Kisêdjê

- Self-denomination

- Khisêtjê

- Where they are How many

- MT 536 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Jê

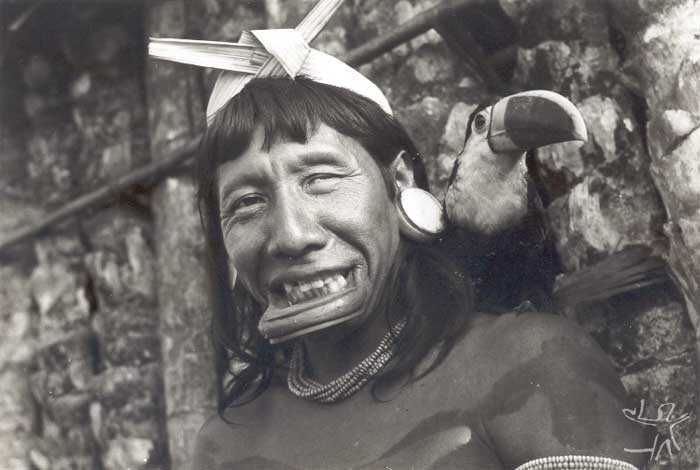

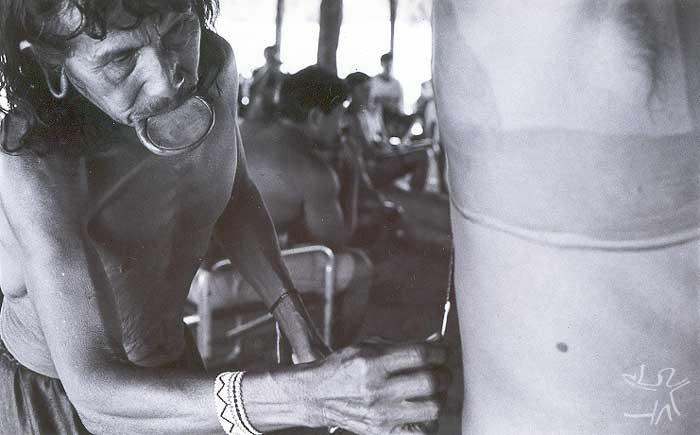

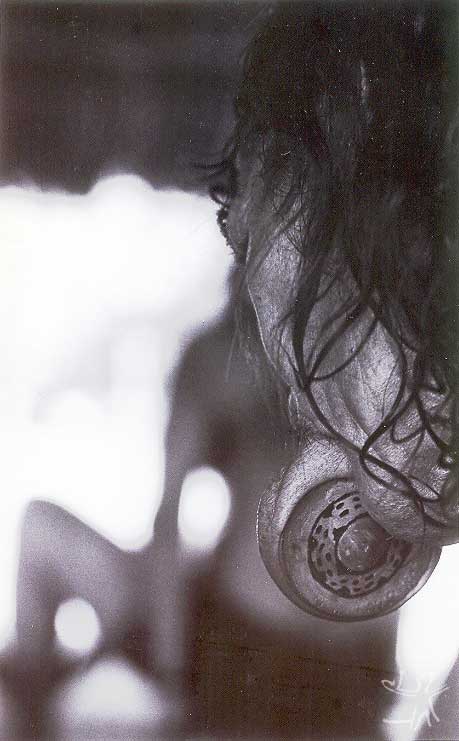

The Kĩsêdjê are the only group of the Gê language family in the Xingu Indigenous Park. But since their arrival in the region (probably in the second half of the 19th century), because of contact with other Xingu groups and, primarily, with those of the so-called "cultural area of the Upper Xingu," they have adopted many new customs and technologies. In spite of this, they never abandoned their cultural singularity. Among the principal features of this are a particular style of singing in rituals, an expression of individuality, and of a way of being in Kĩsêdjê society. Until a few decades ago, another distinguishing feature of the group was the large lip discs and ear discs that more than simply being ornaments pointed toward the importance of speaking, singing, and listening among members of this group.

Myth and History

The place to begin a discussion of the history and cultural dynamics of the Kĩsêdjê is in their mythology. Differently from some indigenous groups, such as those in the Upper Xingu, Kĩsêdjê society was not established by a creator or by a culture hero, but developed in a series of events involving "normal" human beings. Kĩsêdjê society took form through the appropriation of specific elements of animals and enemy Indians. Thus, fire and cooking were obtained from the jaguar; corn and the practice of planting were obtained from a rodent; and the naming system (basic for social identity and all ceremonies) was obtained from an enemy group that was said to live underground. The Kĩsêdjê said that much later they encountered a group somewhat similar to themselves that used lip discs and scarred their bodies but that were cannibals. They incorporated some of that group's non-dietary customs as well. Songs were learned from mythical enemies, from Kĩsêdjê in the process of metamorphosis into other animals, and from other indigenous groups. Thus the vision the Kĩsêdjê have themselves is of society formed through the selective appropriation of what was good and beautiful of other beings.

Kĩsêdjê oral history is rich and detailed, and what is given below is only a summary of a history they pass on through word of mouth from generation to generation. The closer to the present, the more detailed the commentaries. The Kĩsêdjê say that in a distant past they came from the Northeast and the region of the north of the Tocantins River or from the state of Maranhão. From there they moved in a westerly direction, crossing the Xingu River and reaching the Tapajos River. There they fought with a series of indigenous groups, among them those they identified as the Mundurukú and the Krenakarore (Panará). Always fighting, they moved in a southerly direction toward the headquarters of the river. The Kĩsêdjê then moved to the East to the headquarters of the Batovi River and entered into contact with the Upper Xingu societies. Another Kĩsêdjê group (that came to be called the Tapayuna) eventually moved in the direction of the Sangue and Arinos rivers, where they were subsequently (and disastrously) "pacified," in 1969.

The first contact of the Kĩsêdjê with a nonindigenous society probably occurred during the visit of the expedition led by the German scientist Karl Von den Steinen. He and his expedition camped on a sandbar across the Xingu River from the Kĩsêdjê village from September 3rd to 26th, 1884. The description of the scientist emphasizes the difference between the Kĩsêdjê and the other groups of the region. He described them as painted in black and red ("without art"), sleeping on the ground, in small houses, with a very simple material culture and a "men's house" that, unlike those of the Upper Xingu, had no walls. The Kĩsêdjê said that before permanent contact with Europeans, their ancestors called them "people with the big skins" because their clothing hung loosely on their bodies.

There is no exact date for the arrival of the Kĩsêdjê in the Xingu. From the commentary of some, one could estimate that it occurred in the first half of the 19th century. The relationships between the Kĩsêdjê and the groups that they encountered in the Upper Xingu varied between harmony and hostility. As a consequence of suspected witchcraft (which caused many deaths among the Kĩsêdjê) and attacks, they moved north to the mouth of the Suiá-missu River. There the Kĩsêdjê attacked the Manitsauá and also captured women and children from the Iarumá (neither group survives today). Thus both the Manitsauá-missu and the Suiá-missu affluents to the Xingu were freed for use by the Kĩsêdjê.

The Juruna (yudjá) and the Northern Kayapó entered this region in the end of the 19th century from the north, under pressure from the expansion of Brazilian frontier settlements. Both of these groups attacked the Kĩsêdjê. The Kĩsêdjê, as a consequence, moved some kilometers up the Suiá-missu River to a new village. It appears that Kĩsêdjê participation in Upper Xingu life diminished during this period. They fought with the Waura and captured some women from them. They recall this first village on the Suiá-missu River as the place where they adopted hammocks for sleeping (before this they slept on woven mats) and as the place where some captured Upper Xingu women taught Kĩsêdjê women an important women's ceremony from the Upper Xingu called Yamuricuma. This event gave the name to the village site, still called Yamuricuma.

After suffering further attacks from their enemies, the Kĩsêdjê moved further up the Suiá-missu to a place near the mouth of the Wawi River. There they constructed a large new village with a Gê spatial layout and two "men's houses." In this village they were attacked by a group of Juruna Indians and their rubber tapper allies armed with Winchester rifles. They killed many Kĩsêdjê and destroyed the village. This attack almost ended the Kĩsêdjê as a separate group. Some Kĩsêdjê went to live with relatives and allies in the Kamaiurá village in the Upper Xingu; others moved further still upstream on the Suiá-missu River to escape further attacks from the Juruna and Northern Kayapó. This period of dispersal is remembered as a time of intense contact with the Upper Xingu and of the "Xinguanization" of the Kĩsêdjê. After a time they resolved to unite again in a new village, but a group of Kĩsêdjê suffered another attack from the Northern Kayapó. This led to a lack of women in the village, and the Kĩsêdjê attacked the Waura to obtain more women (and women who could make pots). The Kĩsêdjê then retreated into a maze of small rivers where they remained almost completely isolated from any contact with other groups. The villages they lived in during this period were in the same region they have returned to in the beginning of the 21st century after recovering the right to that territory.

Life in the Xingu National Park

In 1959, the Villas Bôas Brothers sent a group of Juruna to make peaceful contact with the Kĩsêdjê. The Kĩsêdjê refer to this time as when "the whites came to look for us." The Juruna visit was followed shortly afterward by an expedition in motor boats, and the Villas Bôas and others visited one of the Kĩsêdjê villages. The Kĩsêdjê received at the Brazilians peacefully and sang for them. A little after this, the Kĩsêdjê moved closer to the Indian post, Diauarum, at the suggestion of the Villas Bôas, so that they could receive better medical care. They made a new village at Yamuricuma, on the Suiá-missu. There they were visited by anthropologists Harold Schultz (also a photographer), Amadeu Lanna, and the photographer Jesco von Putkammer.

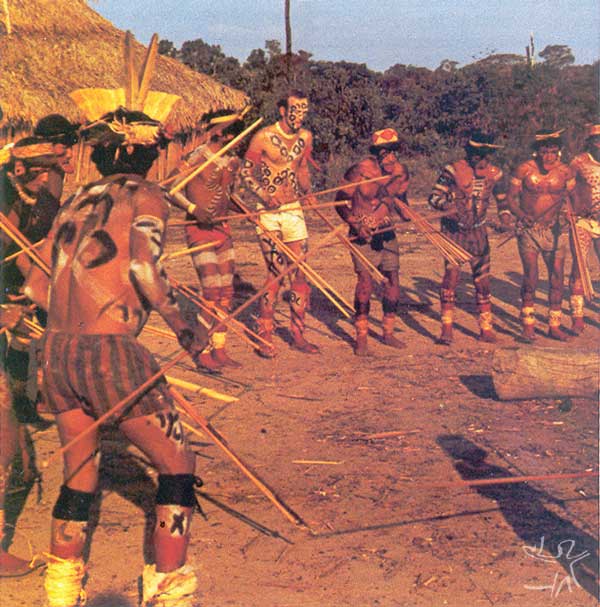

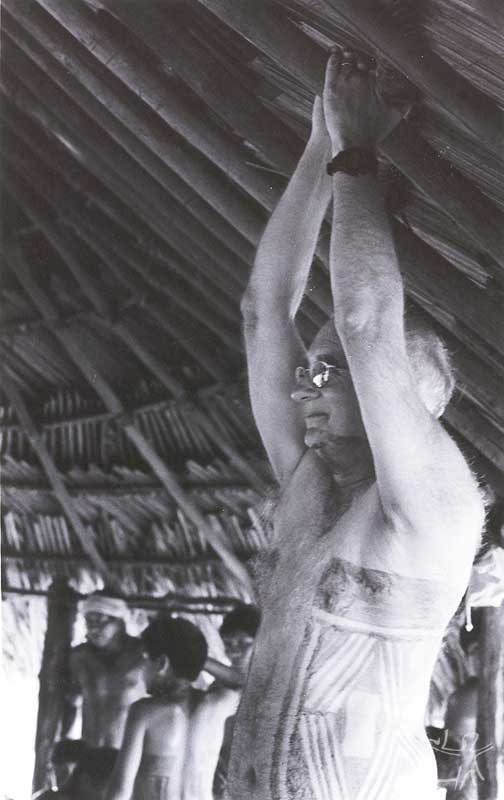

In Diauarum they met their former enemies: the Juruna, Trumai, and Metuktire (Kayapó), as well as the recently arrived Kaiabi. They constructed a village in the Xingu style and a number of Kĩsêdjê married Trumai. These new marriages were very different from the earlier incorporation of captives because in this case Trumai men came to live in the village with their Kĩsêdjê wives. Subsequently, some Kĩsêdjê women married Juruna and Kaiabi men. The Kĩsêdjê performed a number of ceremonious of these other communities (photographed by Jesco von Putkammer). In the 1960s, the young men began to cut their hair in the style of the Upper Xingu. The use of ear discs and lip discs was abandoned and children's ears began to be pierced in an Upper Xingu style. The death of all of the older men in the years following contact was another important factor in their Xinguanization, because there were no longer enough older men to continue performing the Gê rites of passage.

The close link between the Trumai and the Kĩsêdjê ended when a Kaiabi killed a Trumai married to two Kĩsêdjê women. As a result of the hostility, the Trumai moved south to Posto Leonardo Villas Bôas, and the Kĩsêdjê moved further up the Suiá-missu River to a new village. They continued to have close contact with the Juruna and Kaiabi, and adopted from them forms of weaving and some crops. They were once again asked to move closer to Diauarum to facilitate medical assistance and constructed a village near the mouth of the Suiá-missu that abandoned both Gê and Xinguano characteristics. The village was neither circular nor did it have a "men's house" in the center. The house walls were made of upright logs and resembled the constructions in Diauarum, which had a strong resemblance to Kaiabi villages.

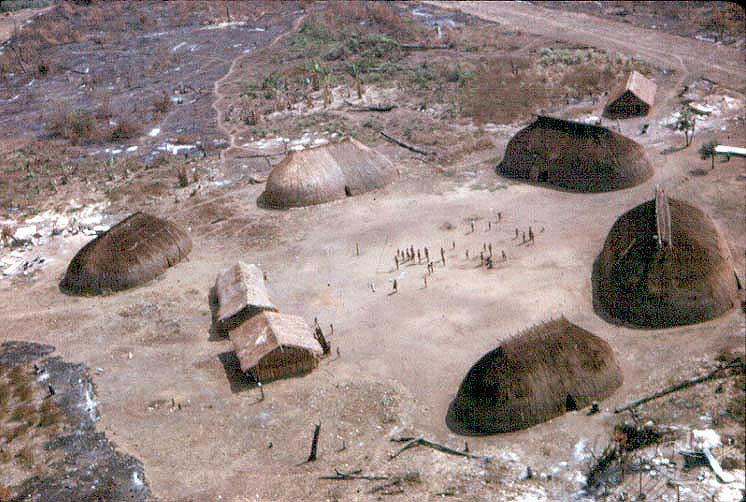

In 1969, as a result of the disastrous contact with the "white pacifiers" 41 Tapayuna survivors (or "Western Kĩsêdjê" also known as "Beiços de Pau" because of their large lip discs) were removed from their land between the Arinos and Sangue rivers to join the Kĩsêdjê (who at that time numbered approximately 65). Ten more members of the group died shortly after their transference as a result of diseases. From the perspective of the Eastern Kĩsêdjê, however, the cultural resemblances of the two groups considerably changed the emphasis within their own culture. The Tapayuna looked like, spoke, and acted like their Kĩsêdjê ancestors. The Kĩsêdjê called the Tapayuna "New Kĩsêdjê" and were fascinated by how they appeared to be living ancestors. As a consequence, the Kĩsêdjê felt themselves stronger, more numerous, and with a greater future. In the space of one year, a new village was built in a traditional Gê pattern, with a circle of houses surrounding a large cleared plaza, in which they constructed a men's house. During intensive discussions of their respective ceremonial and musical traditions, the two groups performed a number of Gê ceremonies together. They discovered that they had many traits in common.

The attitude of the Kĩsêdjê with respect to the recent arrivals was, however, ambiguous. At the same time as they were authentic Kĩsêdjê, they were also considered somewhat "backwards" because they did not know the customs and technology as of the Upper Xingu Indians. For example, they did not know how to process manioc in the Upper Xingu style, or how to make or paddle canoes. They spoke in a manner that the Kĩsêdjê considered somewhat strange and archaic even though it was clearly the same language. For this reason, they were treated with considerable humor and they were taught the new technologies.

In 1980, the Tapayuna felt themselves sufficiently strong to construct a village of their own, above the junction of the Suiá-missu with the Xingu River. Only a few orphans and adults that had married Kĩsêdjê remained in the Kĩsêdjê village. A Tapayuna leader was killed by the Kĩsêdjê and, fearful of further attacks, the few surviving Tapayuna moved to live with the Metuktire, where they remain until today (see Lea, 1997).

Leaving history and returning to mythology again, the adoption of selected culture traits from other peoples that punctuates the history of the Kĩsêdjê is based in their mythology (and the mythology of most of the other Gê peoples). Thus, as in myths, the Kĩsêdjê continue to adopt elements of indigenous and also nonindigenous societies when they appear to be "good" or useful.

In the case of the Upper Xingu, the Kĩsêdjê learned a good part of their technology without, however, abandoning their own. From early in their contact, they adopted Upper Xingu techniques of processing manioc (probably learned from a Tupi group such as the Kamaiura, since the words they use for many manioc species are derived from Tupi words). The Waura captives taught the Kĩsêdjê women how to make pots and griddles for beiju. They Kĩsêdjê also began to use other subsistence techniques: canoes for travel, linguistic elements, housing styles, ceremonies, body ornamentation, and a great part of Upper Xingu material culture. On the other hand, the Kĩsêdjê never ceased to hunt and eat animals that the Upper Xinguanos never ate, to plant corn and sweet potatoes for ceremonial use, and to produce Gê artifacts for ceremonies. Thus, the adoption of elements of Upper Xingu was extensive but they say that they selected the things that seemed beautiful and useful, ignoring the others.

Location and Territory

Presently, the Kĩsêdjê reside in several villages and posts. Ngôjwêrê, a village established at the edge of the Wawi Indigenous Territory (reconquered by the Kĩsêdjê as described below), is where the largest part of the population has lived since 2001. This is the location of an old village where one part of the group lived in the years before their contact with the Villas Bôas in 1957. Before the year 2000, the Kĩsêdjê inhabited the village Ricoh (Riko), currently abandoned. They go there to gather some crops from their old gardens, as well as to obtain piqui and mango fruits. Like their current village, Ricoh was built next to an earlier village of theirs, where they had been attacked by the Juruna and rubber tappers (see above).

Part of the Kĩsêdjê live in a village called Ngôsokô, where they moved when they began to agitate for the establishment of the Wawi Indigenous Territory in the 1990s, before the official establishment of this indigenous area. In addition, there are two small villages in each of which lives an extended family: Roptotxi and Beira Rio.

The Wawi Vigilance Post, located on the bank of the river with the same name, is run by the Kĩsêdjê, and two extended families live there. The indigenous Post Diauarum is also inhabited by some Kĩsêdjê families, especially those of people currently working for the nongovernmental organization Associação Terras Indígenas do Xingu (ATIX) or for the government organization Fundação Nacional do Índio (Funai). The families living at the Post also have houses in the villages. In addition, one Kĩsêdjê owns a house in Canarana, a city near the Xingu Indigenous Park which serves as a point of arrival and departure for trips to other Brazilian cities. Members of his family use the house when they go to the city.

The Kĩsêdjê have distinguished themselves in their fight for their lands, not only in actions taken to recover their traditional lands that were left outside the limit of the Xingu Indigenous Park but also with respect to environmental issues affecting their rivers and forests. To protect the Suiá-missu River and their traditional territory they have captured a number of fishing expeditions and other invaders of their territory.

When they saw that the waters of the Suiá-missu were becoming brown with sediment and covered with oil slicks they made an expedition in September 1992 to find out why it was happening. Five Kĩsêdjê and the chief of the Indigenous Post Diauarum traveled up the river to the Jaú Ranch-- also known as the Roncador Ranch--which is one of the largest agribusinesses in the region. They encountered an enormous dredge engaged in deepening and straightening the bed of the Daro River, a tributary of the Suiá-missu, creating huge muddy outflows into the river. Two years later, the pollution had reached the Xingu River itself. At that time the Kĩsêdjê made a new expedition to the ranch, this time accompanied by members of other indigenous groups from the Park such as the Ikpeng and the Kaiabi, as well as the head of Diauarum. A total of 10 men ascended the river. The dredge was still there and the owner of the ranch argued that the deepening of the river was behind schedule and would last a few months longer. This case awakened the perception of a very worrisome future for the Kĩsêdjê. With the occupation of the watershed of the Suiá-missu River by ranches, the Indians had lost control over one of the most important of their resources, including those stemming from the Suiá-missu and its most important affluents. They realized that all of the pollution from the headwaters drained into the Park polluting all of the rivers in its interior areas.

Another important act of the Kĩsêdjê was stopping the deforestation being undertaken by ranches on the Wawi River. The Wawi is the first river that enters the Suiá-missu; it is also known as the Santo Antônio River. In 1994, the Kĩsêdjê took control of the river and the ranches, in spite of the protest of the ranchers affected, and insisted that the entire area be recognized as indigenous land. Although they knew that it would be impossible to recover control over the whole Suiá-missu basin, since it extended far beyond the boundaries of the Xingu Indigenous Park, the Kĩsêdjê wanted to control the smaller drainage basin of the Wawi, whose headwaters are within the Park, but the rest of which flowed through lands ceded to ranchers. The Kĩsêdjê were victorious in this reconquest, and the Wawi Indigenous Land was formalized in 1998.

In spite of this success, the deforestation undertaken by the ranchers outside their area has not ceased and has greatly concerned the Kĩsêdjê communities. They have recently sent messages to both their neighbors and to authorities denouncing the widespread planting of soybeans on lands adjacent to their territory. They threatened that "if a soy planting machine comes here we will break it into small pieces." The multinational agribusiness Cargill, which processes soybeans, is establishing new units for storage and processing in Mato Grosso. One of them is in Canarana, and another is almost completed in Querência, the city nearest Kĩsêdjê territory. In addition, the multinational has announced that it will construct another unit on the land of the Gabriela Ranch, 40 kilometers south of the Xingu Indigenous Park. Anyone who travels the road that links Canarana to the Kĩsêdjê village cannot help but notice the rapid expansion of soy plantations and the increased deforestation associated with them. The intensive plantation of soybeans implies not only deforestation, but also the use of insecticides and chemical fertilizers that will further pollute the river the Kĩsêdjê use to obtain their livelihood. The final results of this conflict will not be decided for some time, but the Kĩsêdjê continue to be active participants in protecting their territories and the environmental health of their waters and lands.

Music and Cosmology

The Kĩsêdjê emphasize hearing and speech as particularly social faculties. Vision and smell are associated with animals and dangerous beings. The two faculties the Kĩsêdjê consider social were traditionally emphasized with body ornaments-- through large ear discs and lip discs. The eyes and nose were not ornamented (for further observations on this topic see "ornaments"). Even though they no longer use ear discs and lip discs today, due to the strong influence of Upper Xingu and Brazilian societies, the ears and the mouth are conceptually privileged organs for expression and a synthesis of the Kĩsêdjê concept of person

The Kĩsêdjê word associated with hearing, kumbá, has a much broader significance than the Portuguese word "ouvir." It signifies hear, understand, and know. These attributes are highly valued. The Kĩsêdjê say that the ear is the receiver and the location for storing social codes and knowledge rather than the "mind" or "brain" as described in English. When the Kĩsêdjê learn something, even when it is.

In many nonindigenous societies, discourse is emphasized over music. Everyone can speak, but only a few will sing in public. Among the Kĩsêdjê the opposite occurs-- everyone sings, but not everyone is expected to speak in public. Singing is the height of oral expression both individually and collectively. Among the Kĩsêdjê, as in other societies of lowland South America, indigenous people only needed to work three or four hours in a day to obtain the basic subsistence, and sang for almost as many hours. During ceremonies they might sing for as many as 15 hours without stopping.

Speech is privileged among the Kĩsêdjê as well, who employ various categories of discourse. The Kĩsêdjê language is divided in a general way into "everyday language" (kaperni) and “plaza speech" (ngaihogo kaperni). There are several kinds of plaza speech, including angry speech (grutnen kaperni), and speech that everyone listens to (me bai hwa kaperni). While everyday language is used in daily discourse by men and women of all ages, the various types of oratory are only spoken by fully adult men. They have specific rhythms, established language formulae, appropriate performance spaces, and particular performance styles. Even though women do not speak in the plaza, they also have certain more elaborate forms of speech and were also in the past specialists in ritualized crying, or laments. The melodies of the laments resemble the melodies of the men’s shout songs (akia).

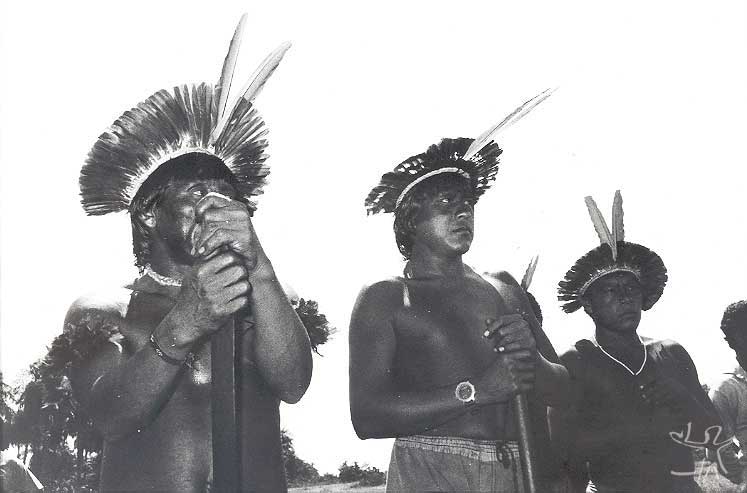

The Kĩsêdjê use and identify several genres of song, among which are two contrasting genres of song: akia, sung only by men, and ngere, sung by both men and women. The shout songs are a means through which Kĩsêdjê men speak publicly about their individual identity. They are songs composed and sung by males in a high voice with characteristic melodic structures and styles. The Kĩsêdjê say that only they sing shout songs, which differentiates them from other Indian groups.

Shout songs are part of plaza rituals, but also may be sung outside the village periphery. For many ceremonies, a man should have a new shout song which he sings in a way to be heard individually. Each person sings a different song, but all of them sing at the same time, and to the same tempo established by their rattles. Thus. a group of men will sing different songs at the same tempo and in a unison rhythm marked by their feet and rattles. The effect is a kind of strident cacophony, which is in fact a polyphony of strained voices singing as high as they are able in order to be heard by their sisters and lovers above the voices of the others. In the ceremonies in which men sing shout songs, women are principally members of the audience and providers of cooked food.

The women, on their side, have their own ceremonies in which they play the principal roles and are listened to by the men. As with men, certain women are recognized as masters of certain ceremonies. Over the years men have been incorporating songs from other indigenous groups, such as the "people living under the ground," the Munduruku, and the Upper Xingu global replace U societies. In the same fashion, Kĩsêdjê women have introduced new songs into the Yamuricuma ceremony, originally learned from Upper Xingu women.

When Kĩsêdjê listen to one another sing shout songs, they think not only about the general situation of the group, but also about how particular men are feeling with respect to something. Kĩsêdjê shout songs are one of the ways men express something about themselves and their attitudes. When a man is angry or sad, he will not sing at all or will sing very quietly. When he is happy, his voice will sound out of above all the rest. The unison songs are different, since they are sung by a group in a low voice. They are sung almost exclusively inside the men’s house, in the patio, or inside the residential houses on the periphery of the village. They are rarely sung outside the village.

A unison song is sung by a ceremonial group whose constitution is not necessarily based on kinship, marriage, or subsistence activities, but on names a child received after birth. In unison songs, each man combines his voice with those of the others so as not to be distinguished individually. On the other hand, each ceremonial group may sing different songs or in different styles from other groups. Thus the two ceremonial moieties may sing at the same time, but one of them will sing more slowly while the other sings more rapidly, and they will sing about different animals. The care with which the unison songs are performed in a single voice contrasts with that of the shout songs, and is a musical expression of the identity of a ceremonial group.

With the exception of certain flutes (which are rarely played) that the Kĩsêdjê adopted from Indians of the Upper Xingu, Kĩsêdjê music has always been predominantly vocal. The only instruments traditionally played are various types of rattles, which may be held in the hands, tied on the knees, worn as a belt, or affixed to other parts of the body. Kĩsêdjê euphoria is produced by singing and by food rather than through the use of alcohol, hallucinogens, or narcotics found among other indigenous groups in the Amazon basin. Singing and dancing for long periods of time is a physiological experience that also probably alters perception and creates euphoria.

In their cosmological universe, the Kĩsêdjê sing because by singing they can restore certain types of order in their world, and also create new types of order in it. As a physiological and social experience song is an essential mode for articulating experiences of individual lives with larger social processes. In a society where everyone makes music, “music making" is also dancing, political activity, and communicating something essential about oneself.

Rituals and Society

Many features of Kĩsêdjê social organization and ritual life were modified after the attack on their village by the Juruna and their rubber tapper allies. Population loss, intense contact with the Indians of the Upper Xingu, and the death of a large number of the older men shortly after “pacification" resulted in profound modifications in Kĩsêdjê social life. In spite of this, it is important to describe their social organization and cosmology before these events since many aspects of the Kĩsêdjê way of life continue to the present.

The Kĩsêdjê live in circular villages, in houses constructed around a large open plaza where one or two "men’s houses" are located, one in the east and the other in the west. In the past, residence was predominantly uxorilocal. When a man married he went to live in the home of his wife's family. After his initiation, a man was expected not to return to live with his family or to eat with his sister because only couples, lovers, or same-sex groups ate together. A man never put his arm around his sister since the very gesture was indicative of the beginning of a sexual relationship. But a man could sing to his sister without going near her house.

According to the Kĩsêdjê, every socialized being has three components. These are the physical body -- which is the result of the father's semen accumulated and developed within the mother's womb-- a social identity transmitted through a group of names given by a mother's brother of a boy (or the father’s sister of a girl), and what might be called the "spirit," (shadow, reflection) unique to each physical objects and essential to human beings, since without it a person sickens and dies.

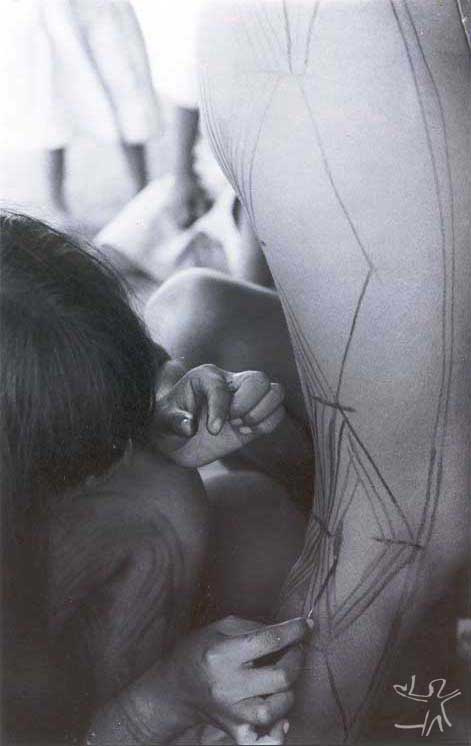

The Kĩsêdjê are very tolerant with their children, and do not expect them to hear-understand-behave well while they are young. They never strike their children but may tap them lightly on the head, to which children respond with copious tears. When children fight together the mother of each will blame her own child. When puberty begins, however, youths of both sexes are expected to listen to the instruction and exhortation of their parents and chiefs, and to act correctly in accordance with what they hear. At puberty Kĩsêdjê youths are considered "without shame" (añibakidi) if they do not observe the appropriate norms related to sexual activity, the distribution of food and property, and restrictions on eating and physical activities.

For a man, age grades are marked by elaborate initiation ceremonies that stress the breaking of ties with the natal household in the transferal of the young man first to the men's house (as sikwenduyi) and later to his wife's house as a "man with child" (hen kra) where he lives with her and her extended family after fathering a child.

There are fewer age grades and less elaborate initiation rituals for women, who continue to live in their mother's house throughout their lives. At puberty, some women remain for a period of time in seclusion within their houses, a custom adopted from the Upper Xingu. After puberty, a woman continues to live in her maternal household with her mother and sisters. She begins to take lovers and eventually becomes pregnant with a child. When her first child is born. a woman is given an area of her own within the house and her husband comes to live with her. They become a domestic unit separated conceptually from the other units in the large house, which usually has no internal physical walls. The larger residential house is composed of the parents of the woman, her single sisters and her married sisters with their husbands and children, as well as by her unmarried brothers. In addition to these, a house normally also includes orphans and/or captive children, visitors from other groups, and occasionally a visiting non-Indian.

A woman's status is related to her age and the number of children she has. Like a man, she begins with relatively little domestic authority, but this increases as her mother ages and she has more children of her own. With the beginning of menopause a woman’s status changes again, and she gains status in some aspects and loses in some others. Older women continue to participate in economic activities. They are intimately involved in the domestic lives of their children and can still undertake many of the women's tasks, although at a slower rhythm. Older women are also respected for their knowledge and are frequently consulted by younger generations, and are usually taken care of by their daughters and their families.

After they have a child, both men and women are referred to as "having a child" (hen kra). When they have many children both men and women are called "old" or "mature" (hen tumu or hen kwi ngIt). When their children marry and they have several grandchildren men and women enter another age grade and become "old clowns" (wikenyi). When a couple’s children marry they have sons- and daughters-in-law and a new status as central members of the residential houses. The difference between the members of the age grades hen kra and hen tumu is a question of degree, since older men participate more actively in political life. No rite of passage marks the change from "with child" to "mature." Some men begin to act like older adults earlier than others, depending on their personality and their position within various kinship networks. There is, however, a clear difference between the mature adult men and being an "old clown" (wikenyi), marked by a rite of passage and by changes in behavior during ceremonies.

Many Kĩsêdjê rites of passage can be seen as a ritualization of the transfer of a man from his natal residence to the house of his in-laws. When he has his own son-in-law, a man ceases to be an outsider. Male wikenyi complete this passage by becoming fully associated with the residence of their wives. Their complete integration is revealed by the differences between the initiation ceremonies of the "old clowns" from the other initiation ceremonies. Wikenyi change their body ornaments, their style of singing shout songs, no longer go hunting during certain festivals, and begin to receive special food from the rest of the village during ceremonies.

While initiated young men are considered the maximum expression of the ideal of masculinity and self-control, the behavior of the elderly is the opposite, characterized by humor, feigned lack of control, and obscenity. Just as the Kĩsêdjê do not expect children to act in a moral fashion, elders in Kĩsêdjê Society also have distinctive roles outside the norms that apply to younger adults. Certain of them act as clowns in rituals and wikenyi men give a characteristic falsetto cry while the rest of the men are singing. Wikenyi may also perform humorous pantomimes at the end of the afternoon, when the whole village may watch and enjoy their humorous activities.

Men and women who have married children and several grandchildren are candidates for the rite of passage that effects their transformation into old clowns. Women only become "wikenyi" after menopause. In the past almost all Kĩsêdjê became wikenyi, but pre-contact massacres and post-contact epidemics drastically reduced the number of people with the necessary age for this status. At the beginning of the 21st century, however, the characteristic cries of the elderly are once again being heard in ceremonies.

A majority of ceremonies emphasize the relations between a man and his real and classificatory sisters, as well as with his mother, over those he might have with his wife and in-laws . During non-ritual periods men bring fish and game to their wives and affines, and receive cooked food from them. During rituals men give food to their sisters and receive cooked food from them. They give their names to their sisters' sons and their daughters receive their names from a man's sisters. Brothers and sisters are therefore very important relatives for ceremonial purposes. Men sing for their sisters, but they do not sing love songs (there are none) but rather shout songs, songs of individual self-affirmation for their sisters who are socially and spatially distant because of uxorilocal residence and other changes due to family life.

When a Kĩsêdjê man paints his body for a ceremony of Kĩsêdjê origin (rather than Upper Xingu origin), the design he paints on his body is determined by the names he received from one of his mother's brothers at birth. Ultimately, all the members of a group of people with the same set of names paint and otherwise ornament themselves in the same fashion. Moiety membership is determined by names, as are a person's place in the line of dancers and the songs that he will sing with certain others. When they paint themselves for Upper Xingu ceremonies, Kĩsêdjê body paint designs are more individualized.

With respect to political power, the more influential men in a village are usually either leaders of political factions or specialists in ceremonial knowledge. A few others are influential because of how aggressive they are. The Kĩsêdjê say that the two essential features of a political leader are to coordinate the activities of the group and to resolve disputes through oratory. When a leader has finished his public speaking in a loud tone of voice in the central plaza, the whole village is expected to have "heard everything" (bai wha) and to behave accordingly. The authority of ritual leaders comes from their knowledge and their memory for songs. Leadership is generally inherited patrilineally, so that the children of a male leader are themselves potential leaders. Certain men who are "owners" of ceremonies learned from the Upper Xingu also inherit this right patrilineally. The daughters of a political leader also have considerable status, are active in public life, and their opinions are respected by the other women.

Body Ornaments

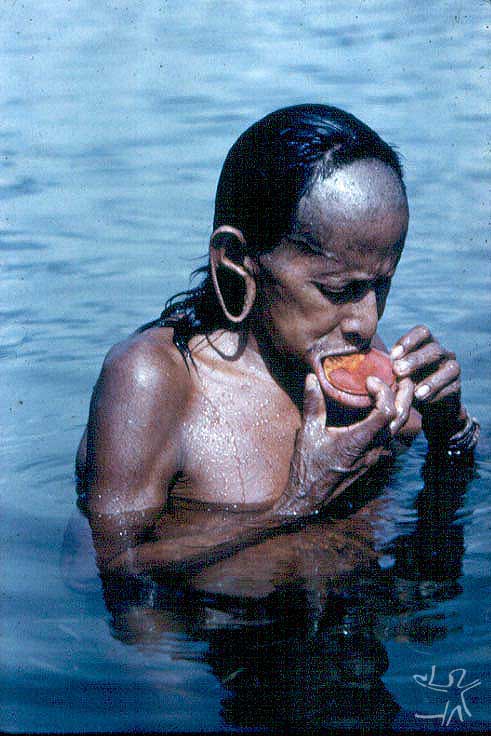

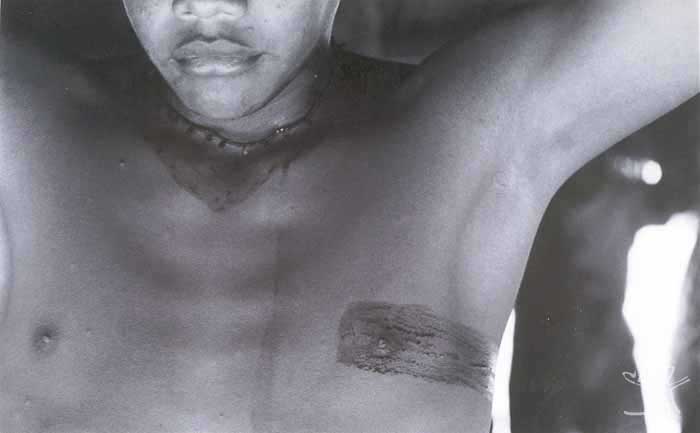

Body ornaments are inserted during rites of passage and are a mark of status. Kĩsêdjê body ornamentation has changed considerably since 1959. Before that, adult men and women carried large discs of wood or palm leaf spirals painted with white clay inserted in their ears. These discs could reach eight or more centimeters in diameter. Early in the 20th-century women stopped using these ornaments because of contact with groups in the Upper Xingu who do not use this form of ornament, but the men continue to stretch their ear lobes and wear them.

Men wore a lip disc in their lower lip. The lower lip was pierced and gradually stretched creating a narrow band of muscle which held an elliptical disc of light wood that could reach seven or eight centimeters. The lip discs were painted with red urucum on the top and sides but left the natural white color of the wood on the underside, with the exception of a small circular design representing the Pleiades constellation. This was painted near the center in a black dye made from genipapo surrounding a small raised area in the center of the underside of the disc.

Men frequently did not wear their ear discs during the day but they always wore their lip discs, only removing them to wash their mouths when they bathed. During ceremonies men would make and wear new ornaments in both their lips and their ears, which were often decorated with cotton strings and other ornaments.

Both sexes had their ears pierced at the earliest signs of sexual activity, if it had not already been done at birth. Men's lower lips were pierced between the ages of 15 and 20, when they reached the age at which they were considered fully adult and ready to enter the men's house. While they lived in the men's house, that is, before becoming parents and moving into their wives houses, young men were expected to make and wear steadily larger lip discs, and to sing a great deal.

Due to the decades of contact with other peoples within the Xingu Indigenous Park and with non-Indians, the Kĩsêdjê have ceased to use these body ornaments. In spite of this, the cosmological significance that the ornaments expressed still applies. Ear discs and lip discs were clearly associated with the cultural importance given to hearing as well as to speech and song. The Kĩsêdjê associated ear discs with hearing and lip discs with the speaking and singing. The ear was pierced so that a person would hear-understand-know well--not just physically but morally. They also said that the lip disc was associated with aggressiveness and bellicosity, correlated with masculine self-affirmation, speech, and song.

The color of the ornaments was also significant. Red is associated with heat and bellicosity. The circular design on the underside represents the constellation of stars that we call the Pleiades. The Kĩsêdjê say that the constellation is a group of young men in the sky. The ear discs were often painted white, a color associated with coolness and passivity.

When the nose and eyes are painted, as in hunting expeditions and in certain ceremonies in which men metamorphose into animals, they are usually painted black, a color associated with antisocial attributes and witches.

Smell, Vision, and Witchcraft

Unlike the faculties of speech and hearing, which are highly elaborated and positively valued in Kĩsêdjê society, the eyes do not have a similar degree of ornamentation or vision a positive evaluation. The Kĩsêdjê verb "to see" has a more restricted sense than is commonly applied in English. The eyes are not considered to be the "window of the soul," but rather a faculty that can be dangerous and antisocial. The symbolic emphasis on vision among the Kĩsêdjê is in the importance of the extraordinary vision possessed only by "witches" (wayangá). (The word "witch" is an unsatisfactory translation of this word; because they are antisocial people who can make people ill or kill them, it is the best rough approximation in English, but the terms are not identical).

A person becomes a witch when an invisible “witch-thing" enters his or her eyes. Certain species of birds also have a witch-thing in their eyes. People with the "witch-thing" in their eyes have extraordinary acuity of vision (resembling that possessed by the comic-strip hero Superman), allowing them to see the village of the dead in the sky and to look through the earth and see the fires of the people who live underground. They can also look around and see enemy Indians in distant villages, as well as what is going on in all of the houses in the village. They can turn themselves into birds, and fly into houses as well as travel long distances.

Since being a witch is neither congenital nor inherited, the "witch-thing" only enters the eyes of a person who is in some form or another immoral or "without shame" (animbai kidi). Witches are antisocial, selfish, and vindictive people who kill other people when they are angry. Men or women may be considered witches because they do not share their food or their belongings or because they do not observe appropriate sexual and elementary restrictions during critical periods. Other ways to become a witch include stepping on a new grave, having sexual relations with a witch, or touching a dead witch. People who do not listen to the exhortations of their elders, their political leaders, or the ritual specialists, are said by others to be without shame and thus run the risk of becoming thought to be witches by the rest of the community.

Kĩsêdjê witches see things that normal people are incapable of seeing. They do not hear-understand-know like normal people (in the sense of following the instructions of their elders). They have their own way of speaking, called "bad speech" (kaperni kasaga; kasaga means bad, or ugly). Witch's speech is something like malicious gossip, and can be distinguished from a political leader's plaza speech in several ways. It is only spoken in the interior of the houses and outside the village, never in the plaza; it is private rather than public; it is selfish rather than community-oriented.

The Kĩsêdjê say that witches are responsible for almost all deaths and sickness, which they cause by stealing the soul or spirit. When someone dies, the survivors attempt to discover the identity of the witch responsible. In the past someone would kill the one thought to be responsible for the death of important people. Not all witches caused death; soul theft could cause illness as well. People who became ill because of a witch but recovered could become "people without spirits" who were able to introduce new songs into the repertory of the village. They could do this because their souls had been carried by the witch and hidden in the village of some species of animal, plant, or fish. Those who were sick discover that they could understand the language of the species with which their spirit has been hidden, and from that time on they get better and sing songs learned from the species with which the spirit continues to live.

The sense of smell is thought to be most developed in animals and certain enemies who were said to track the Kĩsêdjê using their noses. The nose is not ornamented, and is rarely emphasized with body paint except to paint it black. Odors, however, are important parts of Kĩsêdjê cosmology. Odors are used to classify animals and human beings. Animals are divided into three groups by their odor; "strong," "pungent," or "bland" smelling animals each have specific attributes. Animals and other things classified as having a "strong smell" tend to be powerful and to a certain extent dangerous, like carnivorous animals, sexual fluids, and women. Things that are classified as having a "pungent" smell tend to be symbolically less dangerous. Pungent smelling animals are usually edible; almost all medicinal plants are said to be pungent smelling, as are many other things without great symbolic importance. The "bland" category includes animals and things that are safe to eat for most people most of the time, and fully initiated men

Economic Activities

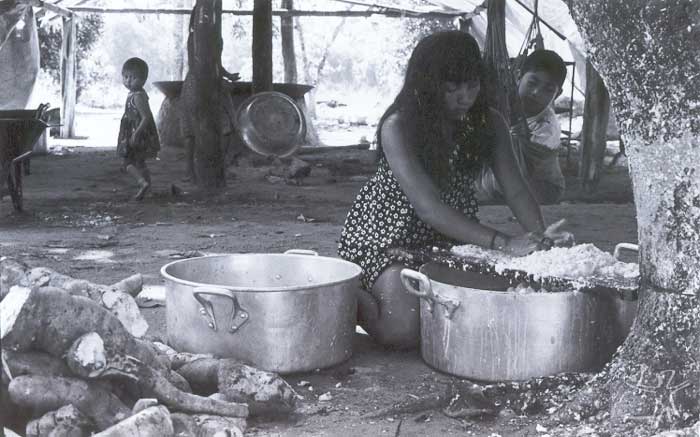

Women's economic activities tend to be undertaken by groups of female relatives living in the same house. They are usually oriented toward the extended or nuclear family. The work area for women is located inside or behind their residence. A great deal of women's time is taken up with the preparation of food from the products they bring from their gardens, especially the time-consuming processing of manioc, as well as cooking fish and game provided by their husbands. Before the 1980s, most cooking was done inside the residential houses. After that many houses built small shelters out back for cooking, away from the sleeping area, at least partly in response to a concern of visiting doctors about the effect of smoke and manioc fumes in the residences. By 2003, gas stoves were used in some houses. Several women usually work together processing manioc. Work is usually accompanied by lively conversation, and the women are usually surrounded by groups of children and pets as they work. Women also produce caxiri, a fermented drink made from manioc or corn learned from the Yudja (Juruna). Caixiri is made by all of the women living in a particular residence and is destined for the men of the group-- the women also partake of it.

Men's economic activities tend to take place outside the village. Men are responsible for cutting the trees to clear land for gardens, and they assist with the planting. Hunting and fishing as well as the construction of canoes and houses are often done by groups of men and boys who share a common residence. Manioc is the staple starch. Fish and game are considered to be noble foods--starch unaccompanied by fish or game is not a complete meal. Unlike the Indians in the Upper Xingu, the Kĩsêdjê consume a great variety of animals, including caymans. They do not eat jaguars and a other carnivores. Gathering activities contribute to the diet in a much more limited fashion than garden products, but are very important in certain seasons. The most important fruits are the piqui, the mango, and the fruit of various species of palm, especially the inajá. Like other groups in the region, the Kĩsêdjê eat very different things in different times of year. For example, piqui fruit has a quite limited season, but becomes ripe in a time when other foods are scarce. The Kĩsêdjê have a very sophisticated understanding of the environment in which they live and the availability of different foods in different ecosystems at different times.

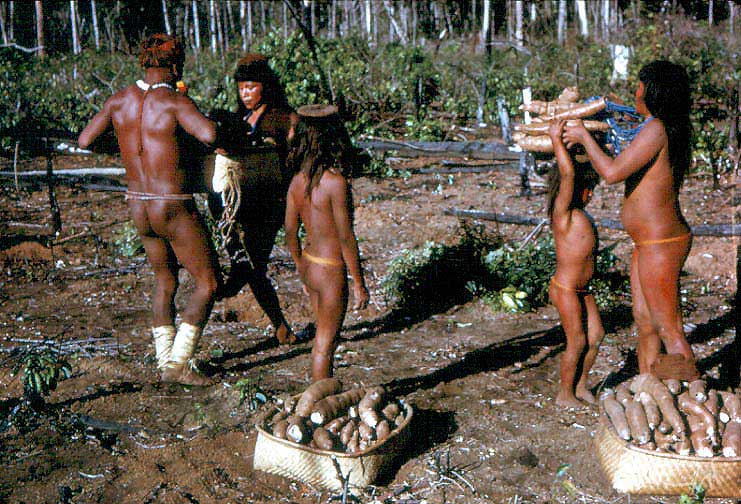

In the sexual division of labor in the garden, men prepare the earth for planting, cut down the trees and clear the brush for future gardens, burn the garden plots, and plant much of the manioc, bananas, and some other crops. Women generally harvest the gardens, transporting the crops in heavy bundles to the village where they labor long hours to transform the manioc into flour from which they make beiju, a thick starchy pancake. Women do plant some products, such as cotton. The planting, collecting, spinning, and weaving of cotton are exclusively women's tasks. Women also plant and collect corn, potatoes, various kind of beans, tubers, and some other crops.

Hunting and fishing activities are almost exclusively undertaken by the men, with the exception of timbó fishing during the dry season in which the entire community usually participates. Entire families also engage in looking for turtle eggs, but women never use a bow and arrow or gun.

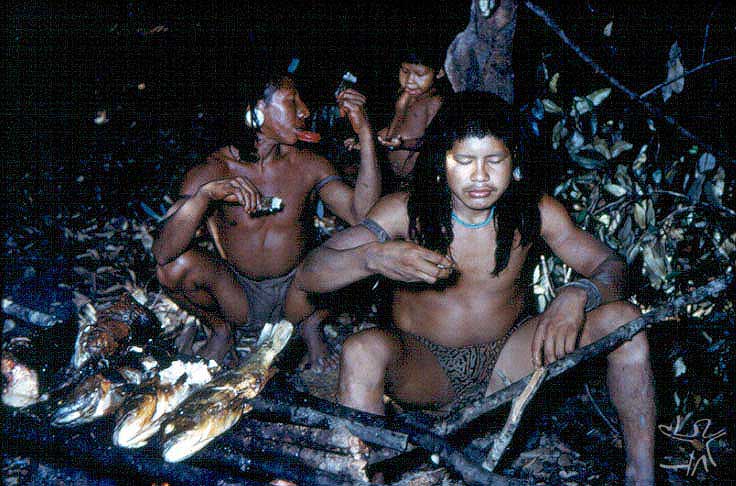

In the evening the members of nuclear families gather together near their houses or around a fire where they consume a meal and talk. Frequently one of the members of these groups crosses the patio to deliver food to other families. The foods that circulate among the houses are usually those brought by the men, especially fish, which are caught in large numbers during the dry season, as well as other perishable edibles collected in large quantities, including wild fruits and turtle eggs. Fish and game, however, are the principal food elements for inter-house distribution. When these exceed the minimum necessary for the nuclear family, they are distributed to the rest of the residential house, and to relatives in other houses. An entirely different form of food distribution occurs during ceremonies, when a group of men go hunting or fishing and the game is distributed to all the families in the village by one of the hereditary leaders. Such distributions are especially common during times of rituals, when collective activities of all kinds are frequent. Food distribution is carefully supervised by political leaders so that all families receive something.

Since 1998, the Kĩsêdjê have added a new subsistence resource to their already varied diet: beef from a cattle ranch that was already established in the Wawi area before their reconquest of it in the mid-1990s. They are learning the basic activities of cattle ranching and intend to substitute the infertile pastures with forest or to plant native fruit trees. These plans, however, require expensive machinery and training that is very difficult to obtain. The Kĩsêdjê are trying to find sources of funding for these important projects that will determine their future economic activities.

Indigenous Schools

Many years ago the Kĩsêdjê recognized the need to learn to read and write and to understand mathematics in order to interact with members of Brazilian society. In Ngôjwêrê, two trained Kĩsêdjê teachers are responsible for all the schooling. They use an alphabet script developed for the Kĩsêdjê language, and teach Portuguese as a second language. They follow the curriculum of the Political Pedagogical Project (Projeto Politico Pedagógico) developed by the indigenous teachers in the Xingu Indigenous Park, with the advice of a team from the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). This curriculum teaches history, geography, and mathematics; it has as its central themes the environment, health, pride in culture, and defense of territory.

The villages of Ngôsogô and Roptôtxi also have indigenous teachers, one of whom has a diploma and the other of whom is still in training.

Notes on the sources

The first publication about the Kĩsêdjê was written by a German scientist, Karl von den Steinen (1884). After that, the Kĩsêdjê avoided contact with Europeans and Brazilians until the late 1950s. The first publications about the Kĩsêdjê after their contact with Brazilians were written by Amadeu Lanna (1966) and Harold Schultz (1962). Both authors visited the Kĩsêdjê shortly after they were transferred to the Xingu Indigenous Park in 1959. Schultz concentrated on careful description and photographic documentation of Kĩsêdjê material culture while Lanna analyzed the Kĩsêdjê economic system, history, social organization, and the influence of other groups on their culture.

Anthony Seeger has published three books and dozens of articles on various aspects of Kĩsêdjê life and culture based on more than 24 months living with the Kĩsêdjê, most of those accompanied and assisted by his wife Judith Seeger, and some of them with their daughters Elizabeth and Hiléia. The most complete ethnographic study of the Kĩsêdjê is his book Nature and Society in Central Brazil - the Suyá Indians of Mato Grosso (Seeger 1981). This book analyzes aspects of the Kĩsêdjê cosmology and social and political organization, concepts of space and time, the classification of plants, animals, and humans. The book also covers aspects of mythology, medicine, and other topics. A later book, also in English, focuses especially on music and related performance genres: Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People originally published in 1987 (Seeger 2004, 2nd edition).

In an article entitled "A identidade étnica como processo: os índios Suyá e as sociedades do Alto Xingu," published in Anuário Antropológico no. 78, Seeger describes the history of the Suyá. He describes their relationship with the Upper Xingu communities and the way they have selectively incorporated elements from those groups and from Brazilian national society. He further discusses the mythological importance of how Kĩsêdjê incorporate elements from other communities into their society, which they continue to do. The same subject is raised, with a focus on the writings of Karl von den Steinen about the Kĩsêdjê, in his article "Ladrões, mitos, e história: Karl von den Steinen entre os Suiás 3-6 setembro de 1884" (Seeger 1993).

Also in 1980, Seeger published a collection of articles in Portuguese, Os Índios e nós, estudos sobre sociedades tribais brasileiras (Seeger 1980) in which he describes a number of aspects of indigenous culture, with an emphasis on the Kĩsêdjê. Topics covered include body ornaments, the role of the elderly and the community, musical genres, political leadership, kinship, and an introductory chapter on doing ethnography in the final bibliographic essay on publications about Brazilian Indians.

Sources of information

- ATHAYDE, Simone Ferreira de (Org.). Arte indígena Parque do Xingu : catálogo de divulgação cultural e comercial. São Paulo : ISA ; Canarana : Atix, 2001.

- --------. O projeto Kumana e a experiência da Atix na comercialização de artesanato Kaiabi, Yudjá e Kĩsêdjê em 1998 : Relatório. São Paulo : ISA, 1999. 87 p.

- CARVALHO SOBRINHO, João Berchmans de. A música entre os Kĩsêdjê e os Kayabi : a descrição de cerimoniais. Educação e Compromisso, Teresina : s.ed., v. 6, n. 1/2, p. 35-9, jan./dez. 1994.

- FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal. Da origem dos homens a conquista da escrita : um estudo sobre povos indígenas e educação escolar no Brasil. São Paulo : USP, 1992. 227 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- -------- (Org.). Histórias do Xingu : coletânea de depoimentos dos índios Kĩsêdjê, Kayabi, Juruna, Trumai, Txucarramãe e Txicão. São Paulo : USP-NHII/Fapesp, 1994. 240 p.

- --------. Matemática entre os Kĩsêdjê, Kayabi e Juruna do Parque Indígena do Xingu (1980-84). In: FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal. Com quantos paus se faz uma canoa! : a matemática na vida cotidiana e na experiência escolar indígena. Brasília : MEC, 1994. p.24-37.

- --------. Perícia histórico-antropológica da AI Wawi dos índios Kĩsêdjê. São Paulo : s.ed., 1998. 151 p.

- FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal. Quando 1 + 1 ≠ 2 : práticas matemáticas no Parque Indígena do Xingu. In: FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Org.). Idéias matemáticas de povos culturalmente distintos. São Paulo : Global ; Mari/USP, 2002. p. 37-64. (Antropologia e Educação)

- FRIKEL, P. Migração, guerra e sobrevivência Suia. Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v.17/20, p.105-36, 1969/1972.

- GALVÃO, Eduardo. Diários do Xingu (1947-1967). In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Diários de campo de Eduardo Galvão : Tenetehara, Kaioa e índios do Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1996. p. 249-381.

- GUEDES, Marymarcia. Siwiá Mekaperera-Suyá : a língua da gente - um estudo fonológico e gramatical. Campinas : Unicamp, 1993. (Tese de Doutorado)

- LANNA, Amadeu Duarte. Aspectos econômicos da organização social dos Kĩsêdjê. São Paulo : USP, 1966. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Aspectos econômicos da organização social dos Kĩsêdjê. In: SCHADEN, Egon (Org.). Homem, cultura e sociedade no Brasil. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1972. p. 133-82.

- --------. Economia e sociedades tribais do Brasil : uma contribuição ao estudo das estruturas de troca. São Paulo : USP, 1972. 202 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- LEA, Vanessa R. Parque Indígena do Xingu : Laudo antropológico. Campinas : Unicamp, 1997. 220 p.

- ROCHA, Leandro Mendes. A marcha para o oeste e os índios do Xingu. Brasília : Funai, jun. 1992. 36 p. (Índios do Brasil, 2)

- SCHULTZ, Harald. Informações etnográficas sobre os índios Kĩsêdjê, 1960. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : USP, v.13, p.315-32, 1962.

- SEEGER, Anthony. A identidade étnica como processo : os índios Kĩsêdjê e as sociedades do Alto Xingu. Anuário Antropológico, Rio de Janeiro : Tempo Brasileiro, n.78, p.156-75, 1980.

- --------. Os índios e nós : estudos sobre sociedades tribais brasileiras. Rio de Janeiro : Campus, 1980. 181 p.

- --------. Ladrões, mitos e história : Karl von den Steinen entre os Suiás - 3 a 6 de setembro de 1884. In: COELHO, Vera Penteado (Org.). Karl von den Steinen : um século de antropologia no Xingu. São Paulo : Edusp/Fapesp, 1993. p. 431-43.

- --------. The meaning of body ornaments, a Kĩsêdjê example. Ethnology, s.l. : s.ed., n.14, p.211-24, 1975.

- --------. Nature and society in Central Brazil : the Kĩsêdjê indians of Mato Grosso. Cambridge : Harvard Univ. Press, 1981. 288 p.

- --------. Por que os índios cantam? Ciência Hoje, Rio de Janeiro : SBPC, v.1, n.1, p.38-41, jul./ago. 1982.

- --------. Por que os índios Kĩsêdjê cantam para as suas irmãs? In: VELHO, G. (Org.). Arte e sociedade : ensaios de sociologia da arte. Rio de Janeiro : Zahar, 1977. p. 39-63.

- --------. Singing other peoples' songs. Cultural Survival Quarterly, Cambridge : Cultural Survival, v. 15, n. 3, p. 36-9, ago. 1991.

- --------. The sound of music : Kĩsêdjê song structure and experience. Cultural Survival Quarterly, Cambridge : Cultural Survival, v. 20, n. 4, p. 23-8, 1997.

- --------. Why Kĩsêdjê sing : a musical anthropology of an Amazonian people. Cambridge : Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987. 170 p.

- SIMÕES, Mário E. Os “Txikão” e outras tribos marginais do Alto Xingu. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 14, n.s., p. 76-104, 1963.

- KĨSêDJê, Temptxi et al. Kisêdjê Kapêrê : livro para alfabetização na língua Kĩsêdjê. São Paulo : ISA, 1999. 108 p.

- KĨSêDJê, Temptxi; KĨSêDJê, Kaomi; KĨSêDJê, Petoroti. Vegetação Suiá. São Paulo : ISA, 1998. 38 p.

- VILLAS BÔAS, André. Kĩsêdjê lutam pela preservação de seu território. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 618-21.

- VILLAS BÔAS, Cláudio; VILLAS BÔAS, Orlando. A marcha para o oeste : a epopéia da expedição Roncador-Xingu. São Paulo : Globo, 1994. 615 p.

VIDEOS