave food to the other Pabid. Waitó held out a mouthful of food with his fingers and offered it patiently to the invisible beings. He then used a tiny spoon to fill a gourd of chicha and offered the drink to the guests. The only thing he did not offer were the monkeys.

Eventually the spirits went away. Waitó accompanied them with his arms raised as far as the exit, chanting a song. As soon as the Pabid had vanished, the Indians rushed to eat and drink, shaking their hands in the air. They explained to Caspar that they were eating the breath of the Pabid. “the ceremony ended after almost five hours. The shamans were exhausted and the followers could finally take a refreshing bath and quench their thirst with the chicha that awaited them in the bulging, full vessels” (ibid:185).

Sources of information

- ALVES, Poliana M. Análise fonológica preliminar da língua tupari. Brasília : UnB, 1991. 96 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CASPAR, Franz. A aculturação dos Tuparí. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 486-515.

- --------. Die Tuparí ein indianerstamm in Westbrasilien. Berlin : Walter de Gruyter, 1975. 442 p.

- --------. Tupari : unter indios im urwald brasiliens. s.l. : Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn Braunschweig, 1952. 218 p.

- --------. Tupari: entre os índios, nas florestas brasileiras. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1953. 225p.

- MINDLIN, Betty. Tuparis e Tarupás : narrativas dos índios Tuparis de Rondônia. São Paulo : Brasiliense ; Edusp ; Iamá, 1993. 123 p.

- ------- e narradores indígenas. Moqueca de maridos. Mitos eróticos. Rio de Janeiro ; Rosa dos Tempos, 1997. 303 p.

- PRATES, Laura dos Santos. O artesanato das tribos Pakaá Novos, Makurap e Tupari. São Paulo : USP, 1983. 149 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- O Tapir. Dir.: Raquel Coelho. Vídeo cor, 4 min., 1996. Prod.: School of Visual Arts; Raquel Coelho