Surui Paiter

- Self-denomination

- Paiter

- Where they are How many

- MT, RO 1375 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Mondé

Since 1969, when the Paiter were “officially” contacted, their relations with non-Indians have produced profound changes in their society. These changes, however, have not extinguished their warrior spirit, which has motivated the struggle of these people for the recognition and integrity of their territory. In their recent history, this has been terribly threatened by the violence of the Polonoroeste program, the corruption and omission of government agencies, the invasion by unauthorized individuals, including lumbermen and miners. Struggling as they can against these adverse conditions, the Paiter seek to maintain the vitality of their cultural traditions, in which society is understood through a division into halves, in such a way that the social segments, productive activities and ritual life constitute expressions of dualism between the village and the forest, the garden and hunting, work and festival – with the exchange fests of offerings and the work parties associated with them being the high points of exchange and alternation between these halves.

Name e language

The Suruí of Rondônia call themselves Paiter, which means “the true people, we ourselves". They speak a language of the Tupi group and Monde language family.

Despite the pressures that they have suffered from the non-Indians, which have caused various changes in the group, the Paiter still maintain many of their traditions, both those that have to do with material culture and with cosmological aspects, which are both related to the culture of other Tupi Mondé groups.

Location

The Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land, where the Paiter live, consists of an area of 247,870 hectares located in a frontier region, to the north of the municipality of Cacoal (state of Rondônia) up to the municipality of Aripuanã (state of Mato Grosso). One gets to the area from Cacoal, following access lines 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 14, due to the fact that the villages are distributed along the area’s borders, both for reasons of security and to take advantage of the old ranches left by invaders who set up their establishments inside the area in the decades of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

The term "lines" which is used in the region, and derives from the demarcation of plots from the colonization projects and frontier expansion, refers basically to roads that provide access to otherwise inaccessible places, at the same time they geographically mark the area.

The Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land is located in the Branco River basin, tributary of the Roosevelt River and which is formed by the junction of the Sete de Setembro and Fortuninha rivers. The main tributaries of the Branco River that drain the area are the Ribeirão Grande, Fortuninha River and the Fortuna, on the right bank. On the left bank there are the Igapó (named by the Paiter), the São Gabriel and other rivers with no name on the topographic maps of the IBGE.

According to descriptions made by the RADAMBRASIL Project- a 1978 project of the Ministry of Mines and Energy/National Department of Minaeral Production, the objective of which was to map the Amazon region in order to do a natural resources survey-, in the area where the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land is located there are three types of forest covering: open tropical forest, which is the largest area, dense tropical forest, and the area of ecological tension, which the smallest of the areas.

The predominant climate is hot and humid tropical. The average annual temperatures fluctuate around 24º C with two well-defined seasons, with a sharp decrease in precipitation in the winter, and three months of drought(june - july – august).

Population

The Suruí of Rondônia call themselves Paiter, which means “the true people, we ourselves". They speak a language of the Tupi group and Monde language family.

The plural of is paiterei, but, for the purposes of standardizing indigenous names in Brazil, here they will be called the Paiter.

The Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land has a population of 920 people (in 2002), distributed in eleven villages which are arranged along the access lines, which constitute a protection base against the entrance of the whites in their territory. There are villages along lines 8, 9, 10, 11 (four villages), 12, and 14 (two villages). The population in each village is variable, with 45 people in some and hundreds in others. The village of line 14 is the largest of all, with around 30 families. The newest village is Gaherê, in Pacarana, built in 2003, with six families.

Below is the population distribution by age bracket according to the report of the PACA (Cacoal Environmental Protection / 1999 -2000).

Paiter population - Age bracket

| Age bracket | Male | % | Female | % | Total | % |

| Under 01 year | 15 | 3,6 | 10 | 2,8 | 25 | 3,3 |

| 01 a 05 years | 94 | 22,8 | 47 | 13,3 | 141 | 18,4 |

| 06 a 10 years | 70 | 17,0 | 78 | 22,0 | 148 | 19,3 |

| 11 a 15 years | 61 | 14,8 | 57 | 16,1 | 118 | 15,4 |

| 16 a 20 years | 49 | 11,9 | 44 | 12,4 | 93 | 12,1 |

| 21 a 25 years | 28 | 6,8 | 24 | 6,8 | 52 | 6,8 |

| 26 a 30 years | 19 | 4,6 | 18 | 5,1 | 37 | 4,8 |

| 31 a 35 years | 21 | 5,1 | 26 | 7,3 | 47 | 6,1 |

| 36 a 40 years | 19 | 4,6 | 15 | 4,2 | 34 | 4,4 |

| 41 a 45 years | 10 | 2,4 | 15 | 4,2 | 25 | 3,3 |

| 46 a 50 years | 11 | 2,7 | 7 | 2,0 | 18 | 2,3 |

| 51 a 55 years | 2 | 0,5 | 8 | 2,3 | 10 | 1,3 |

| 55 a 60 years | 5 | 1,2 | 4 | 1,1 | 9 | 1,2 |

| Above 60 years | 8 | 1,9 | 1 | 0,3 | 9 | 1,2 |

| TOTAIS | 412 | 100 | 354 | 100 | 766 | 100 |

Source: Paca. Report of Activities Appendix II, Consolidated - Suruí, Period: October/ 99 to July, 2000.

In the graph referring to the year 2000 it is possible to see better the drastic decline of the population in the age bracket between 26 and 30 years, at the time of the large number of deaths due to infecto-contagious diseases. This dying was greatly accelerated in the ‘80s and decreased relatively at the end of this decade. Since 1989, one perceives a population increase among these people.

History of contact

The Paiter have an oral tradition, transmitted from father to son, about a time when they migrated from the region of Cuiabá to Rondônia, in the 19th Century, fleeing from the persecutions of the Whites. In this flight, they entered into conflict with other indigenous and non-indigenous groups. From the end of the 19th Century to the 1920s, with the exploitation of rubber, the building of the Madeira-Mamoré railway and the installation of telegraph lines by Rondon, the migratory flow to Rondônia was great and its effects were felt by the indigenous population in the region, causing many conflicts and deaths.

From 1940 to 1950, a new economic cycle of rubber exploitation and cassiterite mining were responsible for a 50% increase in the population of the then Guaporé territory (created in 1943 and which later was called the “Territory of Rondônia" in 1956 in homage to Cândido Rondon). Consequently, above all from the ‘50s on, once again the Suruí Paiter had to abandon their villages. This time is remembered in songs and stories, such as that of the hero Waiói, who had already lived with non-Indians in the beginning of the 20th Century and who, though no-one believed him, told his people about the lives of those people who ate rice and beans and had pots, machetes, axes and firearms.

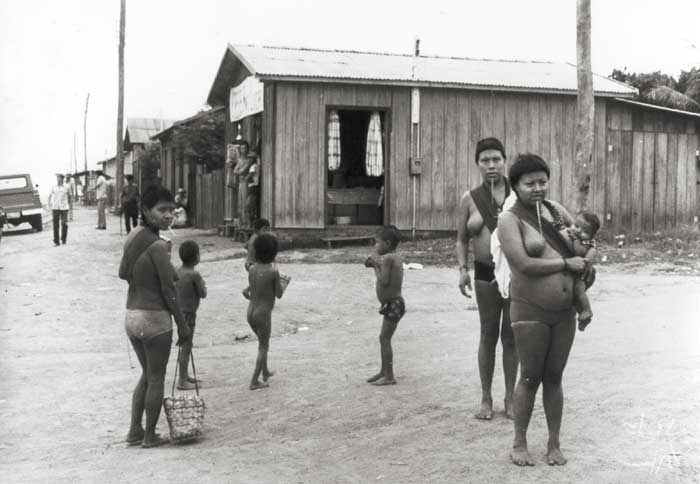

The migration became even more intense from the ‘60s on, when Rondônia became one of the areas of major agricultural expansion. The Cuiabá-Porto Velho (BR-364) highway was concluded in 1968 and the population of Rondônia grew from 85,504 in 1960 to 111,064 in 1970 and to 490,153 in 1980. Between 1977 and 1983, the number of migrants is calculated at 271,000, representing 14% of the total population of the state in 1980. Growth on such a scale resulted in land conflicts and pressure on the indigenous areas. The situation of economic growth and increase of the social inequalities exacerbated conflicts between Indians and ranchers, agriculturalists, rubber-gatherers and other groups engaged in extractivist activities.

The Suruí Paiter were officially contacted by the Funai in 1969, by the backwoodsmen Francisco Meirelles and Apoena Meirelles, on the then camp of the Funai, called Sete de Setembro – established the year before on the same day, the seventh of September, - when they visited the camp that year (the name of the camp is also the name of the main Suruí village next to the post). The Suruí only came to live at the post definitively in 1973, when they sought medical assistance from a measles epidemic that killed about 300 people. About a third of the population continued to live outside the indigenous area, near the town of Espigão do Oeste, moving in 1977 to another Funai post that had been established at line 14.

The turbulent history of demarcations and “dismarcations”, that characterized the creation of a good part of the indigenous lands of Rondônia, also applies to the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land created for the Paiter. The demarcation of this Indigenous Land was done in 1976, and permanent possession was declared in decree 1561 of September 29, 1983, by the then President of the Funai Octavio Ferreira Lima, at which time it received the official name of "Sete de Setembro Indigenous Area". Its homologation was approved in the same year through decree nº 88867 of October 17, 1983, by President João Figueiredo.

From 1982 to 1987, they suffered intensely from the impacts of contact with the non-indigenous society, as a result of the migration of thousands of people to the region due to the Polonoroeste Program (Integrated Program for the Northwest of Brazil), the key part of which was the asphalting of the Cuiabá-Porto Velho highway, partially financed by the World Bank. In this context, the Indians lost half of their territory to colonization projects and companies, which ignored the legal homologation of their lands. The Suruí even saw their lands invaded by small agriculturalists, pressured by extractivist companies and pushed to the interior of the indigenous lands. Such invasions had serious consequences for Paiter health, particularly among the children.

From the ‘80s on, several young Paiter fluent in the Portuguese language, because of the need for dialogue with the Whites, took their claims to the Funai. At that time, Suruí consciousness grew, of how Brazilian society is made up and also the need to struggle for the defense of their territory and cultural viability. The Paiter made trips to Brasília to accompany the administrative moves of the Funai and to make claims. In this context, several traditions were renewed and the work parties and festivals persisted, although the Paiter adapted themselves to new agricultural patterns, such as the cultivation of rice and a greater dispersion of the population.

Invasions and co-optation

The warrior disposition of the Paiter has been one of the main forces behind an effective resistance by these people against invaders and exploiters of their territory. From 1971 to 1981, there was a series of armed clashes between the Suruí and invaders. It is estimated that there were around a thousand non-indigenous families in the Indigenous area. Despite the interdiction of the area, the Incra went on stimulating the illegal entrance of migrants into indigenous territory, illegally selling them plots of land. The Itaporanga Company (Melhorança Brothers ) was responsible for the placing of several families in the indigenous area.

In view of the conflicts, the governor of the then Territory of Rondônia (Humberto da Silva Guedes), the Minister of the Interior (Rangel Reis), the President of the Funai (Ismarth de Araújo) and the Projects Coordinator of the National Institute for Agrarian Reform (Hélio de Palma Arruda) visited the indigenous area with the intent of pacifying the situation and solving the problems. The government demarcated the area moving the borders of the area back 9 kilometers on the southern part and between 12-15 kilometers in the eastern part. In order to hold back the invaders, part of the demarcation had to be done with the help of the Military Police. The Funai did not succeed in holding back the squatters, who refused to leave even with the land being demarcated, and they destroyed the landmarks and plaques of the Funai.

In 1978 the invaders closed the road from Riozinho to the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Post, preventing the entrance of Funai employees and vehicles, which caused further conflicts with the Indians. The Funai requested the support of the Army, which sent its Frontier Grouping to remove the invaders and make an official register which determined that there was a total of 652 people or 169 families.

In November, 1978, the indigenous land was invaded by 20 families, who took possession of 10% of the territory. In the beginning of the following year, the Paiter threatened the invaders, who had built a 20 kilometer road and installed a sawmill and a rice husker within their territory. The conflicts worsened and the Minister of Agriculture (Delfim Neto) promised to remove the intruders from the area and settle them in another colonization project. However, he never kept his promise. In September, the Paiter received a visit from the President of the Funai (Adhemar Ribeiro), who also promised to remove the invaders. A month later, it was the turn of the director of the Incra, who promised to remove the invaders in April, 1980. The months passed and the invaders continued on the indigenous land, questioning the quality of the plots that the Incra was offering. The Funai convinced the Paiter to not attack the invaders, claiming that the Justice Department would take them out of there. Certain that they would continue there, the invaders filed suit for Maintenance of Possession in the Court of Porto Velho and the Funai responded with a plea for Reintegration of Possession. The invaders won, through a holding action granted by the Judge of Porto Velho, the right to remain 90 days on the indigenous land. The Funai appealed and the holding action was annulled.

Tired of waiting for actions from non-Indian Justice, in October the Paiter expelled several of the new invaders making them leave their lands naked and unarmed. In October, 1980, there were 87 families of invaders living inside the indigenous land, who were gradually removed – receiving lands in colonization projects, this being the first time that this had occurred in indigenous history – and, one year later, there were only three families left. In 1981 all the invaders had been removed, and the Paiter went on to living in already formed villages where there had been coffee plantations left by the non-Indians.

Polonoroeste

In the years from 1982 to 1986 the Brazilian government launched the Program for Integrated Development of the Northwest of Brazil (POLONOROESTE), involving an investment of 1.55 billion dollars, of which only 2.5% would go to the environmental component and 1.4% to the indigenous component. In the contractual agreements, the federal government and the government of Rondônia assumed the commitment to protect the areas legally defined as reserves.

In this period, the Federal Territory of Rondônia underwent economic transformation and received approximately 200 thousand migrants per year, along with lumbermen, mining companies, land speculators and jumpers, which meant numerous invasions and deforestation on indigenous lands. The land of the Paiter was once again invaded, causing social disorganization and a frightening increase in diseases.

The poor administration of resources made available by the POLONOROESTE meant a lack of money to meet the health needs and to commercialize the products of the Paiter; consequently, in 1987, the FUNAI employees stimulated several indigenous leaders to sell lumber. It is estimated that about two million dollars worth of lumber have been taken out of the indigenous area (CEDI, 1992).

Lumber and mineral prospecting

Besides the nearness of the city and imitation of the colonists’ modes of living, the Funai was responsible for the introduction of a dietary pattern based on rice, beans and sugar, which meant a new form of planting and a new set of habits with definite times for eating, recreational, and planting activities. Little time was left over for hunting, fishing, and holding the traditional festivals. The Paiter, in terrible health conditions, sought assistance in the hospitals of Cacoal and in the Indian House in Riozinho. Under such adverse conditions, it was easy to give in to the enticement of the lumbermen and corrupt employees.

One can thus understand this willingness on the part of the Paiter to enter into accords with lumbermen as a desperate response of the group in view of the lack of resources – above all due to the absence of public policies that would guarantee their quality of life and the integrity of their territory – to confront the impasses created by this cultural frontier situation, which produced a state of anomie in Paiter society.

In the second half of the ‘90s, there was still mineral prospecting activity on the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land. However, as there was little gold to be found, it didn’t take long for it to lose its force – different from what happened among the neighboring Cinta-Larga, who greatly suffered from the situation of violence and social anomie resulting from the diamond prospecting on their lands.

The accumulation of goods made possible by their – partial and temporary – insertion to the lumber and prospecting market motivated many Paiter to go live in the city of Cacoal, where they have suffered enormously from prejudice against their indigenous identity, being looked upon as privileged due to the aboriginal rights guarant

Social organization

The Paiter are organized into moieties comprised of patrilineal exogamic groups: Gamep, Gamir, Makor and Kaban. The Paiter are polygamous. They practice avuncular marriage, referring to the rule of marriage in which the man marries his sister’s daughter. There also occur marriages between cross-cousins; parallel cousins, however, are considered brothers/sisters and cannot intermarry.

The presence of the Baptist and Assembly of God religions in the villages has contributed to a profound transformation in their culture. An example of this is the disappearance of the pajés [shamans]. According to informants, numerous pajés have ceased practicing due to the prohibition of the Church. This is clearly stated by Almir Narayamoga Suruí:

"We have many pajés who do not practice because of the religions. The spirits of the animals speak with the pajés and, due to the religions, the Pajés have said to the spirits that they didn’t want to be Pajés any longer, for the spirits were jealous of the god of the religions".

Political Organization

With regard to political organization, Suruí chieftaincy is diffuse. There are many chiefs, of the various clans and villages, and the most powerful of them have the largest gardens and customarily are more generous in providing "chicha" (fermented corn beverage), besides being outstanding in the art of producing arrows. There are also ceremonial chiefs for the collective labor parties. Each clan has a chief and the chiefs change from time to time, the position being transmitted from father to son, or from one brother to another if the chief has no sons. The most common form is for a man to be a chief of a group of brothers, although a woman’s father can be the chief among his daughters’ husbands if they live in the same house. For representing the people before agents of the national society, the Suruí elect younger chiefs who speak better Portuguese; however, in the village setting, chieftaincy continues to obey the traditional patterns.

Because they are not politically centralized, on certain occasions the lack of consensus among the local leaders has brought on internal conflicts and has made unviable the taking of a certain position representing all of the Suruí people.

The longhouse and daily life

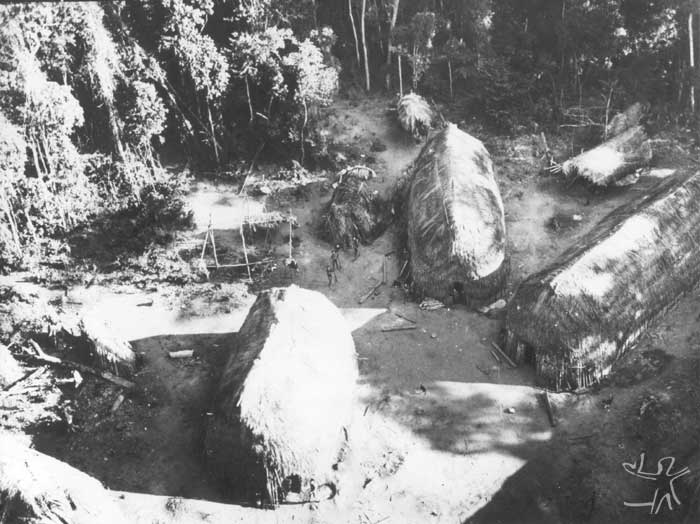

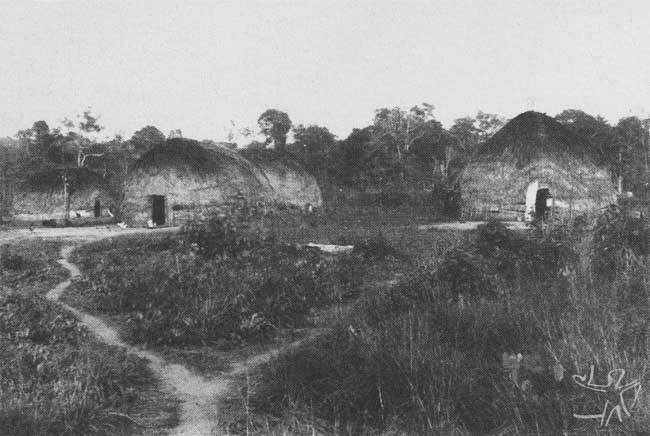

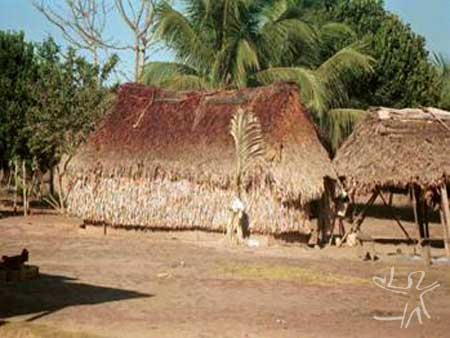

Traditionally the Suruí Paiter lived in communal houses divided internally according to family groups. Today, the situation has changed a great deal; however, in order to better understand social organization, we will illustrate how traditionally houses were organized.

The houses are long, shaped in the form of an ellipse, measuring about 25 by 8 meters, with a single door on the more narrow part. They are tall constructions, in the shape of a Gothic arch, and may be as high as 8 meters. The frame is of wood and is covered with thatch. Treebark, half a meter high, forms the base of the wall that protects the house from rain, the rest being of thatch.

At the entrance there is a space for common use, where, among other objects of household use, there are large ceramic pots, belonging to each woman of the house and which are used to make various kinds of soup and ceremonial drink called "i", made from corn. On the days when the women cook together, squatting, with long bamboo spoons, one can hear in the early morning the sound of the mortar, where the corn is being pounded for soup or flour. Also, every day the women make the regular movement, on foot, of bending the trunk up and down and holding the heavy pestle.

In the other spaces of the longhouse, pairs of wooden posts (joined by beams about a meter and a half from the ground) divide up the nuclear families (a married couple and children). On these beams, five or six people hang their hammocks, one next to another. There are few objects, only the food brought from the garden for two or three days, some game meat or fish, and a few pieces of corn bread. On the ground, there are clay pots, small mats set by the posts, when not in use, and one or another basket. In high places, bananas are strung up to ripen and corn for seeds and other uses; there also they keep arrows, ornaments, and, today, suitcases or baskets with clothes. The wooden frame is useful for keeping small belongings, and for sticking in mirrors and combs.

The marriage system reveals in part the occupation of the spaces of the large longhouse. As they are polygamous, several men with two or more wives, many of the wives sleep in compartments separate from their husband.

Each small family group has a fire for cooking, besides the larger fire and buckets at the door. Below each hammock, a fire is made and at night the women wake up all the time to get more firewood and kindle the flames. In this family scenario, the place of the head of the house is the first to one of the sides of the door, where he lives with one of his wives, and from there the house is divided up into several compartments, each family compartment being a unit of social life. There people converse, lying down or sitting, passing around husked corn. The hammocks swing back and forth and the bodies warmed by the fire touch each other; while babies are passed from one hand to another. Each nucleus is connected to another and from one hammock, a person converses with everyone else in the longhouse, children go back and forth bringing chunks of food kept in baskets, women sweep the floor, others are seated on mats in small groups doing small chores and at times talking in low voices.

The house is far from being a quiet place. Everything happens there, the stage of many stories, each of which has its refuge in hammocks that shelter from the violent heat and from the sweat of the gardens. The longhouse is a fresh and cool place, the darkness reduces the burning sun to a point on the door. From one house to another food circulates following the obligations of kinship. Little earthen pots or baskets coming and going, and there are also constant quick visits to the house of a brother or affine who has brought meat.

Present-day Dwellings

Today, the elders of the villages continue to live in longhouses. But the number of wooden houses (with asbestos or mud covering, wooden walls and polished cement floors) has been increasing) and there is even one or another of bricks, following the architecture of the houses of the colonists. In these houses, instead of domestic groups, there are nuclear families.

Half from the forest and half from the garden

The members of the clans that comprise Suruí society share the same set of social rules, and have obligations to each other. They are separated, in community life, in two halves, one connected to the forest and the other to the garden, which means that the families change sides in annual cycles, thus, those from the forest goes to the garden and vice-versa. In the garden, for example, there is broad cooperation among the members of this half, beyond the same cooperative attachment that exists among brothers and sisters’ husbands. These, in turn, have the obligation to give mutual assistance to each other. Traditionally, all economic activities are organized around kinship.

Thus each half shares the idea that everyone in that half has commitments to their side, in the various types of possible labor in hunting, gardening, and making of objects, each implying different demands on labor activities.

The opposition between forest and garden organizes the annual calendar of the Paiter. The division between the halves determines various moments of social life, including food production, festivals and rituals.

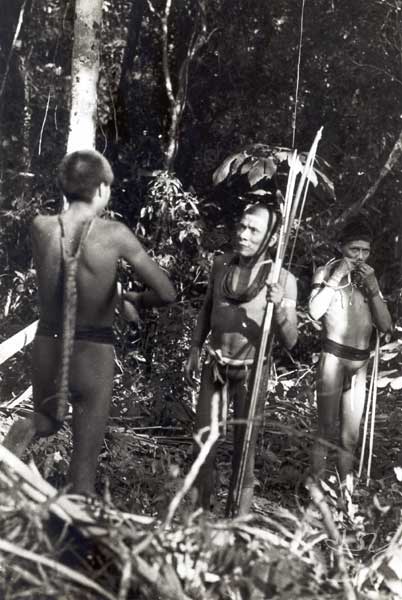

The forest half is installed during the dry season (May to October) in the metare, which means clearing or thin forest, from 500 to a thousand meters from the village, a place which is prohibited to the other half.

In the Mapimaí, the great festival in which trade takes place between the two halves, the íwai, group from the garden or of food, are the hosts. The íwai should provide makaloba in the festivals, a fermented beverage which is greatly appreciated by the Paiter. Made of yams, manioc, corn or other products that yield flour, makaloba is drunk in quantity by men and women.

It is necessary to know the forest well to know what metare means, a clearing connected to journeys, to the pleasure of the expeditions, unexpected findings, to suddenly abundant food, without it being necessary to wait for the rhythm of the seasons and for the growth of the plants that the garden demands.

While the íwai, the half connected to food, need larger gardens for their offerings and have to dedicate more time to gathering and cooking, those of the metare stay in the forest during the dry season, although they continue to work in the garden as the others do. A set of temporary shelters is built in a semi-circle for each nuclear family in the clearing selected for the metare. The arrival in the camp takes place in the midst of much noise and the men, in a festive mood, make arrows, bows, feather or straw ornaments, headdresses, all the while conversing and joking. The women make ceramic objects, collars, baskets, they spin and weave straps to carry the children, besides cotton belts and collars, all dyed with much red urucum. In the village these objects are also produced, but in the metare the artisans are altogether and working towards the festivals. In the metare there is more time for hunting and fishing and the roasting racks are always full of meat, as though from here it was simpler to go out to the forest.

Alone or in groups, with or without children, small trips are made in search of many kinds of products. It is from the forest that the thatch for baskets and houses comes, as well as the resin for the tembetá lip plug, the bamboo and genipap paint for the arrows, caitetu hide to decorate them, string and wood for the bows; tucumã nuts, armadillo shells, beans and beads, hedgehog hide for the collars and bracelets, etc.

The metare is not only more connected to the forest and to the play of the expeditions, it is also the place where one prepares for and from which the festivals emerge. The festival and work appear to be intertwined, for in the metare crafted objects are produced, which are traded as presents in the festival of the Mapimaí, where the members of one half go over to the side of the other and vice-versa, in the midst of songs, dances and much drinking. This festival, which takes place in the harvest or in planting time, is when the halves exchange presents and food. In this festival one can clearly observe the division between the two halves. Months are necessary to prepare for the festival, which demands immense quantities of chicha, the traditional fermented beverage. This is an occasion of several days of complex ceremonials, when people dress up in collars, headdresses and painted cotton belts. On the day of drinking the festival beverage, an immense procession comes from the woods to the village, in ritual song and theatre. The women of the ceremonial chiefs carry fire torches, which they must not allow to burn out, for this would mean not only that they will soon die, but also that the demiurge, the creator being of humanity, Palop, ("our father") refuses to visit and protect the village.

In this combination between festival and work, the rules of the halves, forest/village, are revealed, and one can thus clarify how the work parties and festivals take place. Among the work rituals, the collective labor parties stand out, all the are, ‘companions’ being called at the end of the phase of felling the forest.

There were times, in 1979 for example, when four collective work parties happened in the same year. When a garden was cleared by a collective labor party, for example, the two halves worked together. In the morning, the whole tribe got together in the house of the owner of the garden in order for the shamans to guide them, with chants. Then, the metare and iwai halves went to the garden, one after the other. While the men got the axes, the women made the fires – each her own -, hung up the hammocks, roasted yams or corn and fed the children. All of a sudden, cries and songs in code advised them that they should move from where they were. There was a rush of people carrying children, baskets, buckets, collars. It was the sudden change, one more tree would fall. They would go higher up into the forest, relight the fires and several times the sequence would be repeated.

Cosmology and rituals

As in many societies in which shamanism has a central role in social life, questions related to health and sickness have an intrinsic relation to the supernatural universe. There are various categories of spirits that make men get sick, and there are also those that, when invoked, can avoid sicknesses or make then stay away. There are narratives associated with each one of these beings.

According to Suruí cosmology, souls should cross over a trail full of dangers. For example, a giant vulture devours them; a stone crushes them; excrement of an immense lizard buries them; a woman or man with unusually large sexual organs frightens the men or women (respectively) that approach; among many other torments. The courageous people are able to cross over the trail and arrive at an eternal and secure dwelling, together with all those who were shamans. The cowards or those who committed incest die a second time, or go on living in the villages of the useless souls. One should not pronounce the names of the dead, so that his/her soul does not come back to haunt the living, and so that he/she makes the final crossing in peace.

As far as the rites of passage, the “Young Woman’s Festival” is outstanding, an institution that is found among all the Monde groups, as well as in other Tupi groups, which marks the passage of the young girl, from the stage of infancy to adolescence upon her first menstruation, the girl having to remain secluded in a longhouse for a certain period; and the couvade, or seclusion for seven days which the parents have to comply with after the birth of their son/daughter, in which they cannot make any physical efforts nor eat certain kinds of animals.

The funeral rites are not very elaborate, but the Hoeyateim, curing rituals and the invocation of plenty, can last days and nights in succession. This festival is strongly identified with the forest, where it begins and ends. The shamans lead a circle of men with his staff in which the men hold tall bamboos, up to four meters high, where it is believed that the spirits are incorporated. Another circle consists of men playing flutes one or two meters long, where they also say that the spirits are present. In both circles, the women can dance accompanying their husbands

In order to understand the Hoeyateim, it is necessary to say that the Ho are a class of spirits. The first time the festival was held after contact was in May, 1979, after the recomposition of the metare. It was the time for gathering of yams, the beginning of the drought, and it functioned as an invocation of abundance. The Suruí said that only after that time, having gone through the great dying in the time of measles, were the gardens sufficiently large to hold the festival dedicated to the metare. That time there was no food involved, except some iatir (smaller offerings of beverages) several days before, and a distribution of game at the end of the festival. In 1980, by contrast, the Hoeyateim was made along with a iatir.

On a certain day the goanei, spirits of the rivers, are invoked, on another, goraei, spirits of the sky, which then come to the village. In each one of these classes there are multiple beings, each one with its song and telling its story. These songs, which are those that the shaman sings on curing and blowing over the sick, are known by all.

Day and night, the music, coming from the other world, makes an extraordinary tone float over the village, the same diffuse awe inspired in another village by the song of an apprentice shaman in seclusion. From afar can be seen, above the longhouses, the bamboos moving along as though by themselves, accompanied by the repetitive cadence of the flutes. In one or two of the five days, the whole population is blessed and blown over by four shamans, both in the metare and in the village, receiving sacred Stones and talismans against sicknesses. Breath (always connected to the soul) is important at the end of the festival, when everyone whistles in a circle.

On these occasions, the place of the metare was fundamental in the rituals, and it was important that the halves walk separately from the forest to the village. Long speeches united the two halves in the clearing, at the beginning and end of the festival. After that, the bamboos and flutes were thrown away or broken in the forest, and could not be played again – they went back to their origin.

The festivals today

The set of Paiter festivals are: Mapimaí (of the creation of the world), Ngamangaré (of the new garden), Weyxomaré (of painting), Hoeyateim (festival for the shaman to control the spirits of the village), Lawaãwewa (of the building of the new house), Ytxaga (of fishing with timbó).

The traditional festivals and dances have suffered many alterations, and many have, over time, come to be abandoned due to the ideological conflicts with the new religions introduced in the indigenous communities. The Mapimaí festival, for example, was held in the year 2002 after 12 years of not being held, according to the Suruí, in memory of some of their dead.

The festivals commemorated by non-indigenous society (Christmas, birthdays, civic dates, etc.) have in large part been assimilated by the Paiter.

Myths

In the Paiter narratives, aspects referring to social life, the traditional mythical universe, rites of passage, the origin of the world and other aspects of cultural life are clear. Among the various stories, we highlight the story of the Moon, which narrates the case of two siblings, who were condemned, because they practiced incest, and were transformed into the Moon, the dark side of the moon being one of the siblings.

The moon, Gatikat

It was thus as it will be told, that the moon came into being.

There was a family, from the ritual half of the íwai, those of the food, who was busy in preparing the beverage for the festival, going to gather yams in the garden to cook. In this family, there were two brothers and two sisters. One of the girls, who was very pretty, was akapeab, in seclusion because she was in her first menstruation. She would be married, as one must, with her maternal uncle, when her period of seclusion had ended.

The maternal uncle, who was from the other half of the village, that of the metareda, or from the forest – since by the fact he was from the other half he could marry her – was far away, in the clearing in the forest, making arrows and other presents that that half had to give to the food half, in the festival.

One night, a man came to the little house of the girl, lay down in her hammock and they made love. In a low voice, for no-one to hear, she asked him:

-Is it you, my uncle, that is doing this to me?

-It is I, yes, your maternal uncle...

Many, many nights he returned. When it was dark, he would always come, and he used to lay with her. The girl asked:

-Is it you, uncle?

-It is me, yes...but don’t tell anyone, only when you can leave the little house to marry.

The girl became suspicious, after awhile – was he really her uncle, this night visitor? She decided that she would smear genipap paint on his face.

At night, as she usually did, she left the little straw door, the labedog, in the back part of the house, slightly open for him to come in easily. Late that night, he came, and lay down with her in the hammock.

Oh, uncle, is it you?

Yes, it’s me!

She took the genipap and smeared it on his face. He found that strange, but she Said that it was water, to relieve the heat.

Next day, she told her mother what had been happening.

-Mother, is it really my uncle, who is making love to me every night?

No, it can’t be, my daughter, an uncle does not do that with his niece, only when seclusion ends. If it were another, then it could be...

Have you already asked if he is your uncle?

-I asked! And he told me not to tell anyone!

-Why does he want to keep it a secret? If he is your uncle, you are his wife, and not of the others, he can wait for you to come out of seclusion!

-Today I smeared genipap on his face, mother! You can go see, there in the metareda, in the forest, if it is really him!

Her mother thought it was not the uncle for the uncle would not sneak in hidden into the little house. If it was another suitor, for example a cousin, then he would try to make love to her without her uncle’s knowledge. She went to the clearing where the half from the forest was staying, during the dry season, and came back quite frightened:

-My daughter, your uncle’s face has no genipap, no painting. It is your brother’s face, here in our half, that is painted!

The girl began to cry, in deep despair:

-So it is my own brother who comes to make love to me, every night!

The mother also wept, and Said that they had to go away to the sky. The brother, guessing that he had been discovered, came forth, already bringing all of his things, his belongings, his baskets. The sister came out of the little house, putting an end to her seclusion, but without painting herself with genipap, nor adorning herself like a bride, as would be the case if she were to marry her uncle.

-Mother! Stick the arrowpoint in my body for me to die! –She asked her mother. She really wanted to die.

-No, you will not die ! – the mother answered. –You will go to the sky.

And the two siblings went up to the sky climbing up a vine. Since thenthe moon, which did not exist before, has appeared. The dark side of the moon is the brother’s face, painted with genipap.

Narrator: Dikboba (1990)

The need for protecting the children can be observed in the story of the cicada: they say that long ago children were caught stealing peanuts from the garden of the Gamep, and that, as punishment, the Gamep sewed the mouths of the children and tied them to a tree. The children screamed but no sound came out from their mouths. When it grew dark, they became cicadas. (Dikboba, 1988).

The Cicada, Nangará

A very long time ago, the Gamep planted an immense garden, full of peanuts. When the time came for harvesting, they did not stop eating, and lived making peanut makaloba, one of the kinds of fermented drink.

The children from other groups, other than the Gamep, saw how many peanuts they ate and wished to eat some. They discovered the place of the garden and got into the habit of going there to steal. They ate until they were full, and never got caught. The Gamep realized that they were being robbed and kept watch, one day, catching them in the act:

- You live by ruining our peanuts, but now you will learn once and for all to leave us in peace!

The owners of the garden sat thinking what they could do to punish the children. They decided to sew up the mouths of some of these little thieves, the younger ones, who had not succeeded in getting away in time, and tied them to a tree, with their mouths sewn up.

The poor things wanted to cry out to call their parents, but only a whispering noise came out of their throats. The owners of the garden observed them from afar, hidden.

The whole day the children who were tied up bawled to cry out, and only guttural sounds came out: "ruuu...ruuu...ruuu...".

When it began to get dark, they turned in cicadas.

Only then the adults became frightened, and with remorse.:

- Where are you going?

But it was too late. They had already gone. Because of that, today, the cicadas, nangará like to stay clinging to the trees.

Narrator: Dikboba (1988)

Proud of being a warrior people, the Paiter have a series of heroes, who are usually praised in their stories, where they tell of war and death, of the presence of the non-Indians and how these had already brought destruction and death even in the old times.

The traditional narratives are being constantly substituted by the new Christian religions, despite there being a certain resistance from some families and communities. The pajés have suffered persecution and enormous pressure from the missionaries, forcing them to abandon this tradition and age-old knowledge in the spiritual and health area.

To hear stories of pajés these days is very rare, for the non-indigenous religions and missionary presence in the area prohibit that these stories be transmitted to the younger people. Several members of the community resent this fact and constantly talk about what the Christian religions have done to their culture.

The churches which are present in the villages (through periodic visits from missionaries) are the Baptists, the Catholic, the Lutherans, and the Assembly of God.

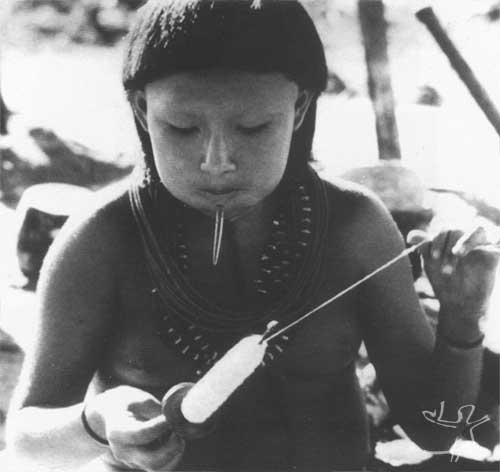

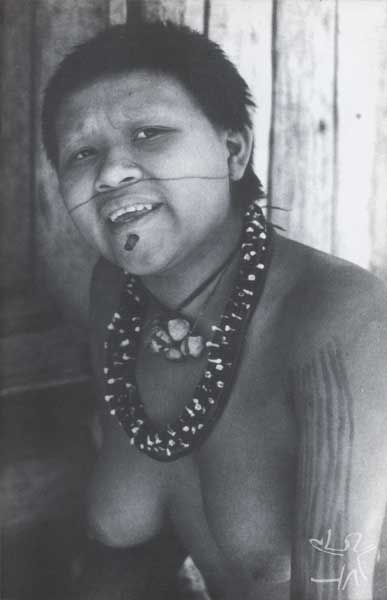

Material culture

The women produce collars using various materials, such as tucumã seeds, monkey teeth, armadillo beads and shell, hedgehog pelts and wild seeds. The tucumã nuts are broken, cut with a knife, bored, strung on a line at two points and polished with stone, sometimes measuring ten meters or more. At night, it is common for the women, generally the girls, to string the beads. They roll up the yarn, weaving the threads in a kind of crochet, the string being held by the big toe. They make hammocks, agoiab (straps) to carry the children and belts for men and women. Some of these belts and agoiab are painted with red dye and decorated with small collar strings. The looms are small and simple, these days using metal spindles, and clay whorls.

Besides the fabrics and collars, another art of the women is basketwork. There are baskets of the most diverse sizes, in which they keep objects, string, food, or the larger baskets for carrying food, hammocks, mats, fans, house-doors . There are various types of weaving, with or without red dye. To get an idea, an adô (a basket for carrying provisions from the garden), is made in less than an hour.

Amidst all this production, the great Suruí art is still dark ceramics, from the smaller pots for makaloba (a fermented drink made of manioc or corn) to the small, beautiful gourds, with a mouth or not, where cut up red caju fruits are offered with great refinement and are served from little straw spoons, or larvae. In the ceramic plates, food offerings are made, with each person waiting his/her turn. The ceramics are made with the rolling technique, burnt twice, in the village or forest. On the first burning, an oven-like container is made with the embers of the fire, covering the ceramics. On the second burning, the ceramic piece is placed over the fire face-down. Men and women go out to get clay which is of excellent quality in the territory suruí.

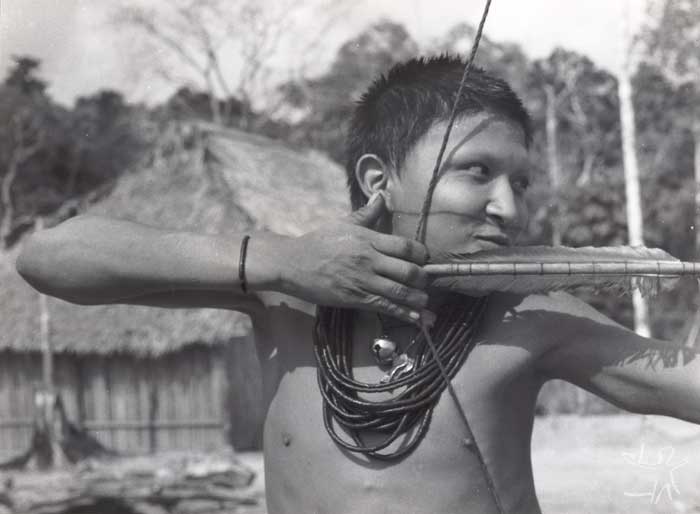

The men make objects such as arrows with difficult-to-get bamboos. They are decorated with wild pig fur, cotton painted with red dye or genipap (blue-black) designs, a dark resin being used. Every arrow has its maker who can easily be identified. Each has a shape, a design, a purpose (for hunting different animals, fishing or warfare).Another object made by the men is the betiga or tembetá, an adornment which is used in the hole below the bottom lip by men and women, made of jatobá resin dried instantly, polished and delicately smoothed for hours. There are also the mixangáp, leg-rattles, used in the festivals; headdresses, various feather adornments for the festivals; combs; headdresses of straw that must be washed, dried and painted, and the flutes for the Hoeyateim. The men paint the women with genipap in the festivals. The men make the facial tattoos and even today bore holes in the lips of seven or eight year old children.

Besides these objects, it is the men who build the longhouses, the seclusion houses and the shelters.

Productive activities

The Paiter have a great knowledge of agriculture and family gardens are cultivated by groups of brothers, in which a variety of products such as corn, manioc, potatoes, yams, beans, rice, bananas, peanuts, papaya, as well as cotton and tobacco are cultivated. The system of planting is swidden, each garden being abandoned after two years of use.

With regard to the sexual division of labor, traditionally it is up to the men to cut down the forests for the garden and to make arrows; while the women spin, make ceramics and baskets, cook, harvest and take care of the children. Men and women plant and fish.

They dedicate themselves to the gathering of fruits, honey, larvae, palm cabbage and other products of the forest. After 1981, on becoming the owners of the coffee plantations of the invaders who were expelled from their territory, they went on to sell coffee on the market. The financial income is used to buy products today considered indispensable, such as clothes, tools and food.

They are good hunters and fishers. The hunt can last hours, or a whole day, or days, or even weeks. The women like to go together and at times they take the children. Women and children wait at designated places while the men go off on the hunt properly speaking. There are various techniques of hunting, like traps and hiding-places, where the hunter imitates the sound of several animals until they respond to his calls. Hunting is preferentially done with firearms, for they claim that bamboo is difficult to find these days.

After the hunt, the meat, the smoked fish and the fruits are distributed according to the degree of kinship.

The most prized game are the wild boar, the armadillo and, for the women with newborn children, the partridge (various species of birds of the Timanideus family, which are highly appreciated). They also eat curassow, wild pig, jacu, anteater and several types of monkey, and especially prefer the coati. There are, however, several species of monkeys that are the object of food taboos, such as the jaguar, the turtle, the tapir, the alligator, and, for the Gamep, the deer and the cutia (but these days the cutia is consumed, as well as the paca, which is no longer the object of food taboos). The deer, the anteaters and the tapirs are especially prohibited to the children (the latter two also being interdicted for the young men). The trumpeter is only permitted to the elderly people. The Paiter also do not eat any reptile or amphibian, nor eagles, rats, bats, ducks, socós, tucanos and capybaras.

According to the survey made by the NGO Kanindé, the fish consumed by the Paiter are those with scales, since those with skin are considered vectors of sickness. Only the electric eel can be utilized, since it is considered a special kind of fish. The principal rivers that contain fish and that are used by the Paiter community are the: Branco River, the Lobó River, the Gapó River and the Ribeirão River. Small streams near the villages are used, mainly by the children, for fishing with bow and arrow. The use of fish poison is also a traditional method of fishing in the period when the riverbeds are dried up. The hook, nylon lines and fishing nets were introduced and today are the most common methods of fishing.

There is an aquaculture unit in the village of Lapetanha. The building of a dam, a tank (300 m²) and the purchase of tambaqui fishlings (3.000) were the result of a pilot project (which includes aquaculture, cattle-raising, agroforestry management and “white” farming) done by the Paiter association Metareilá, with financing from the Ministries of Agriculture, Supplies, and Agrarian Reform.

Gardens

Cooperation in the garden involves various rules among the Paiter lineages. The identification between labor and social organization is expressed when the whole longhouse population goes off together to the garden; or by the obligation of each man to offer several days of labor to his non-co-resident kin. Thus, married brothers help each other out when they live in different houses; sons-in-law help their fathers-in-law; brothers-in-law go to the garden of their sister’s husband, their potential father-in-law.

The rules for cooperation are extremely varied. For example, the chief of a longhouse goes to gather with his classificatory sons, even though only one of them lives in his longhouse. Why does the married son who lives in another longhouse go with him instead of going to gather with his co-residents? It’s because part of a lineage is preparing a iatir (offering of beverage or soup to other houses). The rule is that one of the men of the house, who is from another lineage, married with the classificatory daughters of the longhouse chief, not be present. It is the time of the rains and corn and the iatir is called meeg-aré: the "collective corn work party", "companion of the corn". Áre is the word that is used for the brothers; áre and aré can be thought of as variations on the same word, showing that the collective work party is a lineage matter (brothers belong to a same lineage). One only needs to observe that all the words for collective work parties refer to brothers: meeg-aré, sogai-aré (planting work party), gã manga aré (work party for making a garden, for cutting down the trees), soe-karé (hunting work party).

Coffee

The first experience of the Paiter with coffee cultivation occurred after the removal of the colonists in 1981, when these left many behind many coffee plantations inside the indigenous land. These plantations were located in the areas all along each line (roads) of the Incra colonization project, extending inside the reserve. The Paiter organized themselves by extended families to take care of the coffee plantations, taking advantage of the harvests of 1982 and to protect their territory from new invasions. Thus, villages were established on lines 08, 09, 10, 11 (four villages) , 12, and 14 (two villages).

The Paiter went on to take care of the coffee plantations and to commercialize this product, which at the time brought in a good return for them and thus they were introduced into the market economy. In the years that followed, however, coffee suffered a drastic decline in price and this discouraged the Paiter from continuing to cultivate. Many coffee plantations were abandoned. In the ‘90s, coffee once again was sold at a quite high price, which stimulated the Suruí to go back to cultivating. Today, in the villages that don’t exploit lumber, coffee cultivation is the main income-raising activity. These coffee gardens are family properties, however not all families have a plantation.

Part of the coffee produced is processed in the district of Riozinho, municipality of Cacoal, in the pounding machine that the Funai allows the Metareilá to use. The other part of the production is sold directly by the indigenous families to the processing companies. After processed, the coffee is sold in the city of Cacoal, generally without the presence of the Funai

Cattle-raising

In almost all the villages there is extensive cattle-raising. Several villages have corrals with tile roofs and cement floors and others don’t. The herds are small and belong to each family, varying from a few head to scores of cattle which are used for milk production for consumption and for sale on the meat market.

Metareilá organization

Despite all of the difficulties, in 1988, the indigenous leadership led an attack against the lumbermen and created the Metareilá Organization of the Paiter Indigenous People. The organization seeks to expel the lumbermen from the Indigenous Land, remove the leadership that sells lumber and choose leaders who are committed to environmental defense. This has not been an easy decision, as it has meant having less money and “benefits” to which they have become accustomed. They have gone on to defend, together with other indigenous peoples of the state, the preservation of natural resources, making public declarations in newspapers against the illegal sale of lumber.

From 1988 to 1990 lumber was not sold without the connivance of the Paiter. However, from 1991 on, with no support for their activities and with no resources to attend the needs of the communities, the Metareilá lost their power and several leaders went back to making accords with the lumbermen.

Even so, the Metareilá has sought a solution for the problems of the Paiter and continues to defend the conservation of natural resources. The Organization has sought to keep up with the execution of government projects, such as the PLANAFLORO (Sócio-Economic and Ecological Plan for the state of Rondônia ) and the Úmidas Project (Humid Agenda – Planning program for the year 2021) as well national and regional policies on health, education, land, and other subjects that have to do with the indigenous question. This has demanded efforts and mainly resources, which were taken out of the pockets of the directors, which often has brought many difficulties of follow-up due to lack of money, travel, food, and lodging.

The participation of the Paiter in following-up on the PLANAFLORO was decisive in guaranteeing that they presented projects to the Program for Support to Community Initiative. In the execution of these projects, however, the Paiter have faced difficulties due to the fact of their not having financial-administrative experience and not having efficiency in technical assistance.

Despite all these difficulties, the Metareilá has sought to provide incentive to the traditional economy and environmentally sustainable alternatives. To do that, they have sought to articulate with national and international indigenous organizations, but they have been more than aware of their lack of technical capacity for elaborating projects and administering resources.

The Paiter have made partnerships with state and municipal organizations and non-governmental organizations. Among the principal partners are the PACA (Cacoal Environmental Protection), which for years has been training indigenous health agents, building Health Posts in the villages and contributing to cultural recovery; the Prefecture of Cacoal, which has been supportive by providing teachers in the villages; recently the KANINDÉ (Association for Ethno-environmental Defense), which has assisted in the formulation of projects.

In 1999 the indigenous community of Line 14 created another organization, called the "Gamir Association".

In several villages, the Pamaur, Panhamasodér, Pamakoy APP (Teachers’ and Parents’ association) were created, dedicated exclusively to indigenous education.

In 2003 the Suruí Forum of Indigenous Organizations was created.

The Paiter women have been mobilizing to form an association, with the support and incentive of the Metareilá Association.

Health and education

Up to 1989, it was the Funai, through its Executive Administration of Cacoal, which provided health assistance to the Paiter population. In the period from 1989 to 1991, the Health Assistance Project for the Suruí Paiter people developed by the CERNIC (Centre for Child Neurological Rehabilitation of Cacoal) in accord with the IAMÁ (Institute for anthropology and the environment), and with financial support from the Norwegian Program for Indigenous Peoples of the NORAD ( Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation), was successful in taking the first steps to improving the low level health assistance to the Suruí.

In continuity with this work, the PACA (Cacoal Environmental Protection) has been developing health actions with indigenous populations since 1992 through the training of Indigenous Health Agents, the results of which has diminished the high mortality rate and has made a significant population increase possible.

The research done in the villages has shown that the sicknesses and health problems that most affect Paiter children are: verminosis, influenza, pneumonia, dehydration and diarrheia. Among adults, the most common sicknesses are: flu, pneumonia, rheumatism and tuberculosis.

There are health posts on the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land, except in two villages of line 11(Lobo village and Amaral village) and in one of the two villages of line 14 (Placa village). Transportation used to get out of the villages and to get medical attendance in the Indigenous Health house in Riozinho, or in the public health network of Cacoal, is provided by the vehicles and drivers of the Funasa. On three Indigenous Posts - Line 11(Lapetanha village), Line 14(Gamir village) and e Line 09 – transceptor radio systems have been installed by the Funasa/PACA in order to cover emergency health needs.

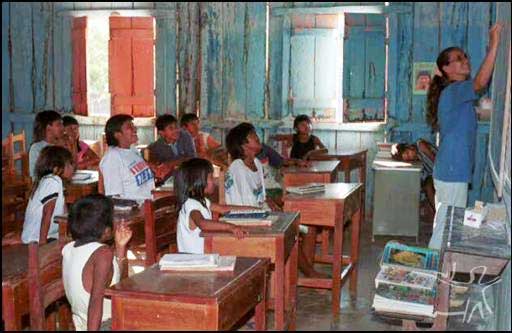

With regard to education, from 1992 to 1996 the IAMÁ coordinated a project for educating indigenous teachers, which included teaching of the native language and Portuguese, as well as literacy in the indigenous language.

Currently, the schools of the villages have bilingual instruction from the 1st to 4th grades. The teachers in the villages are from the municipal school network of Cacoal. The indigenous teachers are hired by the state. The infra-structure of the village schools generally is improvised in various types of dwellings. Generally the schools have wooden walls, polished cement floors and asbestos roofs. In the villages that do not have schools the students study in neighboring villages.

The school lunch is provided by the SEDUC (State Secretary of Education/RO), through the regional delegacy in Cacoal. This service has been continuous which has meant a better performance on the part of the students. The preparation of the meals is voluntary and is done every day in a house by a student’s mother.

Notes on the sources

This entry on the Suruí Paiter was elaborated on the basis of a joint effort of the Metareilá (Metareilá Organization of the Paiter Indigenous People), the Kanindé for Ethno-environmental Defense and the anthropologist Betty Mindlin. Each one of the collaborators contributed from their experiences among the Paiter, so that the group would be presented here in the best way possible.

The reference works by Betty Mindlin are her doctoral thesis The Suruí of Rondônia (1984), as well as a later publication We Paiter: The Suruí of Rondônia (1985), which basically consists of a book version of her thesis. The myths that are presented in this entry were taken from the book Vozes da Origem [Voices from the Origin], estórias sem escrita [unwritten stories] (1996) organized by Betty Mindlin along with several Suruí narrators. This book contains a considerable collection of Suruí mythic narratives which cover the most diverse aspects of their culture.

Besides the works by Mindlin there is the noteworthy contribution of the Kanindé (Association for Ethno-environmental Defense) with its project Paiter Ethno-environmental Diagnosis, in which there is a component on participative Agro-environmental Diagnosis. This work consists of research done by this NGO in partnership with the Metareilá organization, and does a survey of the present situation of the indigenous people and the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land. The data on agronomical projects, the indigenous association movement and the “state of the art” of the institutions were taken from this report.

Besides this report, Paiter leaders have revised and offered their contributions to all parts of this text.

Sources of information

- ALTMANN, Lori; ZWETSCH, Roberto. Paíter : o povo Suruí e o compromisso missionário. Chapecó : s.ed., 1980. 128 p.

- --------. Projeto de educação para o grupo Suruí, Rondônia. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da (Coord.). A questão da educação indígena. São Paulo : Brasiliense ; CPI-SP, 1981. p.44-50.

- BONTKES, Carolyn. Subordinate clauses in Surui. In: FORTUNE, D. L. (Ed.). Porto Velho workpapers. Brasília : SIL, 1985. p. 189-207.

- BONTKES, Carolyn et al. Paiter Koe Tig 1, 2, 3, 4. Porto Velho : SIL, 1993. 28, 37, 44 e 25 p. Circulação restrita.

- -------- (Comp.). Vamos diminuir 1, 2. Porto Velho : SIL, 1993. 44 e 32 p. Circulação restrita.

- -------- (Comp.). Vamos somar 1, 2, 3. Porto Velho : SIL, 1993. 36, 32 e 22 p. Circulação restrita.

- --------; MERRIFIELD, William R. On Surui (Tupian) social organization. In: MERRIFIELD, William R. (Ed.). South American kinship : eight kinship systems from Brazil and Colombia. Dallas : The International Museum of Cultures, 1985. p. 5-34.

- BONTKES, William. Dicionário preliminar Suruí/Protuguês-Português/Suruí. Porto Velho : SIL, 1978.

- --------; DOOLEY, Robert A. Verification particles in Suruí. In: FORTUNE, D. L. (Ed.). Porto Velho workpapers. Brasília : SIL, 1985. p. 166-88.

- CHIAPPINO, Jean. The Brazilian indigenous problem and policy : the Ariuanã Park. IWGIA: Document, Copenhagem : Amazind ; Genebra : IWGIA, n. 19, 1975.

- COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares. Estudos de ecologia humana entre os Suruí do Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia : Aspectos alimentares. Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 2, n. 1, p. 57-87, 1985.

- --------. Estudos de ecologia humana entre os Suruí do Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia : Elementos de etnozoologia. Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 2, n. 1, p. 9-36, 1985.

- --------. Estudos de ecologia humana entre os Suruí do Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia : plantas de importância econômica. Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 2, n. 1, p. 37-55, 1985.

- --------. Estudos de ecologia humana entre os Suruí do Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia : O uso de larvas de coleópteros (bruchidae e curculionidade) na alimentação. Rev. Brasileira de Zoologia, São Paulo : s.ed., v. 2, n. 2, p. 35-47, 1984.

- --------. From shifting cultivation to coffee farming : the impact of change on the health and ecology of the Suruí indians in the Brazilian Amazon. Bloomington : Indiana University, 1989. 392 p. (Dissertação de Ph.D)

- --------. A habitação Suruí e suas implicações epidemiológicas. In: IBÁÑEZ-NOVIÓN, Martin; OTT, Ari M. T. (Eds.). Adaptação à enfermidade e sua distribuição entre grupos indígenas da bacia Amazônica. Brasília : Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas em Antropologia Médica ; Belém : MPEG, 1985. p. 120-38.

- -------- et al. Hepatitis B epidemiology and cultural practices in Amerindian populations of Amazonia : the Tupi-Monde and the Xavante from Brazil. Social Science and Medicine, s.l. : s.ed., v. 42, n. 12, p. 1738-43, 1996.

- -------- et al. Paracoccidioidin an histoplasmin sensitivity in Tupi-Monde Amerindian populations from Brazilian Amazonia. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Liverpool : s.ed., v. 88, p. 197-207, 1994.

- --------; MELLO, Dalva A. Enteroparasitoses e Capillaria sp. entre o grupo indígena Suruí, Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro : Instituto oswaldo Cruz, v. 76, n. 3, p. 299-302, 1981.

- COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares; SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura. Avaliação do estado nutricional num contexto de mudança sócio-econômica : o grupo indígena Suruí do Estado de Rondônia, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 7, n. 4, p. 538-62, out./dez. 1991.

- --------. Bicudo das palmacéas : praga ou alimento? Ciência Hoje, Rio de Janeiro : SBPC, v. 16, n. 95, p. 59-60, nov. 1993.

- --------. Inexistência de infecção por Piedraia hortae entre o grupo indígena Suruí, Rondônia. Rev. da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, Brasília : Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, v. 23, n. 2, p. 125, 1990.

- --------; TANUS, Ronan. Estudos epidemiológicos entre grupos indígenas de Rondônia. I: piodermites e portadores inaparentes de Staphylococcus sp. na boca e nariz entre os Suruí e Karitiana. Rev. da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, Brasília : Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, v. 27, n. 1, p. 13-9, 1985.

- COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares.; SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; INHAM, T.M. Estudos epidemiológicos entre grupos indígenas de Rondônia. II: bactérias enteropatogênicas e gastrenterites entre os Suruí e Karitiana. Rev. da Fundação SESP, Rio de Janeiro : Fundação SESP, v. 30, n. 2, p. 111-9, 1985.

- COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares.; SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; VALLE, Antônio C. F. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tupi-Monde Amerindians from Brazilian Amazonia. Acta Trópica, Basiléia : s.ed., v. 61, p. 201-11, 1996.

- FLEMING-MORAN, Millicent; SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares. Blood pressure levels for the Surui and Zoro indians of the Brazilian Amazon : group and sex-specific effects due to altered body composition and diet. Human Biology, Detroit : Human Biology Council, v. 63, n. 3, p. 835-61, 1991.

- FREITAS, Laura Eugenia Perez. Changement social et sante chez les Tupi-Monde de Rondonia (Bresil). Paris : Université de Paris X, 1996. 126 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- IAMÁ. Paiter Koetig Na II. São Paulo : Iamá, 1993. 35 p.

- JUNQUEIRA, Carmem; LIMA, Abel; LAFER, Betty. Terra e conflito no Parque do Aripuanã : o caso Suruí. In: SANTOS, Silvio Coelho dos (Org.). O índio perante o direito : ensaios. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1982. p.111-6.

- MEER, T. H. der. Fonologia da língua Suruí. Campinas : Unicamp, 1982. (Dissertação de Mestrado).

- --------. Ideofones e palavras onomatopaicas em Suruí. Estudos Lingüísticos, Araraquara : s.ed., v. 7, p. 10-5, 1983.

- --------. A nasalização em limite de palavra no Suruí. Estudos Lingüísticos, Araraquara : s.ed., v. 4, p. 282-7, 1981.

- MINDLIN, Betty. Amor e ruptura na aldeia indígena. In: PORCHAT, Ieda (Org.). Amor, casamento e separação. São Paulo : Brasiliense, 1992.

- --------. O aprendiz de origens e novidades : o professor indígena, uma experiência de escola diferenciada. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo : USP, v.8, n.20, p.233-53, 1994.

- --------. Comunitário ou coletivo : um caso tribal. Revista de Administração de Empresas, São Paulo : s.ed., v.24, n.3, p.87-92, jul./set. 1984.

- --------. Iabadai Surui will not forget how the lumbermen killed iabner. IWGIA: Newsletter, Copenhagen : IWGIA, n.58, p.21-31, ago. 1989.

- --------. Medicina indígena e assistência médica : comentário sobre o Projeto de Saúde Suruí de Rondônia. Boletim da ABA, Florianópolis : ABA, n.14, p.9-11, jan. 1993.

- --------. Nós Paiter : os Suruí de Rondônia. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1985. 226 p.

- --------. Os Paiter : vinte anos depois. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 437. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- --------. Peixoté, a casa dos espíritos. Bric a Brac, Brasília : s.ed., s.n., p.55-6, dez. 1990.

- -------- (Apresentadora). Primeira declaração Suruí. Cadernos de Opinião, Rio de Janeiro : Paz e Terra, n.15, dez. 1979/ago.1980.

- --------. Professores indígenas ensinam nas aldeias. Boletim da ABA, Florianópolis : ABA, n.14, p.4, jan. 1993.

- --------. The Suruí. Cultural Survival: Occasional Paper, Cambridge : Cultural Survival, n.6, p.53-4, out. 1981.

- --------. Os Suruí de Rondônia. São Paulo : PUC-SP, 1984. 246 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Os Suruí de Rondônia : entre a floresta e a colheita. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, n.27/28, p. 203-11, 1984/1985.

- --------. Unwritten stories of the Surui indians of Rondônia. Austin : Institute of Latin American Studies, 1995. (Ilas Special Publication)

- --------. A vida dos Suruí em Rondônia e a luta contra os invasores. Porantim, Brasília : Cimi, v.7, n.75, p.8-9, mai. 1985.

- --------. Vozes da origem, estórias sem escrita : narrativas dos índios Suruí de Rondônia. São Paulo : Ática/Iamá, 1996. 218 p.

- --------; TRONCARELLI, Maria Cristina; SEKI, Lucy (Orgs.). Paiter Koetig Na I. São Paulo : Iamá, 1991. 50 p.

- NASCIMENTO, Eloíza Elena della Justina Nascimento (Coord.). Paiter, gente de verdade : diagnóstico agro-ambiental participativo. Cacoal : Organização Metareilá do Povo Indígena Suruí, 2000. 97 p.

- PUTTKAMER, W. Jesco von. Brazil protects her Cinta Largas. National Geographic Magazine, Washington : s.ed., v. 140, n. 3, p. 420-40, 1971.

- SALZANO, Francisco Mauro et al. Protein genetic studies among the Tupi-Monde indians of the Brazilian Amazonia. American Journal of Human Biology, New York : s.ed., v. 10, p. 711-22, 1998.

- SANTILLI, Marcos. Àre. São Paulo : Sver & Boccato, 1987. 168 p.

- SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura. Coping with change in native Amazonia : a bioanthropological study of the Gavião, Suruí, and Zoró, Tupi-Monde. Speaking societies from Brazil. Indiana : Indiana University, 1991. 269 p. (Dissertação de Ph.D.)

- --------. Dermatóglifos digitais e distribuição espacial dos Suruí, Parque Indígena Aripuanã, Rondônia : análise estatística univariada. Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 5, n. 2, p. 104-11, 1989.

- --------; COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares. Contato, mudanças socioeconômicas e a bioantropologia dos Tupí-Mondé da Amazônia brasileira. In: SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares. (Orgs.). Saúde e povos indígenas. Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, 1994. p. 189-211.

- --------. On the (un)natural history of the Tupi-Monde indians : bioanthropology and change in the Brazilian Amazon. In: GOODMAN, A. H.; LEATHERMAN, T. (Eds.). Building a new biocultural synthesis : politicas-economic perspectives on human biology. Ann Arbor : Univ. of Michigan Press, 1998. p. 269-94.

- --------. Socioeconomic differentiation and body morphology in the Surui indians from the Brazilian Amazonia, Chicago : s.ed., v. 37, n. 5, p. 851-6, 1996.

- --------. Socioeconomic transition and growth of Tupi-Monde Amerindian children of the Aripuana Park, Brazilian Amazonia. Human Biology, Detroit : Human Biology Council, v. 63, n. 3, p. 795-819, 1991.

- SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos Everaldo Alvares; LINHARES, Alexandre C. Estudos epidemiológicos entre grupos indígenas de Rondônia. IV: inquérito sorológico para rotavirus entre os Suruí e Karitiana. Rev. de Saúde Pública, São Paulo : s.ed., v. 25, n. 3, p. 230-2, 1991.

- SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; MEIER, Robert J.; VIEIRA FILHO, João P. B. Digital dermatoglyphics of three amerindian populations of the Brazilian Amazonia : a further test of the field theory. Annals of Human Biology, Londres : s.ed., v. 17, p. 213-6, 1990.

- Paracoccidioidomicose entre o grupo indígena Suruí de Rondônia, Amazônia (Brasil). Rev. do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, São Paulo : Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo, v. 33, p. 407-11, 1991.

- Suruí Paiter Marewá. São Paulo : Memória Discos e Edições Ltda., 1985. Disco feito por Marcos Santilli, Marlui Miranda e Betty Mindlin. (Acompanha texto etnológico escrito por Betty Mindlin).

- PUCCI, Magda D. A arte oral Paiter Suruí. Tese de mestrado em Antropologia. PUC-SP, 2009.

- PUCCI, Magda. Aspects Of Paiter Suruí Oral Art. In: Vibrant, vol. 8 n. 1, 2011. Virtual Braz. Anthr. [online]. 2011, vol.8, n.1, pp. 411-426. ISSN 1809-4341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1809-43412011000100015.