Karipuna do Amapá

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- AP 3030 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Creoulo

The Karipuna form part of the complex of indigenous peoples of the lower Oiapoque river, where they are located within wide exchange networks that include Indian and non-Indian families in villages and nearby towns in Brazil and French Guiana. Despite comprising a society with fairly imprecise boundaries, rendered fluid and ill-defined by the continual exchanges, intermarriages and distributions between families, the Karipuna use the expression ‘our system’ to define a set of practices, knowledge and beliefs that they consider their own, encompassing both shamanic and Catholic cosmologies.

Location and population

The Karipuna families form a population of approximately 1,700 people (according to data from 2002), most of whom live by the shores of the Curipi river, an affluent of the Uaçá river, in the north of Amapá state. This forms part of the region of the lower Oiapoque river, close to Cabo Orange, a frontier area between Brazil and French Guiana.

The entire region of the lower Oiapoque, including the basin of the Uaçá river and its affluents, comprises a frontier area in various senses. Frontiers between ocean and river, coast and inland, marsh and forest, the breeze of the ocean winds and the equatorial heat, borders between nations. The populations of the Uaçá living in this region also create, circumvent and recreate specific boundaries, differentiating themselves into ethnic groups, identifying themselves as ‘indigenous peoples of the Oiapoque.’

The size and composition of the Karipuna villages varies enormously, as can be observed in the following list produced by Funai (ADR Oiapoque) In October 2000:

| Villages | Population (in 2002) |

| Manga | 458 |

| Japiim | 29 |

| Paxiubal | 37 |

| Santa Isabel | 238 |

| Taminã | 45 |

| Espírito Santo | 345 |

| Jõdef | 64 |

| Txipidon | 21 |

| Igarapé de Onça | 6 |

| Zacarias | 27 |

| Ghõ Puen | 4 |

| Tauahu | 12 |

| Bastião | 8 |

| Açaizal | 91 |

| Encruzo | 25 |

| Piquiá | 19 |

| Curipi | 38 |

| Kariá | 95 |

| Estrela | 95 |

| Aribamba | 49 |

| Kunanã | 70 |

The only villages not located on the shores of the Curupi river are Piquiá, Curipi, Kariá and Estrela, located along the BR-156 highway, as well as Aribamba on the Oiapoque river, and Kunanã on Juminã creek.

Since October 2002, all these villages have been located within a territory demarcated and ratified by presidential decree as three contiguous Indigenous Territories (ITs): Uaçá IT, with a surface area of 470,164.06 ha; Juminã IT, with 41,601.3 ha; and Galibi IT, which had been ratified since 1982, with a surface area of 6,689.2 ha, where the village of Aribamba is situated.

Language and name

The Karipuna speak Portuguese and Patois, which is the region’s lingua franca, but which presents variations from the patois spoken by other indigenous groups and, principally, the Patois of Caiena.

The term ‘Karipuna’ is used as an autonym by this population and indicates an identity as ‘mixed Indians’ or ‘civilized Indians,’ which is both attributed to and assumed by the Karipuna families.

History

In terms of the general history of the region, it should be emphasized that various indigenous groups sharing occupation of the Oiapoque river – members of the Arawak, Tupi and Carib linguistic trunks – have since the 16th century had contact with Europeans from different nationalities and with differing intentions: French, Portuguese, Dutch and English, and members of missionary, commercial, military and scientific expeditions. Each of these native and foreign groups, in accordance with their size and own interests, established alliances, traded or engaged in war. In this process – which in subsequent centuries was joined by runaway or freed black populations, as well as indigenous groups fleeing persecution – some indigenous groups disappeared, while others combined together, became absorbed into larger groups, or formed new groups. These processes generated the current indigenous peoples of the Uaçá. In particular, the Karipuna population of the Curipi river results from this fusion of diverse ethnic groups.

It was only in the 20th century that the groups of the Uaçá river became familiar with the regular presence of the Brazilian government, along with missionary organizations. This more recent history was fundamental in the development of a joint identity currently shared by these groups. At the same time, according to the different attitudes of each people in relation to the activities of these government and missionary bodies, specific features have become imprinted on their cultures, which are nowadays used as factors for differentiating the groups.

The turn of the 20th century represented a decisive moment for these groups, since the Uaçá river region, disputed with French Guiana, was defined as part of Brazil’s territory. From the 1920s, Brazilian authorities deemed it necessary to implement projects for occupying the formerly contested territory whose ‘frenchified’ populations were seen as a threat to the country’s territorial integrity.

In 1920 the Oiapoque Colonization Commission was created. The Commission undertook a reconnaissance expedition along the frontier and concluded that the region needed to be colonized with 'national elements.’ To the north of Vila Martinica (the current administrative centre of Oiapoque municipality), the commission proposed the construction of the Clevelândia Agricultural Colony, officially founded in 1922, receiving settlers from the Brazilian northeast. In 1924, these families of settlers had to divide their dwellings with 1,630 political prisoners, opponents of Artur Bernardes’s government. The following year, both prisoners and settlers became victims of a serious epidemic and the survivors were transferred to Vila Martinica.

With the failure of the colonization attempt, the government turned its attention to the indigenous populations. In 1927, the Oiapoque river was patrolled by the Frontier Inspection Commission of the Ministry of War, commanded by General Rondon. The reports produced by the Commission mentioned the ethnic groups of the Uaçá basin, citing the same ethnonyms used today, and also indicated the need to create an indigenous post and a school as the first institutions designed to “incorporate the Indians into society.”

It was also in the 1920s that Curt Nimuendaju carried out his research among the peoples of the Uaçá, especially among the Palikur. This work, along with the research in the following decades by Eurico Fernandes (1948, 1950), are the only ethnographic records we have on the Indians of the region in the first half of the 20th century. According to Nimuendaju’s information, Karipúna refers to "a fairly large number” of speakers of the Língua Geral Tupi, fugitives from the missions on the Cunani and Macari who migrated to the Oiapoque at the end of the 18th century, along with Aruãs Indians, after the depopulation of the region by the Portuguese.

In the 1930s there was an increase in the economic exploration of the territory occupied by the Indians. A rosewood (Aniba rosaeodora) extraction plant ran on the Curipi from 1932 to 1935, employing a number of Karipuna, until the wood was exhausted. Gold exploration was conducted primarily by creole populations on the Oiapoque and upper Uaçá rivers. In terms of government policies, three important facts for the Uaçá populations occurred during this decade: the implementation of primary schools in 1934, the 1936 expedition of Luís Thomas Reis, sent to the area as a frontier inspector to assess the possibility of using the indigenous population as ‘border guards,’ and the appointment of Eurico Fernandes, who had already had prior contact with the peoples of the Uaçá, as Inspector of Indians.

The official recognition of the populations of the Oiapoque as part of the category of ‘indigenous peoples,’ which implied the appointment of an Inspector of Indians as an SPI agent, should be understood as a government measure aiming to control this frontier population. The families of the villages were immediately considered ‘Indian,’ with no need to ascertain their cultural traits, as occurs in other regions, notably the Northeast where control strategies focused precisely on denying the ‘indigenous’ condition of local populations.

As cane be gleaned from the Frontier Inspection reports, the need for the school, planned as a school for professional training, was linked to the need to ‘train national workers,’ duly controlled through the construction of an indigenous post that would rely on the 'social and political support' of the military detachment at Clevelândia. Hence, the school project was based on the positivist, nationalist, coercive and authoritarian ideology widespread at the time, the ideological foundation of the Indian Protection Service (SPI) itself.

Summarizing, in 1934 two female teachers were recruited by the government to teach in the Espírito Santo village on the Curipi and at Santa Maria dos Gallibis on the Uaçá (the current Kumarumã village). The schools functioned in the houses of the village chiefs for just three years. In 1945, through the SPI, the school was re-activated on the Uaçá and the Curipi, this time at Santa Isabel village from where the trading establishment of the leader Coco operated.

Although apparently precarious and intermittent, this school education played a fundamental role in formulating the contemporary identity of these groups, in the propagation of the use of Portuguese and in the configuration of the villages. Civic notions such as hoisting the national flag, celebrating September 7th (Independence Day), singing the national anthem and playing football daily were some of the legacies introduced by the school.

From the 1950s, following the departure of Eurico Fernandes, the SPI’s control became less pronounced with a reduction in the number of projects, space for the entry of river traders, less control and even incentives for marriage to non-Indians. As its funding diminished, the SPI’s actions became less effective and the new agent turned to making deals with local politicians, encouraging the electoral enlistment of the Indians and establishing a clientelist politics. The Karipuna became the most heavily involved in this enlistment and soon began to vote in compliance with the indications of their leaders, contradicting those of the SPI agent himself.

In 1962, the same agent entered into an agreement with the Oiapoque Military Colony, authorizing the installation of a buffalo farm on Suraimon island, close to the Galibi village. Various conflicts arose from the implantation of this farm. The creation of Funai in 1967 (officially succeeding the SPI) changed the administrative makeup of the region with the setting up of two indigenous posts: Kumarumã IP and Palikur IP. The Karipuna population continued to be attended by the Encruzo IP until the end of the 1970s when a post was built on the Curipi.

The presence of Cimi, in the persons of Father Nello Ruffaldi and Sister Rebecca Spires, was important for the development of a shared identity among the four indigenous peoples of the Oiapoque river. Through contact with the indigenous villages, Nello Ruffaldi, parish priest of Oiapoque since 1972, adopted the line advocated by Cimi and initiated projects focused on the autonomy of the groups and the valorization of aspects of their cultures (such as the Patois idiom itself). These projects included cementing the trade cooperatives (which achieved some positive results, but ended up closing by the end of the 1980s), encouraging the organization of political assemblies, and developing differentiated education projects. The latter two projects have had increasingly positive results, visible today.

The 1970s, therefore, were marked by greater political participation of the Uaçá leaders, who began to act in more organized fashion. Together they opposed the Suraimon farm (eventually deactivated at the start of the 1980s) and began the process of demanding the demarcation and ratification of their lands. They were heavily pressurized by the government of the territory in 1980 when they opposed the proposed route for the BR-156 highway (Macapá-Oiapoque), fearing the loss of the headwaters of the Uaçá and Curipi rivers. On this occasion, Father Nello Ruffaldi was accused of inciting the Indians and threatened with deportation. The head of the Funai post, Cezar Oda, was dismissed having been accused of divulging ‘subversive’ books and pamphlets. The leaders eventually accepted the route of the highway and signed a term of agreement that promised, among other things, the construction of surveillance posts along the highway and the hiring of indigenous heads to assist in the inspection of the borders of the indigenous territory.

Despite this and other setbacks, which ended up undermining the trust of the families in the leaders who signed the agreement, the process of organizing the leaders and encouraging political participation remained alive. The indigenous assemblies of the Oiapoque, initially promoted by Cimi and stimulated by the heads of post, were increasingly promoted and organized by the Indians themselves. Today they are known across the state of Amapá and considered model examples of organization. As for their participation in the region’s political life, the activities of some leaders, which prior to the 1970s was limited to forging alliances with local politicians, has become more collective and cohesive. In this process, a more generic identity of ‘indigenous peoples of the Oiapoque’ has become visible.

The most positive outcomes of the process of increasing the political participation and autonomy of the indigenous groups became apparent in the 1990s, led by the definitive ratification of the indigenous territories of the Oiapoque in 1992, the creation of the Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the Oiapoque the same year, the qualification of thirteen indigenous teachers on the teacher training course in 1995, and the election of the Galibi-Marworno Indian, João Neves, as mayor of the municipality of Oiapoque in 1996.

These groups, whose earlier generations absorbed the 'civic morality' brought by the school, are today actively pursuing a process of valorizing indigenous traditions, looking to recover their own history and the knowledge they consider traditional.

Social organization

The indigenous peoples of the lower Oiapoque river form part of wider exchange networks that include Indian and non-Indian families living in villages and neighbouring towns in Brazil and French Guiana. The self-recognition as ‘mixed Indians’ expressed by Karipuna families refers to their heterogenic origin, as well as the constant alliances established with foreign individuals or families. Hence the criteria of group belonging depend on agreement with the principles of solidarity and mutual cooperation, encompassing over time persons and families who were initially considered to be ‘from outside.’

The other indigenous groups of the region with whom the Karipuna families live are the Galibi-Marworno, the Palikur and a small Galibi group which migrated from the coast of Guiana and now lives on the Oiapoque river. The Karipuna share with these peoples the features of a broad regional tradition, though they possess their own specificities.

Their marriage choices reveal a high number of alliances between close kin, including nephews, nieces and cousins. These marriages, taken to be incestuous by neighbouring groups, are valorized among the Karipuna since they correspond to the ideal of ‘not spreading the blood.’ In the interethnic marriages there is a tendency for women to marry non-indigenous men, while men tend to seek out wives from other indigenous groups. We can also note the tendency to repeat marriages with people from the same family, even when these come from other indigenous groups. Thus the majority of ‘outside’ spouses end up incorporated into life in the villages with cases of people bringing other relatives to form new marriages.

The two tendencies evident in Karipuna alliance – towards closure, manifested in the endogamy at the level of the extended family, and towards opening, evident in the valorization of marriages with ‘outside’ people – constitute two apparently opposed movements, which nonetheless complement each other in the construction of a singular pattern of social organization. This pattern is also related to the composition of the villages.

The pattern of Karipuna sociability enables the flexibility of the residential pattern, ranging from large villages to small sites sheltering a single nuclear family, without the need to consider one of these forms of residence as ‘typical’ or ‘traditional.’ This is because the basic network of sociability needed to maintain each nuclear family is not so narrow that it is exhausted in the population of a small village, nor so wide that it encompasses the population of a large village. Consequently, the families residing today in small dispersed villages are united with one another, composing a larger circle of exchanges and mutual support, while the families living in large are villages are not equally connected to the entire population but form smaller circles, which generally compose residential sectors within the overall layout of the village. It is within these circles of cooperation and mutual support that we can visualize the constitution of local groups, where the tendency towards endogamy operates.

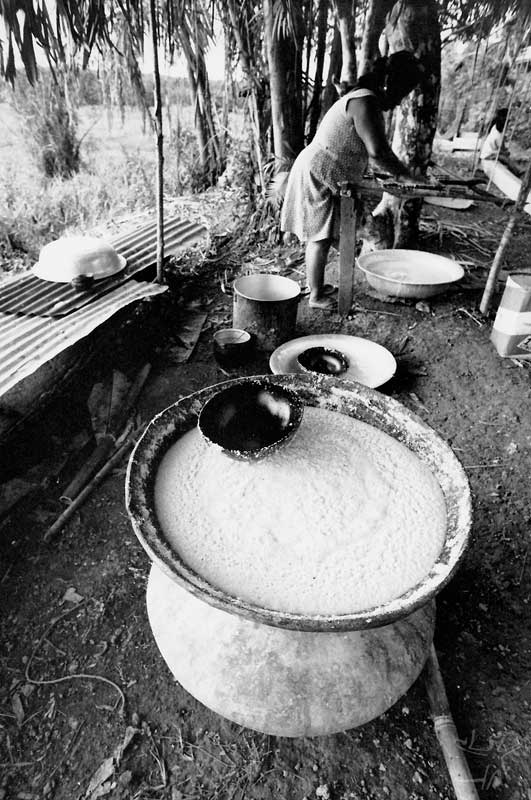

These circles are also the ambit within which people organize the collective tasks that ensure the families’ subsistence: the building and maintenance of houses, or the production of flour for their own consumption and sale, for example. These circles also act together to help a particular nuclear family to offer food and drink in collective planting (which unites a wider community) or a ‘saint festival.’

Cosmology and shamanism

Despite comprising a society with fairly imprecise boundaries, rendered fluid and ill-defined by the continual exchanges, intermarriages and distributions between the families and other villages and neighbouring towns, the Karipuna use the expression ‘our system’ to define a set of practices, knowledge and beliefs that they consider their own, encompassing both shamanic and Catholic cosmologies.

The Karipuna believe that parallel to the reality in which we live, to ‘our world,’ or ‘this time,’ there exist other worlds that they define in abbreviated form as ‘depths,’ or more specifically as ‘depths of the waters,’ or ‘depths of the forest’ or even ‘beneath the Sun.’ This is a present time parallel to our own, but occurring in another dimension.

These different worlds are inhabited by a series of supernatural beings, generically denominated as ‘creatures’ (bet), ‘souls’ (nam), ‘masters’ (met), ‘owners’ (ghãpapa, literally ‘grandfather’) and more specifically as ‘snake,’ ‘monkey,’ ‘cayman,’ banahe, laposinie, and so on. Contact with these beings is always considered dangerous to normal people, liable to cause attacks, death and even make women pregnant. Shamans are the only ones capable of transiting between these worlds, or of evoking and controlling these beings in our world.

The beings populating the worlds of the 'depths of the waters and the forest' are called 'creatures' and are identified by the names of various animals, the most common being: large snakes, caymans, monkeys, swordfish, spoonbills and pigeons. They claim that these beings “are people like us in their world,” where they hold festivals and drink caxiri (fermented manioc drink), and that “they wear their animal coat when they come to wander in our world.” In other words, the snake wears its snake skin, the birds wear their feathers and the animals wear their pelts.

These beings may also be called nam (une âme, ‘soul’), a category that includes “everything that has a spirit,” such as certain trees used for curative purposes during shamanic initiation itself (called arari, apucuriuá, tauén as well as tauari). In these cases, the term does not refer to the souls of dead people. As for the destiny of the dead, the Karipuna believe that their souls “remain hereabouts” and may cause diseases in the living or speed up the death of the sick. They say that the whites do not perceive them, but the Indians can hear the souls when they are nearby, since they emit a high-pitched whistle, which is also produced in the forest by the trees that possess nam.

The name ‘masters’ is given to the beings who, among the categories mentioned, help the shamans during their apprenticeship and in their practices, and in this sense merge with the karuãna of the shamans. The word ‘master’ is also used for the beings who inhabit or look after particular places: ‘master of the creek,’ ‘master of the cavern,’ for which the terms 'mother,' 'owner' and ghãpapa (grandfather) are also used. These terms may be applied to snakes, monkeys and 'creatures' in general, as well as to the hohôs, defined as small beings with long tangled hair, who inhabit rocky areas, caverns and creeks and always walk in pairs – “they are two little brothers” – and who can make women pregnant, making them conceive twins.

The Karipuna say that the ‘masters’ look after the places where they live, always leaving them clean, and may cause sickness in those who pollute these spaces with the strong smell of fish (pitiú) and menstrual blood. However, they also say that these beings are attracted by this blood, through which they can penetrate a woman’s body and make her conceive “animal children” when she ahs sexual relations.

Finally, the designation karuãna refers to all those beings who have a relationship with a particular shaman. As they are continually linked to a shaman, a karuãna may also be called ‘friend’ (zami) or ‘companion’ (kamahad) by him, and is always conceived as an individuality with its own history and personality.

A shaman’s karuãna include ‘creatures,’ such as snakes, caymans, monkeys and birds, and ‘souls’ such as ‘arari’ and ‘tauarí,’ but also different categories of beings, inhabitants of different worlds such as ‘curupiras’ (djab dan bua), ‘devils’ (djab), banahes, and so on. All these categories of beings are attributed with their own capacities, sometimes specific languages, and may also be called by the generic term of ‘creatures of the shaman.’ Every shaman has among his karuãna one that he calls laposinie. This is considered the ‘biggest master,’ the one who teaches the shaman his curative skills and techniques and without whom a shaman is merely capable of casting sorcery. They say that these beings live in the “land beneath the Sun” or in the “world where the Sun rises,” and describe them as “white fine people,” also calling them “good doctors.” The word laposinie (from the French ‘la poussinière’) also refers to the constellation of the Pleiades. Concerning these beings, the Karipuna say that they spend a month every year in another world swapping their skin and take fish and birds with them, making the latter difficult to find.

Rituals

There in the Depths, when the moon is descending over there, beauuuutiful, then the animals are dancing there in the Depths. (...) That’s where we go. (...) That’s where we’ll sing, that’s where we’ll drink, we’ll dance with our animals. (Citation from the shaman Elza, Manga village, 1992).

The Turés are taken by the families of the Curipi as occasions for dancing, drinking and singing along with the supernatural beings called karuãna, and offering them caxiri (fermented manioc drink) as payment for the cures they provide through the shamans. The participants of a Turé correspond to a shaman’s clientele, the group of families who turn to him (or her) when ill. Thus the Turés usually bring together related families who share their trust in a particular shaman and their recognition of the set of supernatural beings that are considered the zami (friends), kamahad (companions) or karuãna of this shaman.

Centred on the figure of the shamans, each Turé manifests the particularities of its own universe of karuãna. It is believed that the ‘strongest’ shamans manage to assemble a larger number of karuãna, who teach them many Turé songs and are thus able to chant for several nights without repeating a single song. The force coming from the karuãna also allows them to diagnose illnesses properly and cure them successfully, meaning that there are many people to help make caxiri (the relatives of the sick repay the cure given by the shaman’s karuãna by offering them fermented this drink) in the Turé of a ‘strong’ shaman, and the dancing lasts many nights.

The Karipuna prefer to perform Turés on a weekend with a full moon in the month of October, which marks the end of the dry season, just before the first rains. However numerous contingencies may alter this ideal date, including the attempt to avoid various Turés being held on the same day. Hence the shamans also hold the festivals on moonless nights, using lamps for lighting, until the beginning of December, if the rains hold off that long. Even those villages with electricity generators use the lamps during Turés, since the karuãna dislike the noise. There are Turés, however, that take place on certain festive days, such as the National Indian Day, or during celebrations in neighbouring towns. These are considered ‘demonstrations’ rather than occasions for celebrating with the karuãna.

The preparation for a Turé begins far in advance, as occurs too with the ‘Saint festivals.’ At the end of a Turé, after the shaman’s speech, a group of men proposes to help him the following year with the gesture of carrying the masts of the Turé on their back. These men are called tet dãse (heads of the dance) and must help the shaman with all the preparations, as well as helping enliven the festival, playing the flutes, singing and leading the dances.

The shamans interviewed claim that the lengthy preparation for the Turé takes place through dreams during which they travel to ‘the Depths’ or to ‘other worlds,’ where they take part in Turés with their karuãna, also called ‘creatures.’ These dream rituals inspire the shamans to organize their Turés ‘in this world:’ there they learn the paint designs for the stools and masts, the layout of the dance area, called laku, as well as new songs. The latter are also taught by their karuãna, meaning that each melody is conceived to be particular to each shaman, signs of his contacts with the karuãna. ‘Imitating’ another shaman’s songs is heavily frowned upon.

Based on these dreams, therefore, the shamans arrange the laku, which is bordered by bamboo, and the piroro, within which the decorated stools and masts are placed. To help with arranging these spaces, he invites the tet dãse, generally one or two months in advance, the time needed to male the stools, masts and body decorations: feather headdresses, necklaces, dorsal adornments and rattles.

As well as the explanations and practices of the shamans, the Karipuna also make use of Catholic resources in the form of prayers, pledges and litanies. The saint festivals are commemorated at various points on the Curipi river throughout the year and take the ‘Grand Festival,’ the Divine Holy Spirit, as their model.

The festival of the Divine

The festival of the Divine is taken by the Karipuna to be their largest festival, la Ghã fet, as they say in Patois. This involves two weeks of festivities, uniting in the Espírito Santo village all those who consider themselves part of the ‘Curipi community.’ The other villages empty during this period, since almost all the families living on the Curipi travel to the Espírito Santo village to celebrate. Other people who consider themselves Karipuna but reside outside the Curipi, whether in other villages on the Uaçá or Oiapoque rivers, or in the neighbouring towns of Oiapoque and Saint Georges, also head to the Curipi on this occasion. Likewise people living in towns further away, such as Caiena, Macapá or Belém in Pará state, return from time to time to take part and make a pledge to the Divine. Hence it is in the Grand Festival that one can visualize in a joyful and dynamic form what is usually difficult to find on other moments of the group’s life, since it is in the festival that Karipuna ‘society’ takes shape.

The Grand Festival follows the Catholic calendar. On a Thursday during May the ascension of Jesus Christ to heaven is celebrated, which is when the mast of the Divine is raised. Ten days later Pentecost, the descent of the Holy Spirit is celebrated and the mast brought down. The most important and lively festivities take place on this second occasion. A series of preparatory and closing activities surround these two dates, meaning that the festivals of the Divine begin a long time before Ascension Thursday and finish after Pentecost Sunday. Between the two dates, there is a short period of five to seven days when the families return to their villages and resume their day-to-day work.

The Saturday prior to the Ascension is the day of Maiuhi Xapel or ‘Chapel Guest.’ At dawn, rockets are set off to announce the start of two days of festival. Around eight o’clock the bells of the chapel are played and the Festival House begins to fill. Some women take turns in the kitchen, preparing the meal or straining the caxiri. The men also help by cleaning the fish and freshest game. The festival sponsors busy themselves serving drink to everyone. Gradually men and women begin the work of clearing the terrain where the participants will be welcomed.

On the Wednesday, a team of festival goers leaves the village in search of a tree trunk to make the mast of the Divine and at night the first dance begins, which is interrupted at midnight for the first Litany. Everyone moves to the chapel and, after prayer, form a line to kiss the ribbons of the Holy Spirit on the alter and the other saints. Afterwards everyone returns to the dance, which continues until daybreak.

On the Ascension Thursday the mast is raised and another day ensues of plentiful food, drink, songs and dances. Nine days after Ascension, on the Saturday before Pentecost, the festival foes once again announce dawn with rockets. And once again the village of Espírito Santo begins to fill and become lively with rockets announcing the arrival of boats from other villages.

The eve of the Pentecost is the day of the Half-Moon procession when various boats and canoes head off to the small island where the cemetery is located. The procession walks down the slope from the village with children at the front, followed by women, all of them carrying candles; they are followed by the men, some bearing flags, others carrying the float of the Divine, heavily decorated with streamers and flowers. Finally, the musical band – small guitar, guitars, viola e violin – play various religious pieces to ‘accompany the saint.’ The float of the Divine, flag-bearers band and ‘pledgers’ board a covered boat. The ‘saint boat’ is accompanied by various canoes and river boats, which nestle against each other, offering drink during the journey. As they approach the Karipuna cemetery, the band stops playing and the string instruments give way to the drums, which accompany the song of the cemetery. The boats circle twice in front of the cemetery and return to the village, where they circle twice more before landing. There they sing the Song of the Arrival of the Half-Moon.

A final chant, the Song of the Entry of the Full Moon, is sung in front of the chapel where the entire assembly heads, accompanied by the Divine. After the prayer, the events unfold in the same form as the eve of Ascension: the songs at six o’clock in the evening, litany at midnight, much food and drink, the welcoming of the festival goers in the dance hall and the lively dancing until dawn.

The next day, when the day of the Descent of the Holy Spirit is commemorated properly-speaking, they also perform the Dawn song and the six o’clock morning songs. Before lunch they prepare the Table of the Innocents, a meal solemnly served to the children, who arrive at the location in procession.

At the end of the afternoon begins the ceremony for felling the mast. As in the previous festival, the children are summoned by the bell to climb up to the chapel and head off to the mast in a small procession. A boy climbs the mast and removes the flag of the Divine. Next, using an axe decorated with coloured ribbons, each festival goer chops the mast to fell it.

The music in the Festival House is only interrupted as night falls and the village leader asks who will be willing to sponsor the festival next year. And so the festival reaches its conclusion, with the pledge to begin again the following year.

Further reading

For a detailed description and analysis of the Turés and the Festival of the Divine among the Karipuna, see the book by Antonella Tassinari, No bom da festa: o processo de construção cultural das famílias Karipuna do Amapá. São Paulo: Edusp, 2003.

Productive activities

Fishing is abundant on the rivers of the Uaçá basin, especially during the dry season. Fish include trahira, laulao catfish, golden trahira, piranhas, silver arowana, cará, peacock bass and arapaima and, on the lower Curipi and Uaçá, as well as the lower Oiapoque, numerous salt-water fish. Some ocean species are fished at sea, including the highly prized crabs. People fish along these rivers all year for caymans and turtles.

The vegetation varies along the rivers according to the presence of floodplains or terra firme. On the lower courses, marshy plants are abundant, forming mangrove swamps and flood forests. Further upriver are found the large floodplains, interspersed with small islands of high ground covered in terra firme forest, the ‘tesos,’ where villages are built and swiddens cleared. This landscape is also known as ‘savannah’ and populated with herons, storks, maguaris, geese and wild ducks. The larger tesos also provide the hunting ground for deer, tapir, pacas, agoutis, monkeys, peccaries and coatimundis. Further south, close to the headwaters of the rivers and as far as the middle Curipi, the marshy fields give way to terra firme vegetation, comprising forests used for hunting or extracting timber (primarily utilized to make oars and canoes). This area of terra firme was the region chosen in the 1970s for the construction of the BR-156 highway, linking the town of Oiapoque to Macapá.

During the dry season the families work at clearing the new swiddens. The men work in groups to fell the trees and clear the terrain from August to September and wait for strong sunshine to set fire to the land. On this occasion, meat and eggs from chameleons found in the burnt forest form part of the menu. By October and November when the first rains fall, the swiddens are ready for planting, again undertaken in large animated groups.

Sources of information

- ARNAUD, Expedito. Os índios da região do Uaçá (Oiapoque) e a proteção oficial brasileira. In: --------. O índio e a expansão nacional. Belém : Cejup, 1989. p. 87-128. Publicado originalmente no Boletim do MPEG, Antropologia, Belém, n.s., n. 40, jul. 1969.

- ASSIS, Eneida Corrêa. Escola indígena, uma “frente ideológica”? Brasília : UnB, 1981. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. As questões ambientais na fronteira Oiapoque/Guiana Francesa : os Galibi, Karipuna e Paliku. In: SANTOS, Antônio Carlos Magalhães Lourenço (Org.). Sociedades indígenas e transformações ambientais. Belém : UFPA-Numa, 1993. p. 47-60. (Universidade e Meio Ambiente, 6)

- CASTRO, Esther de; VIDAL, Lux B. O Museu dos Povos Indígenas do Oiapoque : um lugar de produção, conservação e divulgação da cultura. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 269-86. (Antropologia e Educação)

- DIAS, Laercio Fidelis. Curso de formação, treinamento e oficina para monitores e professores indígenas da reserva do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.359-78. (Antropologia e Educação)

- --------. Uma etnografia dos procedimentos terapêuticos e dos cuidados com a saúde das famílias Karipuna. São Paulo : USP, 2000. 263 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. As práticas e os cuidados relativos a saúde entre os Karipuna do Uaça. Cadernos de Campo, São Paulo : USP, v. 10, n. 9, p. 59-72, 2000.

- MUSOLINO, Álvaro Augusto Neves. A estrela do Norte : Reserva Indígena do Uaçá. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. 242 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- TASSINARI, Antonella Maria Imperatriz. No bom da festa. O processo de construção cultural das famílias Kripuna do Amapá. São Paulo : Edusp, 2002.

- -------. Contribuição à historia e à etnografia do Baixo Oiapoque : a composição das famílias Karipuna e a estruturação das redes de trocas. São Paulo : USP, 1998. 366 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Da civilização à tradição : os projetos de escola entre os índios do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.157-95.

- --------. O processo de construção cultural das famílias Karipuna no Amapá. São Paulo : Edusp, 2003.

- --------. Xamanismo e catolicismo entre as famílias Karipuna do Rio Curipi. In: WRIGHT, Robin (Org.). Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 447-78.

- TOBLER, S. Joy. The grammar of Karipúna creole. Brasília : SIL, 1983. 156 p.

- VIDAL, Lux B. O modelo e a marca, ou o estilo dos “misturados” : cosmologia, história e estética entre os povos indígenas do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.196-208.

- --------. O modelo e a marca, ou o estilo “misturador” : cosmologia, história e estética entre os povos indígenas do Uaçá. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 42, n. ½, p. 29-45, n.esp., 1999.

- --------; SILVEIRA, Luís Fábio; LIMA, Renato Gaban. A pesquisa sobre a avifauna da bacia do Uaçá : uma abordagem interdisciplinar. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.287-58. (Antropologia e Educação)