Panará

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- MT 704 (DSEI, 2022)

- Linguistic family

- Jê

Despite the trauma of contact with Brazilian society in 1973, the white men’s diseases that almost decimated them, and twenty years of forced dislocation from their traditional lands of Peixoto de Azevedo River to the Parque Indígena do Xingu, the Panará have been able to recover their joy and desire to fight. They are once again growing in numbers and proud of their way of life. They were also able to take back part of their ancient traditional territory along the Iriri River (495,000 hectares of dense forest and headwaters, unspoiled by the white man) located on the border of Mato Grosso and Pará states. Nowadays, they want to be known by their real name: Panará.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

Who are the Panará?

The Panará are the last descendants of the Southern Cayapó, a large group that dwelled over a vast area in central Brazil in the 18th century. Their territory stretched from the northern part of São Paulo state, Triângulo Mineiro and the southern portion of Goiás state to eastern part of Mato Grosso state and eastern and southeastern Mato Grosso do Sul state. The Southern Cayapó were known for their “ferocity” because they took no prisoners in battle.

The intensification of mineral exploration during the 18th century increased the trade flows between the states of São Paulo and Goiás, right in the middle of their land. Realizing the potential problems this would cause, the administrations of both provinces hired frontiersmen to drive the Indians away from the travelers’ and miners’ routes. Likewise, when Bartolomeu Bueno da Silva discovered gold in the Vermelho river region in Goiás in 1772, the Southern Cayapó began to encounter non-stop conflicts along this ever-expanding frontier.

The conflicts between the Southern Cayapó and the Portuguese settlers in the Goiás region were numerous and bloody. In the first skirmishes, according to a chronicler of the time, one thousand Cayapó were captured during a three-month campaign. A different investigator calculates that another 8,000 were enslaved in these first wars. Following the second half of the 18th century, the bandeiras (early exploratory expeditions) that had organized raids against the Cayapó veered from their initial purpose of enslaving the Indians to killing all men who could take up arms. By the end, the war against the Cayapó consisted of slaughter and compulsory living under the white man’s rule.

In the 19th century the occupation of the lands southwest of Goiás compounded the conflicts with the Indians and drove the Cayapó population to near extinction, with only a few groups remaining in the Triângulo Mineiro. The Southern Cayapó were considered extinct by the first few decades of the 20th century. The Panará who did not submit to the white man’s rule and assimilation in the 18th and 19th centuries fled west and north, deep into the woods of northern Mato Grosso. What is known from ethno-history is that by the beginning of the 20th century, the present Panará came to the Peixoto de Azevedo watershed, a right-bank tributary to the Teles Pires River that is one of the feeders of the Tapajós River. The natural wealth of the region contributed towards their settling down in this location.

The Panará’s oral tradition has it that they came from the East, from a savanna region, inhabited by extremely wild and ferocious white men who had fire weapons and who fought tirelessly to kill off many Panará ancestors. According to chieftain Akè Panará, "The elders told us that, long ago, the whites killed many Panará with their rifles. They came to our villages and killed many. ‘If they ever come here,’ they said, ‘kill them dead with your war clubs, for they are vicious.’"

Why are they called "giant indians"?

The Panará stepped back into Brazilian history in the 1970’s. Nobody knew what they called themselves. It was “giant Indians,” or Krenacore, Kreen-Akore, Kreen-akarore, Krenhakarore, or Krenacarore – variations of the Kayapó name kran iakarare, which means “round-cut head,” a reference to the traditional haircut that is typical of the Panará. In extensive reports from the time of contact, there is an underlying concern with explaining their unknown origin. Calling them giants, or white Indians or black Indians, was a way of identifying them while removing them from the disturbing state of absolute otherness.

There were various reasons for this reputation, which, after contact with the Villas-Boas brothers, proved to be unfounded. Of course there were some who were very tall, but most Panará were more or less the same height as other indigenous groups such as the Kayapó or the Xavante. On the other hand, their enormous bows and war clubs, which stood 6 feet on end, impressed the whites and led them to suppose that they could be handled only by enormous men. The Kayapó, traditional enemies of the Panará, also spun tales of the giant Indians to increase the value of their own battles against their foe.

There was one documented case. Mengrire stood 6 feet 8 inches (2.03 m) tall. He was a Panará Indian who had been abducted from his village while still a child and raised by the Kayapó Metuktire (the Txukarramãe). He was later taken to the Xingu Indigenous Park where he died or was killed in the 1960’s at the age of 38. Mengrire, a real giant, was the only such Panará measured and recognized as such by medical doctors and researchers.

Besides this sole proof, Orlando Villas-Bôas tells that at the time of contact there were at least eight giants among the Panará. However, they died from white men’s diseases. Panará’s adults who lived in the Peixoto de Azevedo River area prior to 1973 are absolutely emphatic about the existence of “veeerry tall” kinfolk in the past.

When the Panará relocated to the Xingu Park on January 12, 1975, a team from the Paulista Medical School examined 27 of the 29 newcomers who were 20 years or older. The average height was 5 feet 7 inches (1.67 m), in line with the Jê group standards, a bit taller than the Upper Xingu Indians. But there was no phenomenon there.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

History of contact

When the Panará saw an airplane for the first time, flying over Sonsênasan Village in 1967, they called it the pakyã’akriti, or “phony shooting star.” They rushed to their bows and tried shooting down the intruder, but none found their mark. Inside the plane, frontiersman Cláudio Villas Bôas instinctively ducked when he saw the arrows flying by. He was on a reconnaissance mission to locate the ‘giant Indians’ in order to pacify them before contact was made with the whites in the Peixoto de Azevedo River area. He had found them at last but he had misgivings. Despite the desire to avoid the worst, he knew he was the herald of a fate that was impregnable to the warriors’ arrows. Just like a falling star, the airplane entered the life of the Panará as an omen – and would change it forever.

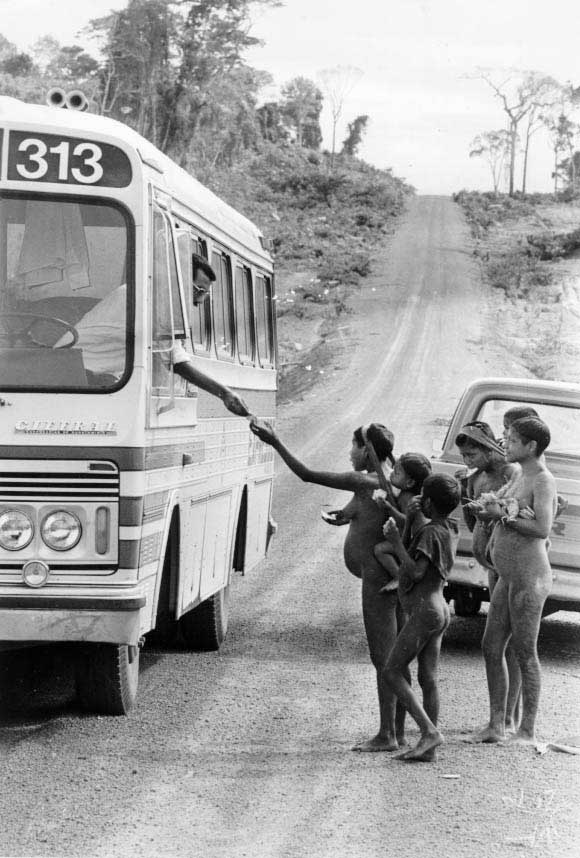

The Indians set up and broke camp quickly, always fleeing from contact. On February 4, 1973, more than five years after the initial sighting, the Villas-Bôas brother could finally approach the aloof Panará However, before this historical contact, the Panará came in sporadic contact with the white highway workers and their diseases as they built the Cuiabá-Santarém road right through Panará land. In two years, the group was almost decimated due to deaths from flu and diarrhea. “We were in our village,” Chieftain Akè Panará recalls, “and everybody began to die. Others went deep into the woods and died there. We were sick and weak, and couldn’t bury our dead. They rotted on top of the ground. The buzzards ate them all.”

Because of this tragedy, another ‘phony shooting star,’ flown by the Brazilian Air Force, airlifted the survivors from the Peixoto de Azevedo River area to the Xingu Indigenous Park, 250 km westward. Within two years, the Panará were essentially decimated, de-structured, and evicted from their native land. Within one hour, they were flown into another world. In Xingu, they lived like ghosts, roaming the county. They shifted village sites seven times, always seeking a place similar to their original territory. It was much worse than an exile.

Twenty years after that memorable trip, the Panará returned. Once again they flew in a phony shooting star, but this time back to the Peixoto de Azevedo River. From the sky, they spotted a pristine chunk of their land, still covered with forests, and preserved from prospectors, squatters, loggers and cattle. They moved back, set up camp and built a new village. They filed suits in court, and convinced the National Foundation for the Indian to support their cause. Finally, they got their land back. The “Miracle Victims” became “Subjects of History.” This is the true story of the giant Indians – the story of a giant heart.

Return to their tradicional land

While living in the Xingu, the Panará ceaselessly stressed that their current condition was but a shadow of their true society as it was in their traditional land, the Peixoto de Azevedo River area. Yet, there is evidence that the present situation was not merely a result of contact. Every formal speech delivered by the elders in the village yard, especially by the chieftains, starts with the explicit assumption that those who are speaking (the elder, the chieftain) know everything, and those who are listening (the youngsters) know nothing. Those who had heard the ancestors always delivered the formal speeches to those who had not seen or heard the ancestors. There is always an exhortation to encourage “those of now” (kômakyara), who live today, to follow the model of the ancestors, “those of before” (suankyara), who were more generous, harder-working, happier, stronger, more beautiful, less egotistical, less gossiping and less slothful.

The comparison between their life today and the life of their ancestors is a recurring them in the Panará discourse. The impression is that the Panará live under a feeble reflection of their past. This is a characteristic of the relation between elders and youngsters, ancestors and descendents in general. This present-day inferiority complex helps us understand their willingness to rebuild their society following their twenty-year-long catastrophe.

This willingness to rebuild along with the limitations imposed by the Xingu Park borders prompted the Panará to undertake the process of returning to their ancient homeland. In October 1991, six Panará and six whites boarded a bus for the historical trip back to the Peixoto de Azevedo. This was the first time the Panará returned to their region since their relocation in 1975. The group arrived in the city of Matupá, on BR-163, in the very north of Mato Grosso, and began to identify their territory.

The Peixoto de Azevedo River Valley was a desolate sight. Prospectors and farmers had cut down the forest, and polluted and silted the rivers, especially the Braço Norte. Many troughs had become marshes. Vast stretches of paradise-like Peixoto de Azevedo had turned to muck. The Indians were aghast at the effects of random cutting, cattle breeding and twenty years of prospecting. Then and there, they reported their desire to meet immediately with the authorities responsible for the construction of the highway that had instigated the occupation of the region. They were indignant and demanded a response.

During the same trip, the Panará flew over their territory. They observed that out of the eight villages that existed in 1968, prospectors, settlement or cattle breeding had destroyed six of the villages. Thus arose the idea of claiming indemnity for the occupation and destruction of their lands. On the same flight, they were able to identify a stretch of territory near the Cachimbo Range and Iriri River springheads that was still covered with pristine forests and small-flow rivers. They had located a part of their land that had not been occupied.

Back in their village, the Panará discussed among themselves what they had seen, identifying the traditional area that had not bee occupied and coming to a consensus regarding this intended area. The Panará decided to forego a major part of their traditional territory, to which they were entitled by law, in order to avoid conflicts with the whites. They claimed the area without effective occupation: 448,000 hectares spanning the Iriri and Ipiranga springheads, and the border between Pará and Mato Grosso that includes the plot of land belonging to the INCRA, in Mato Grosso. In March 1993, the Panará formally requested the demarcation of their lands.

The return

By November 1994, the Panará met with the Xingu Park leaders in the Arraias River village to present and discuss their plan to return to their original territory. It was an historical meeting, lasting for three days. Many key players in the giant Indians’ saga were present: kayapó txukarramãe chieftain Raoni; his nephew and then-director of the Park, Megaron; chief of Funai’s Diauarum Station and Kayabi leader Mairawe, and kayabi chieftains Prepuri and Cuiabano. Cláudio and Orlando Villas Bôas were also invited but could not be present. For the first time ever, all Xingu leaders met in the Panará village.

Four Panará elders and chieftains, Akè, Teseya, Kôkriti and Krekõ, declared publicly and vigorously their intention of returning to the land of their forefathers, to the Peixoto de Azevedo River area. They emphasized that the Xingu was not the Panará land and that their land was fertile and teemed with game. Nine male and female Panará delivered speeches defending the return to their land. One young Panará member spoke against the move. Most leaders who had been invited to the historical meeting spoke in support of the initiative. Many others, such as the leaders of the Txikão, Suyá and Kayabi, took the opportunity to speak longingly of the lands they, too, had left behind when they came to live in the Xingu Park. Olympio Serra, who succeeded the Villas Bôas brothers as Park manager, recalled that the original intention of the Park, had it been created as such, would have been a much larger area which would have included and protected the original lands of the Panará, the Txikão and the Kayabi. If that had been the case, it would have been unnecessary to transfer these groups to inside the Park’s present borders. The conference of the Xingu leaders in the Arraias village crystallized the Panará’s decision to return to the Peixoto de Azevedo.

In December 1994, Funai completed the identification and delimitation process of the Panará Indigenous Land. In the same month, the Panará filed a suit for indemnity of material and moral damages in the 7th Federal Court in the Federal District. The suit was initiated by lawyers from the Indigenous Rights Nucleus against the Federal Union and Funai demanding payment for damages and indemnity “to be computed at sentence.”

Between 1995 and 1996, the Panará gradually moved to a new village, which they called Nãsẽpotiti, the Panará name for the Iriri River. In September 1996, the village already hosted 75 individuals, eleven lodges, one Funai station and a passable landing strip. Those who remained in the Xingu could only think about the upcoming move since they had to wait until the fields that had been planted in the Iriri River prospered. Only then could they ensure the sustenance of the 174 individuals. Once again in their territory, the Panará could feel their pride.

On November 1, 1996, the Justice Minister declared the Panará Indigenous Land a “permanent indigenous possession,” comprising of 495,000 hectares in the municipalities of Guarantã (MT) and Altamira (PA). The same ruling chartered Funai to provide the physical demarcation of the territory, driving stakes to mark the area. The government politically recognized the rights of the Panará and their boundaries. The President of Brazil signed a decree ratifying the demarcation of the Panará Indigenous Land. It was then registered with the real estate notary offices in Guarantã and Attamira. In addition, it was registered with the Federal Union Property Secretariat in Brasília.

It is important to remember that the return to Iriri is a long-term process. The Panará know that there will be obstacles and risks along the way. They traded the security of the Xingu Park for the instability of an area open to predatory, random economic expansion. They are willing to pay the price in order to make a home in their traditional territory. It is this power that enables the 250 individuals to survive so many ordeals. In the end, the story of the giant Indians proves that there is truth in the myth. Not the one of stature, but the one of the heart. The heart of the Panará giants.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

Social space and relations

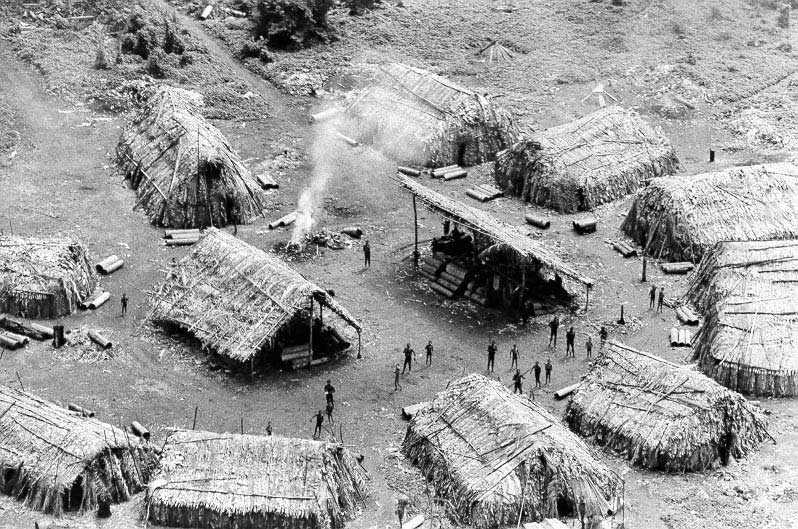

The Panará live in a large round village, with lodges positioned along the periphery of the circle. In the center is the Men’s Lodge, in the classic style of the villages of the Jê linguistic family. The village’s circle comprises the sites of the four existing clans and all lodges belong to these clans. The Panará cardinal points indicate the sites of the clans in the village circle, guided by the sun’s trajectory.

The names of the clans suggest spatial mapping of growth and maturation. The clans are called: kwakyati pe, kwasôti pe, kukre nô pe and kwôsi pe, all alluding to the processes of maturation. Kwa means "buriti palm tree"; kyati means "root" or "the place where the trunk plunges into the ground"; sôti means "leaf", "point" or "end"; kukre means "lodge"; and kwôsi means "rib." East, where the sun rises, is kwakyati pe; West, where the sun sets, is kwasôti pe. In other words, East is the root or the beginning, and West is the leaf or the end. The two polarized clans inscribe within the spatial organization of the village the sign of time, following the trajectory of the sun from sunrise to sunset. They map this spatial representation from the root’s growth process until the leaf’s development.

The clan names can refer to either the clan members or to the place, depending on pitch. For example: kwatyati pe means "the place of the buriti palm tree root"; or kwkyatanterà for "the people of the buriti root"; kwasôti pe for "the place of the buriti leaf", or kwasôtantera for "people of the buriti leaf". It is important to remember that the shape of the buriti palm tree is a straight trunk without branches, with leaves only at the top. In order words, it is the ideal tree to incorporate the root/leaves contrast. The buriti log is also used for log racing, a ceremony bearing enormous significance for the Jê groups in general and the Panará in particular.

The design of the village is a representation of the group’s total social universe. In the center of the village circle there were traditionally two Men’s Lodges where the adolescent boys lived. The Eastern one belonged to the kyatantera, "the people of the root, or the beginning," the Western one belonged to the sôtantera, "the people of the leaf, or the end." Those are the ceremonial halves, the societies of men, which split the village (East/West, Root/Leaf). The adolescent boys participate in log racing at key moments during the great ritual cycle.

The two other clans are not North/South. The kukrenô pe clan is located in the Southeast, and the kwasôti pe is in the Southwest, as though interposed amidst the two polar clans. The first, kukrenôwantera, means "the homeless people" and relates to the origin of the Panará society, at a time when social order did not exist, when their ancestors were homeless. They relate to a time prior to the world of Panará villages, agriculture, music or rites. The kwôsitantera, the "people of the rib", refers to death (when only bones remain) or a latter time, when social conviviality is gone. In the Panará social space architecture, time is included in full. It spans from before the world existed until after its existence, when it has already been. The village is the representation of totality, of space and time between "beginning" and "end."

Spatial relations rule the entire Panará kinship system. The clans have strong links with women, since everybody, without exception, belongs to the clan of their mothers. Names are given based on the house where the mother was born, where in the village circle the father was married and so forth.

Social relations

Male kinship plays an important role. Men convey Panará names. The father names the sons and the father’s sister, or some female kin to the father, names the daughters. Men give their own names to their sons, or the names of their brothers or other kin. Everybody has at least two names, and a few have a baker’s dozen. Everybody carries the name of some ancestor, and their mythical ancestors named the Panará, as well as the animals, the birds and the fishes.

Although there are mechanisms for the invention of names, as a rule, the system does not allow such a thing: a true name is the name of the ancestors, the suankyara, those "from before." The array of Panará names suggests nothing less than a list of all things in the world. Thus, Tekyã means "short shin"; Kokoti means "bloated"; Kyùti means "tapir"; Pè'su means "Brazilian nut"; Nansô means "rat"; Sampuyaka means "Matrinchã" (a type of fish, literally, "white tail"); Sôkriti, "fake leaf" or "something that resembles a leaf". Just as the clans permanently set the cardinal points of the Panará cosmology within the village circle, the naming system is a testament of their ancestors’ knowledge of everything that exists, setting into perpetual circulation the names from the mythical times of the early elders from generation to generation.

These are the basic relations that organize events in village life. Traditionally, boys live with their parents in the mother’s lodge until the age of 12 or 13. Upon reaching this age, they then sleep at the Men’s Lodge, as dictated by their ceremonial half. Following a few years of residence at the Men’s Lodge, the boys commence more serious relations with girls and gradually incorporate themselves into the lodges of their future wives. By residing at the Men’s Lodge, the relations between the boys and their families are severed. From this point in the cycle, they begin to create their own family by incorporating themselves into the lodges of their wives who will bear their children. Marriage is consolidated upon the birth of children.

Women do not simply belonging to the clans; they effectively are the masters of the lodges where they live with their husbands, their daughters and their daughters’ husbands and children until they, too, will commence their own family life. If a monogamist marriage ends – and it may end several times in adulthood – men leave the lodge. Marriages are commonly dissolved and people remarry four or five times over. The traumatic history of the group, rife with widowhood, prompted the need for flexibility.

Similar to other Jê groups, the Panará convey being a full adult by the words taputun, old man, and twatun, old woman. In order to be called these names, they must have married children and be a grandfather or grandmother. The sons-in-law must works for their in-laws tilling the fields for their wives and their wives’ families, hunting and fishing to feed their lodges and their mothers’ lodges and show respect, by way of a formal attitude of deference vis-à-vis the elders’ age group.

The youngsters (piàntui, young woman and piôntui, young man) handle the productive work: tilling the fields, hunting, fishing and food-production. The elders organize and oversee the work of the younger people by giving speeches delivered in the village yard or in the Men’s Lodge. In addition, the elders dictate the organization of the all-important rites of the Panará. Men play a major role in these activities since they have a highly favored place in ritual activities and ritual speeches. The men’s traditional role is with contact with those outside the Panará community, which traditionally happened by way of war. The influence of elder women, by turn, is effective in any decision that affects the village as a whole.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

Cerimonial life

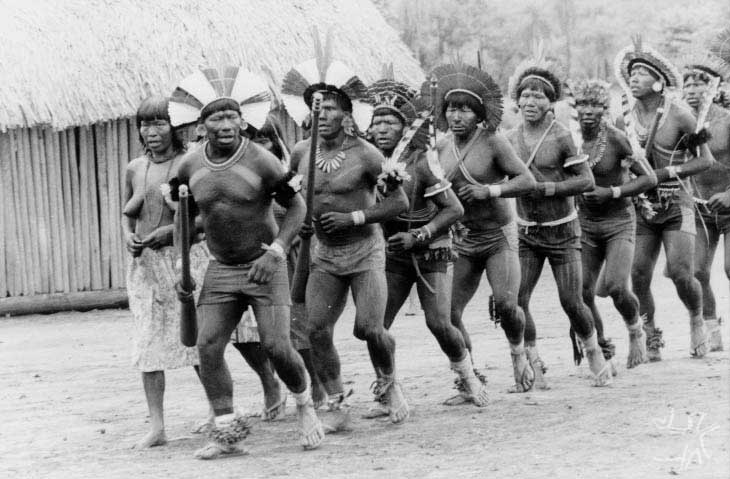

Log racing is the most important ceremonial activity for the Panará. It is the major public demonstration of male power and energy. Log racing is done at various times during the year, such as during the female puberty feast, or following warring expeditions, or by itself. Resuming log racing in the Xingu Park had a crucial significance in the social reconstruction process. For many years, the Panará did not build a Men’s Lodge in the Park, under the allegation that there were no boys. In fact, only after their last move inside the Park, when they installed their village in the Arraias river, did they build one. It was not merely by chance that at the same time they felt capable of building their Men’s Lodge, they also began the process of retaking their lands.

The issue of natural resources is crucial in understanding why living in the Xingu was a problem for the Panará. In their view, not only were they in a foreign land but also in a poor land. The reasons are numerous. In the Indigenous Park there is less game than in the Peixoto de Azevedo. Several key fruits that are important components of the gathering process for the Panará – including Brazilian nuts – do not exist there. In addition, the land is less fertile, the fields yield less, and deplete faster than their traditional land.

Given the Panará social and cosmological order, all this implies a loss beyond material desire. The forest, the rivers, the igarapés and the lakes are sources not only of material resources, but the basis of social order. The mythical ancestors, who named the Panará and the world, were "combined" beings – not just animals, but Panará people, too. The dead, who lived in the village of the dead beneath the ground, bred many animals that they in turn offered to the living to raise and slaughter. The living were to use these animals during sacrificial rites designed to keep relations among the clans on good. One interpretation of the scarcity of game in the Xingu is that "the dead give us no more." The relations between the living and the dead and between kinship and friends were in jeopardy because of this scarcity of game. For the Panará, the stars represent the Panará of the past - the small ones being men, and the larger, more brilliant ones, being women. A white man seeking a semblance of religion among the Panará would find nothing. Social life, natural world and cosmological life are integrated into the same order.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

Subsistence and way of life

Subsistence

First and foremost, the Panará are farmers, fishermen, and hunters. They grow maize, potatoes, yam, several banana species, cassava, squash and peanuts. In the fertile Peixoto and Iriri lands, the same banana trees yielded fruit for years on end, while the Xingu land requires new trees every year. The difficulty of working without steel tools was overcome by the purchase of knives, machetes and axes. Fascination with these tools prompted the Panará to attack the Englishman Richard Mason in 1961; to come to the Cachimbo Air Force Base in 1967, and to accept contact with Cláudio Villas Bôas in 1973. Knives and beads were the only booty taken from dead enemies in the wars against the Kayapó. As soon as they were given steel axes by the whites, they dumped their own stone axes into the river.

The Panará incorporate different techniques to ensure that they have a steady supply of food. Fishing is done both in the rainy and in the dry season, since the techniques to capture fish vary according to the water level: timbó (a toxic weed) is used in low-water season and bow and arrows are used during the flood. Hunting is the most prestigious male activity. Tapir, monkeys of several kinds, paca (a rodent), jacu, mutum and other hen-like fowl are shot down with bows and arrows or killed with the war club. It is the knowledge of the animals and the ecosystem, rather than force or technology, which ensures that the hunters return with the kill.

As gatherers, the Panará value the several species of honey they harvest, and they eat it pure, blended with açaí, or diluted in water. They also appreciate wild papaya, cupuaçu, wild cocoa, cashew, buriti, tucum, macaúba, inajá, mangaba, pequi and the all-important Brazilian nut, gathered between November and February, exactly in the period when the fields have already been planted but haven’t yet yielded.

For the Panará, social relations dictate the entire subsistence production process. The daily chores of each family core – women harvesting cassava or other produce, men going hunting or fishing – provide content to a transcendental ritual cycle. These complex service requests and provisions among clans mobilize the collective work force. This culminates in the collective preparation of a great quantity of cassava or maize, which in turn is a complement to a successful collective hunt that sometimes lasts weeks. At the conclusion of the ceremony, everybody prepares an immense paparuto (a cassava or corn pasta filled with meat, wrapped in banana leaves and baked in a ground oven). It is eaten every day, to be split among the clans and then to be consumed. The absence of game means, in the long run, that there is no way of maintaining the social architecture that the Panará live by.

In the same vein, the field is not only a highly socialized space but a space for fundamental material and social work as well. This helps explain the geometric shape of the fields. The circular design of the field, with certain plants along the periphery, and its lines, sometimes crossed, of banana trees or maize crisscrossing the center of the field, is a partial reproduction of the village space. The opposition between the center and the periphery, using the selfsame spatial concepts that dictate body painting and haircuts, is always in tune with the social system. The growth of maize and peanuts are time frameworks for piercing rites of ears and men’s lower lips and the etching of thighs, which, in turn, determine the exchange cycle among the clans. Having weak fields, which do not yield, is a problem, which shakes the entire social fabric of the Panará.

Way of life

The Panará remained hunters, fishermen, farmers and collectors during their time in the Xingu Indigenous Park. Jê nomads driven into sedentary life, the Panará have always made it clear that their society, as it was structured in the Xingu Park, was a makeshift version of what it was in their traditional land.

Unfortunately, the evidence of twenty years of Xingu life and the influence of the white man’s world is evident. Aluminum pans, salt, matches, kerosene and sometimes even sugar are found in their lodges. Changes in feeding habits and contact with microorganisms and bacteria have promoted tooth decay. Women wear dresses and men wear shorts. All have knives, axes and machetes, and a few have rifles or shotguns.

Adult women no longer wear the traditional cropped haircut, with two parallel lines running atop their heads. It has been replaced by long hair with fringes, in the Suyá female style. Body painting, feather artistry and music have also assimilated elements from the Xingu culture, mainly from the Kayapó, the Panará’s nearest neighbors.

The Panará’s rationale for organizing space, time, production, and the reproduction of life is evident through their ways of coexisting and talking to each other in the Panará language. Many speak Kayapó or Suyá or both. Nearly all understand some Portuguese. But only a few men speak this language with some fluency. Sophisticated speeches may resort to Portuguese words in their sentences, but important things are still said in the Panará language.

[Extracted from Panará: a volta dos índios gigantes, book by Ricardo Arnt, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Raimundo Pinto and Pedro Martinelli. São Paulo: ISA, 1998]

Sources of information

- ARAÚJO LEITÃO, Ana Valéria Nascimento (Org.). A defesa dos direitos indígenas no judiciário : ações propostas pelo Núcleo de Direitos Indígenas. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1995. 544 p.

- ARNT, Ricardo. Índios gigantes : uma história com um grande final feliz. Super Interessante, São Paulo : Abril, v. 10, n. 12, p. 36-45, dez. 1996.

- --------; PINTO, Lúcio Flávio; PINTO, Raimundo; MARTINELLI, Pedro. Panará : a volta dos índios gigantes. São Paulo : ISA, 1998. 166 p.

- ASSOCIACAO IPREN-RE DE DEFESA DO POVO MEBENGOKRE. Currículo do Curso de Formação de Professores Mbengokre, Panará e Tapayuna Gorona. s.l. : Associação Ipren-Re, 2001. 92 p.

- BARUZZI, Roberto Geraldo. et al. The Kren-Akorore : a recently contacted indigenous tribe. In: HUGH-JONES, Philip (ed.). Health and disease in tribal societies. Amsterdam : Ciba Foundation, 1977. p. 179-200. (Ciba Foundation Symposium, 49, Excerpta Medica).

- --------; RODRIGUES, Douglas et al. Saúde e doença em índios Panará (Kreen-Akarore) após vinte e cinco anos de contato com o nosso mundo, com ênfase na ocorrência de tuberculose (Brasil Central). Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 17, n. 2, p. 407-12, mar./abr. 2001.

- COHEN, Marleine. O caminho de volta : a saga dos gigantes Panará. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 601-9.

- COWELL, Adrian. The tribe that hides from man. London : Pimlico, 1995. 312 p.

- DOURADO, Luciana Gonçalves. The advancement of obliques in Panará. Santa Barbara Papers in Linguistics, Santa Barbara : UCSB, v. 10, , 2000.

- --------. Aspectos morfossintáticos da língua Panará (Jê). Campinas : Unicamp, 2001. 240 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Estudo preliminar da fonêmica Panará. Brasília : UnB, 1990. 61 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Fenômenos morfofonêmicos em panará : uma proposta de análise. Boletim do MPEG, Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, v. 9, n. 2, p. 199-208, 1995.

- EWART, Elizabeth J. Living with each other : selves and alters amongst the Panará of Central Brazil. Londres : Univ. of London, 2000. 364 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- GIRALDIN, Odair. Cayapó e Panará : luta e sobrevivência de um povo. Campinas : Unicamp, 1994. 208 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)Publicado pela Ed. da Unicamp na Série Pesquisas em 1997 com o mesmo título.

- GUEDES, Marymarcia. Siwiá Mekaperera-Suyá : a língua da gente - um estudo fonológico e gramatical. Campinas : Unicamp, 1993. (Tese de Doutorado)

- HEELAS, Richard Hosie. The social organisation of the Panara, a Ge tribe of Central Brazil. Oxford : Univ. of Oxford, 1979. 405 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- LEA, Vanessa R. Laudo histórico-antropológico relativo ao Processo 00.0003594-7 - Ação Originaria de Reivindicação Indenizatória na 3ª Vara da Justiça Federal do Mato Grosso. São Paulo : s.ed., 1994. 130 p. (AI: Parque Indígena do Xingu)

- LOFREDO, Sônia Maria; RODRIGUES, Douglas et al. Investigação e controle de epidemia de escabiose : uma experiência educativa em aldeia indígena. Saúde e Sociedade, São Paulo : Faculdade de Saúde Publica, v. 10, n. 1, p. 65-86, jan./jul. 2001.

- MÜLLER, Cristina; LIMA, Luiz Octávio; RABINOVICI, Moisés (Orgs.). O Xingu dos Villas Bôas. São Paulo : Agência Estado, 2002. 208 p.

- NUNES, Maria Angélica de Lima. Estudo da resposta humoral a antígenos de plasmódios em índios Panará. São Paulo : USP/ICB, 1999. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SCHMIDT, Marcus Vinicius Chamon (Coord.). O conhecimento dos recursos naturais pelos antigos Panará : levantamento de recursos naturais estratégicos da Terra Indígena Panará. São Paulo : ISA, 2002. 58 p.

- SCHWARTZMAN, Stephan. Laudo etno-histórico sobre "Os Panará do Peixoto de Azevedo e cabeceiras do Iriri : história, contato e transferência ao Parque do Xingu". s.l. : s.ed., 1992. 44 p.

- --------. Panará : a saga dos índios gigantes. Ciência Hoje, Rio de Janeiro : SBPC, v. 20, n. 119, p. 26-35, abr. 1996.

- --------. The Panara of the Xingu National Park : the transformation of a society. Chicago : Univ. of Chicago, 1987. 436 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- VERSWIJVER, Gustaff. Considerations of Menkrangoti Warfare. Rijks University, Gent: 1895.(Tese de doutorado)

- VILLAS BÔAS, Cláudio; VILLAS BÔAS, Orlando. A marcha para o oeste : a epopéia da expedição Roncador-Xingu. São Paulo : Globo, 1994. 615 p.

- VITÓRIA dos índios gigantes : concedida indenização aos índios Panará. Rev. do TRF-1a. Região, Brasília : TRF, v. 12, n. 2, p. 54-64, dez. 2000.

- WURKER, Estela; WERNECK, Adriana (Orgs.). Priara jo kowkjya. São Paulo : ISA, 2002. 82 p.

- O Brasil grande e os índios gigantes. Dir.: Aurélio Michiles. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 47 min., 1994. Prod.: Elaine César; Instituto Socioambiental.

VIDEOS