Karajá

- Self-denomination

- Iny

- Where they are How many

- GO, MT, PA, TO 4373 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Karajá

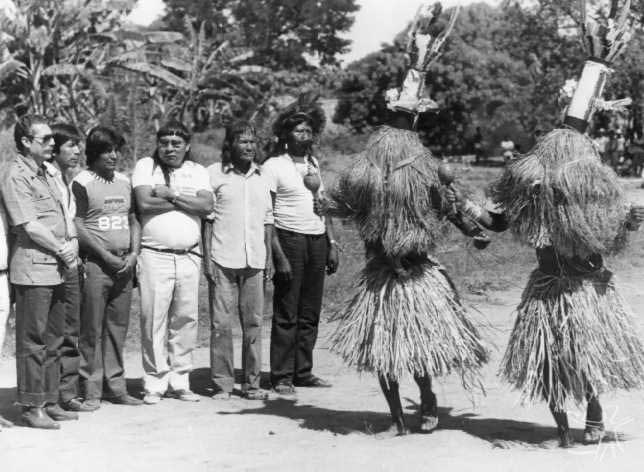

Inhabitants for centuries of the shores of the Araguaia river in the states of Goiás, Tocantins and Mato Grosso, the Karajá who today live in various villages have a long history of contact with non-Indian society. Yet this has not prevented them from maintaining many of their traditional customs such as: their native language, their ceramic dolls, domestic fishing trips, rituals such as the Aruanã Festival and the Big House (Hetohoky) Festival, feather decorations, basketry and craftwork made from wood, as well as body painting such as the distinctive two circles designed on the face. At the same time, they look to spend temporary periods in towns as a way of acquiring the means to fight for their rights such as demarcation and preservation of their lands, and access to healthcare and bilingual education.

Name

The name of this people in their own language is Iny, meaning ‘us.’ The name Karajá is not an original auto-denomination. Rather, it is a Tupi name that can be roughly translated as ‘large monkey.’ Although uncertain, the earliest sources from the 16th and 17th centuries already use the spelling ‘Caraiaúnas’ or ‘Carajaúna.’ In 1888 Ehrenreich proposed the form Carajahí. However in 1908 Krause settled the confusion of names by fixing the spelling as Karajá.

Language

According to the linguist Aryon dall’Igna Rodrigues, the Karajá family belongs to the Macro-Gê linguistic trunk and divides into three languages: Karajá, Javaé and Xambioá. Each of these possesses distinctive forms of speech depending on the sex of the speaker. But despite these differences everyone understands each other. Due to the process of contact with non-indigenous society, Portuguese has become dominant in some villages such as Xambioá (Tocantins) and Aruanã (Goiás).

At the start of the 1970s, Funai adopted a bilingual and bicultural educational program for some groups, including the Karajá. This program was directed by the Summer Institute of Linguistics, an entity which also has religious aims. It resulted in the translation of the Bible into the Karajá language.

Location

The Araguaia acts as a mythic and social axis for the Karajá. The group’s territory is defined by an extensive stretch of the Araguaia river valley, including the world’s largest fluvial island, the Ilha do Bananal, which measures approximately two million hectares. Their 29 villages are located by preference close to the lakes and affluents of the Araguaia and Javaés rivers, as well as inland on the Ilha do Bananal. Each village establishes a specific territory for fishing, hunting and ritual practices, internally demarcating cultural spaces recognized by the whole group.

This displays the high degree of mobility among the Karajá, one of whose cultural traits is exploration of the food resources along the Araguaia river. Today, they still follow the custom of camping with their families in search of the best spots for catching fish and turtles, in lakes and on the river’s tributaries and beaches, where in the past they built temporary villages These were often the scene for festival performances during the dry season period when the Araguaia fell to its lowest. With the arrival of the rains, they moved to villages built on the higher cliffs, safe from the rising water level. Some of these sites are still used for their domestic and collective swiddens, dwellings and cemeteries.

The legal status of the lands belonging to the Karajá subgroup is as follows:

- The Araguaia Indigenous Park (Ilha do Bananal) - total area of 1,358,499 hectares, demarcated, approved and awaiting registration (Funai 1998).

- Aruanã Karajá - Area I (Goiás) with 11 hectares, Area II (Mato Grosso) with 769 hectares and Area III (Goiás) with 586 hectares, in process of demarcation (Funai 1998).

- São Domingos with 5,705 hectares in Luciara municipality, Mato Grosso, approved.

- Maramanduba with 26 hectares in Santana do Araguaia municipality, Pará, under revision.

- TI (Terra Indígena = Indigenous Land) Tapirapé/Karajá, Mato Grosso, approved.

Demography

An idea of the group’s population numbers may be obtained from the following years and data:

| Karajá | Javaé | Xambioá | Total | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| --- | --- | --- | 7,000 a 8,000 | 1775 | Fonseca, 1920 |

| 815 | --- | --- | --- | 1908 | Krause, 1908: 238 |

| 795 | --- | --- | --- | 1939 | Lipkind, 1948: 180 |

| 1.406 | --- | --- | --- | 1980 | Toral, 1992: 27 |

| 1.588 | --- | --- | --- | 1990 | Toral, 1992: 41 |

| 1.900 | 750 | 250 | 2.900 | 1995 | ISA, 1996: vii |

| ±1.500 | ±841 | 202 | ±2.593 | 1997 | Braggio, 1997 |

Despite the intense contact with non-indigenous Brazilian society, an increase in population size has been registered among those Karajá who continue to live in their traditional territory. The villages of each subgroup are distributed in the following way:

The Karajá subgroup is formed by the Aruanã community (Goiás) which numbers approximately 50 people (more recent data indicates that this village took in another section of the Karajá following land demarcation and now totals some 70 people), by the villages of Isabel do Morro, Fontoura, Macacúba and São Raimundo on the western half of the Ilha do Bananal, by smaller villages such as São Domingos and also by two small villages close to the Tapirapé river, as well as small groups located below the northern tip of the island, totalling approximately 1,500 people (Braggio 1997).

The Javaé subgroup on the shores of the Javaés river (a branch of the Araguaia circling the eastern shore of the Ilha do Bananal) and in the island's interior comprises about 841 people, distributed in six communities in the municipalities of Formoso do Araguaia, Cristalândia and Araguaçu (Braggio 1997).

The Xambioá subgroup has two villages with 202 individuals (Braggio 1997) on the lower Araguaia.

Contact history

Historical studies tell us that the Karajá were once at war with other indigenous peoples such as the Kayapó, Tapirapé, Xavante, Xerente, Avá-Canoeiro and, less frequently, the Bororo and Apinayé, as they sought to protect their territory. This contact led to an exchange of cultural practices between the Karajá, Tapirapé and Xikrin (Kayapó).

The second wave of contact is related to the São Paulo 'bandeirantes' (adventurers) exploring areas to the mid-west and north of Brazil, such as the expedition made by Antônio Pires de Campos, estimated to have taken place between 1718 and 1746. After these, various other expeditions visited the Karajá over the years: the latter were thus forced into almost continuous contact with Brazilian society.

Their villages became easy targets for innumerable religious fronts, governmental plans, visits from presidents of the Republic such as Getulio Vargas (1940) and Juscelino Kubistchek (1960), construction of a luxury tourist hotel and innumerable visits from researchers, writers and journalists who returned to their cities with cultural objects, such as feather work artefacts, paddles, and the traditional clay dolls made by women. This was the case with the German ethnographer Fritz Krause (1908), the North American ethnographer William Lipkind (1938), the writer José Mauro de Vasconcelos (during the 1960s) and the governors of Goiás, Henrique Santillo (1988) and Tocantins, Siqueira Campos (1989).

The process of permanent contact between the Karajá and Brazilian national society led to their adoption of many of the surrounding society's cultural goods (for example: foods, language, habits, education, and religion). The group's cultural complexity is often invisible to non-indigenous eyes when visitors first encounter the scars left by contact: tuberculosis, alcoholism and malnutrition, all of which increase the prejudices of the rural and urban populations in the region.

Nonetheless, the Karajá demonstrate a vigorous resistance in preserving their main cultural traits, which enable them to negotiate outside contact and keep alive their sociocultural organization and indigenous identity, without abandoning their Brazilian citizenship: they even participate as councillors in the towns along the Araguaia river.

The cicle of life

Among the Karajá, the birth of a child is marked socially by the teknonymy rule: the parents cease to be called by their own names and become known as x's father or x's mother. In the man's case, the new father enters another male grade. The man is taken to be responsible for fertilization. Various copulations are needed to form the child gradually in the mother's womb, which is considered simply a receptacle. After birth, the new-born is washed with warm water and painted with red annatto dye.

During infancy the child's time is spent mostly with its mother or grandmothers. However, the difference between the sexes becomes more evident when the boy reaches the age of seven or eight and has his lower lip pierced with howler monkey bone. Later - when he reaches an age range between ten and twelve years - the boy takes part in a large male initiation festival called Hetohoky or Big House. The boys are painted with bluish-black genipap and remain confined for seven days in a ritual house called the Big House. Their hair is cut and the boy is called jyre or giant river otter.

During her first menstrual period, the girl is looked after by her maternal grandmother and remains confined in isolation. Her public re-appearance, when she is elaborately decorated with painted body designs and feather adornments in order to dance with the Aruanãs, is highly esteemed by men.

Ideally, a marriage is arranged by the couple's grandmothers, preferably from the same village, once the young spouses are able to have sexual relations. However, the most common marriage simply involves the boy going to the girl's house, an event which may be precipitated if one of her male kinsfolk surprises the couple during a secret encounter. Once married, the man goes to live in his wife's mother's house following the matrilocal rule. When the family becomes numerous, the couple constructs their own house as an annex to the house they left, spatially manifesting the extended family. Thus, the oldest woman assumes a central role within the domestic unit, while a man as he becomes older loses his political prestige in the men's plaza, though in compensation he becomes a focus of spiritual power, normally performing shamanic activities.

In Karajá burials, the deceased is placed with his or her belongings in a mat at the bottom of a trench; the grave is covered with poles, reminiscent of a house, in front of which is placed a kind of small mast made from decorated timber. In the past a second burial was also performed which involved exhuming the corpse and placing the bones in a ceramic vase, especially prepared by the deceased's kin. This practice no longer takes place.

Man and women

The Karajá establish a large social division between the genders, socially defining the roles of men and women as foreseen in myths.

Men are responsible for defending the territory, clearing swiddens, domestic and collective fishing trips, the construction of dwellings, formalized political discussions in the Aruanã House or the men's plaza, negotiations with non-indigenous Brazilian society and the performance of the principal ritual activities, since they are equated symbolically with the important category of the dead.

Women are responsible for the education of children until the age of initiation for boys and in a permanent way for girls, focusing here on domestic tasks such as cooking, collecting swidden products, arranging the marriage of children (normally managed by grandmothers), the painting and decoration of children, girls and men during the group's rituals, and the manufacture of ceramic dolls, which became an important source of family income in the aftermath of contact. On the ritual plane, women are responsible for the preparation of foods for the main festivals and for the affective memory of the village, which is expressed through ritual wailing of a special form when someone becomes ill or dies.

The Karajá prefer monogamy and divorce is censured by the group. If a married man's infidelity becomes public, the male kinsfolk of the abandoned woman strike the offending man in front of the entire village in dramatic fashion - an event which can rapidly escalate by provoking heated exchanges between the involved domestic groups: this may even result in the burning of the house of the offending husband's family. Women with a public sexual life, once married and with their own domestic units, cease to be exposed to the community's disapproving comments, since starting a family is an important cultural aspect for the Karajá.

The village

The village is the basic unit of social and political organization. Decision making is made by male members of the extended families, who discuss their positions in the Aruanã House. Factional rivalry between groups of men disputing political power in the village is common. As a result of contact, one of the village's men is elected 'chief' and is held responsible for tackling political issues with external agents, such as FUNAI, universities, NGOs, state governments and so on.

The Karajá also have an intriguing chiefdom which in the past seems to have had two functions: one ritual, the other social. A child - male or female - was chosen by the ritual chief from among those related to him on his paternal side to be educated as his successor. Today, both the ritual chief and the chosen child still receive the same indigenous names: ióló and deridu.

Political disputes between villages are also common, but maintaining solidarity between them - motivated in the past by wars against other ethnic groups and nowadays by the struggles to demarcate their lands and remove illegal land squatters and farmers from the Ilha do Bananal - is reinforced by the rituals which stimulate and celebrate the meetings between villages.

Subsistence activities

The community's staple food sources are the fish populations found in the Araguaia river and the lakes. A few mammals are prized as game, while the Karajá display a special predilection for capturing macaw parrots, jabiru storks and spoonbills to make feather decorations.

Swiddens are cleared in gallery forest using a slash-burn technique. The ethnographic and historical records cite the cultivation of maize, manioc, potato, banana, watermelon, yam, peanuts and beans. Today, easy access to the town's facilities has reduced these products to maize, banana, manioc and watermelon. The Karajá also exploit wild fruits, such as those of the oiti and pequi trees, and collect wild honey. Sometimes they capture livestock raised in the open on the Ilha do Bananal to consume their meat, though this is not much favoured by older people.

Art and material culture

Karajá material culture includes house building techniques, cotton weaving, feather decorations, and artefacts made from straw, wood, minerals, shell, gourds, tree bark and pottery.

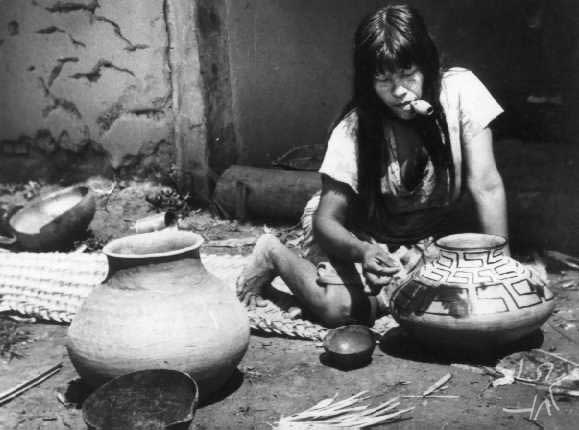

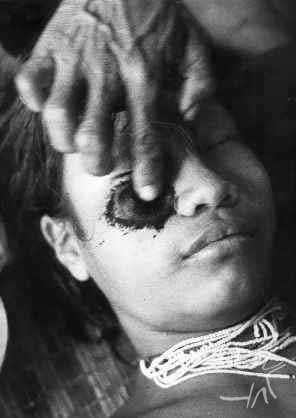

Body painting is symbolically important to the group. During puberty, adolescents of both sexes used to receive omarura, two circles tattooed on their faces: a mixture of genipap and charcoal soot was applied to the blood-covered face cut with payara fish teeth. In response to the prejudice of populations in riverside towns such as São Félix do Araguaia, adolescents nowadays just paint the two circles during the ritual period. Body painting is undertaken by women. Men are painted with different designs, depending on their age grades, using genipap juice, charcoal soot and annatto dye. Some of the more common patterns are black stripes and bands on the arms and legs. The hands, feet and face are painted with a small number of designs representing natural species, especially fauna (Fénelon Costa, 1968).

Baskets are made by both men and women. They feature woven motifs reminiscent of Greek designs and inspired by fauna with animal body parts (Taveira, 1982).

Ceramic art is exclusive to the women, displaying a highly diverse range of kinds and motifs, from domestic utensils such as pots and plates, to dolls with mythological, ritual, quotidian and zoomorphic themes.

The ceramic dolls made by the Karajá are the focus of intense interest from tourists who visit the villages, especially during the season when beaches are exposed along the Araguaia river (July, August and September): as a result, the dolls have become another means of subsistence for the group. Currently only the Karajá sub-group manufactures the dolls. An activity unique to women, these ceramic figures function now as in the past as children's toys: however, they also act as a device for the socialization of girls, a topic covered in a study by Heloisa Fenélon Costa (1968), by modelling dramatizations of events in everyday life. Contact has brought about modifications to the size (becoming larger) and the materials employed, including the use of industrial paints. However, the figurative motifs and decorative patterns are retained by the younger potters, who in fact accentuate figures from myths and rituals. It is very common to find Karajá dolls in craft stores or museums in the towns.

Feather decorations are very elaborate and possess a direct relationship to rituals. Now that macaw parrots - highly prized birds for the Karajá - are more difficult to capture, the variations previously seen in this art form have decreased, leaving only a few decorations such as the lori lori and aheto designs, widely used in the boys' initiation ritual.

Cosmology, mythes and rituals

The Karajá origin myth tells that they used to live in a village at the bottom of the river, where they lived and formed the community of the Berahatxi Mahadu, or the underwater people. Fat and content, they inhabited a cold and confined space. Interested in finding out about the surface world, a young Karajá man found a passage, inysedena, the place of our people's mother (Toral, 1992) in the Ilha do Bananal. Fascinated by the beaches and abundance of the Araguaia river and by the existence of so much space to wander and live in, the youth summoned other Karajá and they ascended to the surface.

Some time later they met sickness and death. They tried to return, but the passage was blocked and guarded by a giant snake at the orders of Koboi, chief of the underwater people. So they decided to spread out up and downriver along the Araguaia. Through the mythological hero Kynyxiwe who loved among them, they came to know about fish and many other good things of the Araguaia. After many adventures, the hero married a young Karajá woman and went to live in the village in the sky, whose people, the Biu Mahadu, taught the Karajá how to make swiddens.

There is a symbolic correspondence between the vertical distribution of the above mentioned mythic peoples and the actual Karajá villages along the Araguaia river valley. The Xambioá are the Iraru Mahadu, the Downriver People, to the north of the Araguaia. The Karajá on the southern tip of the island and the Aruanã are some of the representatives of the Upriver People, or Ibóó Mahadu, while the Javaé according to some authors are the Midriver People or Itua Mahadu (Petesch, 1986 and Rodrigues, 1993). This distribution of the Karajá villages along the Araguaia also corresponds to the distribution of houses in a single village, such as Santa Isabel for example, whose houses form two straight parallel lines. If we imagine these two parallel lines of houses cut by two transversal lines, three segments are formed: the upper houses (upriver), the middle houses and the lower houses (downriver).

In the male initiation ritual, known as Hetohoky or Big House, the men also divide into high, low and middle men: equally, the spatial layout of the ritual houses involves the small house (downriver), the big house (upriver) and the Aruanã house, which is always located in the middle of the other two. The locations of Karajá villages possess a rationale for being at a particular spot in relation to the Araguaia, mirroring the layout of the dwelling houses, the cemeteries, the ritual houses, each following a specific Karajá cultural symbolism.

Myths approach highly diverse themes such as (among many others): the origin, extermination and resumption of the Karajá, the origin of agriculture, deer and tobacco, the origin of rain, the origin of the sun and moon, the Aruanã origin myth, the warrior women, and the origin of Whites. Normally these myths are associated with rituals and social themes, such as gender roles, marriage, shamanism and political power, illness and death, kinship, swiddens, fishing trips and contact with Whites.

The Karajá ritual structure is based around two major rituals: the male initiation rite (the Hetohoky), and the Aruanã Festival. These follow annual cycles based on the rise and fall of the Araguaia river level. The many smaller rites include collective fishing with timbó poison, the honey festival, the fish festival, as well as numerous others interspersed in the main Aruanã and Hetohoky rituals.

Notes on the sources

The references on the Karajá amount to approximately 900 titles (860 of which are found in the famous Bibliografia Crítica da Etnologia Brasileira by Herbert Baldus); owing to the ease of navigating the Araguaia river during the high water season, they have been visited frequently by journalists, travellers, missions, government agencies, photographers and researchers.

Among the earliest ethnographic texts is the rich description made by Paul Ehrenreich, who visited the Karajá in 1888 after participating in Karl von den Steinen's second voyage to the upper Xingu. First published in Berlin in 1891, his work was translated into Portuguese by Egon Schaden and published with an introduction and notes by Hebert Baldus in 1948, with the title 'Contribuições para a Etnologia do Brasil,' which begins with the section devoted to 'As tribos Karajá do Araguaia (Goiás).' Following this work, we have the trustworthy account by Fritz Krause, who travelled along the Araguaia in 1908 and published 'Nos sertões do Brasil.' After these German pioneers comes the North-American anthropologist William Lipkind, who published his ethnography of the Karajá in 1948, based on field work undertaken in 1938 and 1939. It is worth noting that Herbert Baldus, who at the time was dedicated to studying the Tapirapé, visited the Karajá in 1935 and 1947 during his journeys on the Araguaia river: he wrote three articles that included data on the Karajá collected by himself: 'Mitologia Karajá e Tereno,' where the myths of the Karajá occupy most of the work; 'A mudança de cultura entre os índios do Brasil;' and 'Tribos da bacia do Araguaia e o Serviço de Proteção aos Índios.'

In the 1920s and 1930s, a number of São Paulo based expeditions, including journalists, photographers and explorers, travelled along the Araguaia river heading towards the Serra do Roncador and the Karajá were frequently visited and reported. In 1954, the archaeologist Mário Ferreira Simões studied pottery from the Karajá villages: his results can be found in Cerâmica Karaja e Outras Notas Etnográficas (1992).

Modern ethnographies began with Maria Heloísa Costa Fénelon's 1968 thesis on Karajá art and artists. In 1982, Edna Luiza Taveira de Melo published her M.Phil. thesis Etnografia da Cesta Karajá. In the same year, George R. Donahue Junior presented his doctoral thesis at the University of Virginia, providing a general overview of the Karajá. In 1987, the French anthropologist Nathalie Petesch put forward a proposal to classify the Karajá within the ethnological panorama of Central Brazil, while in 1991 Manuel Ferreira Lima Filho completed his M.Phil. thesis at the University of Brasília on the boy's initiation rite among the Karajá. Another three important theses on the Karajá also appear after this date: an M.Phil. by André Amaral de Toral (1992) at the National Museum (Rio de Janeiro), with a wider ethnography on the Karajá; Nathalie Petesch's doctorate at the University of Paris X in the same year; and the M.Phil by Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues, who studied gender among the Javaé at the University of Brasília in 1993.

Finally, it is important to highlight the anthropological evaluations of the effects on the Karajá caused by construction of the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway, contained in the FADESP report dated October 1999.

Sources of information

- AZAMBUJA, Elizete Beatriz. O índio Karajá no imaginário do povo de Luciara-MT. Campinas : Unicamp, 2000. 144 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BALDUS, Herbert. Mitologia Karajá e Tereno. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. 2a. ed. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 108-59. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. A mudança de cultura entre os índios do Brasil. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. 2a. ed. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 160-86. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. Tribos da bacia do Araguaia e o Serviço de Proteção aos índios. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 137-68, 1948.

- BONILA JACOBS, Lydie Oiara. Reproduzindo-se no mundo dos brancos : estruturas Karajá em porto Txuiri (Ilha do Bananal, Tocantins). Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BRAGA, André Garcia. A demarcação de terras indígenas como processo de reafirmação étnica : o caso dos Karajá de Aruanã. Brasília : UnB/DAN, 2002. (Monografia de Graduação)

- BRESIL : Arts prehistoriques, la conquete portugaise et l'art baroque, cultures indiennes, de l'esclavage a l'ere industrielle. Paris : SFBD Archeologia, 1992. 77 p. (Dossiers d'Archeologie, 169)

- BRIGIDO, Suely Ventura. A poética dos ritmos e dos movimentos caóticos : uma leitura do espaço e do tempo, a partir dos conteúdos estéticos e culturais dos índios Karajá. Rev. da Academia Nacional de Música, Rio de Janeiro : Academia Nacional de Música, n. 11, p. 61-76, 2000.

- BUENO, Marielys Siqueira. Macaúba : uma aldeia Karajá em contato com a civilização. Goiânia : UFGO, 1975. 92 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CHIARA, Vilma. Les poupées des indiens Karajá. Paris : Université Paris X, 1970. 175 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- COMASTRI, Elane R. Martin et al. Plano de Manejo : Parque Nacional do Araguaia. Brasília : Ministério da Agricultura/IBDF/FBCN, 1981.

- CONRAD, Rudolf. Weru Wiu : musik der maske weru beim Aruana-Fest der Karaja-Indianes, Brasilien. Bulletin de la Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, Genebra : Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, n. 61, p. 45-61, 1997.

- COSTA, Maria Heloisa Fénelon. A arte e o artista na sociedade Karajá. Brasília : Funai, 1978. 196 p. (Originalmente Tese de Livre Docência na UFRJ, 1968).

- --------. Representações iconográficas do corpo em duas sociedades indígenas : Mehinaku e Karajá. Rev. do Museu de Arqueol. e Etnol., São Paulo : MAE, n. 7, p. 65-9, 1997.

- --------; MALHANO, Hamilton Botelho. A habitação indígena brasileira. In: RIBEIRO, Berta (Coord.). Suma Etnológica Brasileira. v. 2, Tecnologia indígena. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1986. p. 27-94.

- DIETSCHY, Hans. Cultura como sistema psico-higiênico. In: SCHADEN, E. (Org.). Leituras de Etnologia Brasileira, São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 315-22.

- DONAHUE JUNIOR, George R. A contribution to the etnography of the Karaja indians of Central Brazil. Virginia : Univ. Microfilms International, 1982. 348 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- EHRENREICH, Paul. Contribuições para a etnologia do Brasil. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 7-135, 1948.

- FONSECA, José Pinto. Da cópia da carta que o alferes José Pinto da Fonseca escreveu ao Exm. General de Goiás, dando-lhe conta do descobrimento de duas nações de índios, dirigida do sítio onde portou. Rev. do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro : IHGB, v. 8, 1868.

- FORTUNE, David; FORTUNE, Gretchen. Karajá literary acquisition and sociocultural effects on a rapidly changing culture. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, s.l. : s.ed., v. 8, n. 6, 1987.

- FORTUNE, Gretchen, The importance of turtle months in the Karaja world, with a focus on ethnobiology in indigenous literary education. In: POSEY, Darrell A.; OVERAL, William Leslie (Orgs.). Ethnobiology : implications and applications. Proceedings of the First International Congress of Ethnobiology (Belem, 1988). v.1. Belém : MPEG, 1990. p. 89-98.

- FUNDAÇÃO DE AMPARO E DESENVOLVIMENTO DE PESQUISA. Estudos de Impacto Ambiental : Hidrovia Tocantins-Araguaia. v. 1, Texto Principal. Belém : Fadesp, 1999.

- GIANNINI, Isabelle Vidal. Relatório ambiental de identificação e delimitação Terra Indígena Cacique Fontoura. São Paulo : s.ed., 2001. 98 p.

- KRAUSE, Fritz. Nos sertões do Brasil. Rev. do Arquivo Municipal, São Paulo : Arquivo Municipal, v. 66 a v. 91, 1940/1943.

- LEITÃO, Rosani Moreira. Educação e tradição : o significado da educação escolar para o povo Karajá de Santa Isabel do Morro, Ilha do Bananal-TO. Goiânia : UFGO, 1997. 297 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- LIMA FILHO, Manuel Ferreira. Os filhos do Araguaia : reflexões etnográficas sobre o “Hetohoky” Karajá, um rito de iniciação masculina. Brasília : UnB, 1991. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Publicada com o título “Hetohoký : um rito Karajá”. Goiânia : UCG, 1995. 183 p.

- LIPKIND, William. The Carajá. In: STEWARD, J. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v. 3. Washington : Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, 1948.

- MELO, Juliana Gonçalves de. Um estudo sobre o contato interétnico e seu impacto nas crenças e práticas médicas Karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1999. (Monografia de Graduação)

- OLIVEIRA, Haroldo Cândido. Sobre os dentes Karajá de Santa Isabel. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : Museu Paulista, v. 2, n.s., p. 169-74, 1948.

- PAINKOW, Aurielly Queiroz et al. Aldeias da ilha : estudos e registros da realidade social dos indígenas que habitam a Ilha do Bananal. Palmas : Univers. do Tocantins, 2002. 48 p.

- PAULA, Luiz Gouvea de. “Fala direito, Karajá!”. Rev. do Museu Antropológico, Goiânia : UFGO, v. ¾, n. 1, p. 53-64, jan./dez.1999/2000.

- PERET, João Américo. As filhas do sol e a origem do casamento : lenda Karajá. Arquivo de Anat. e Antrop., Rio de Janeiro : Inst. Antrop. Prof. S. Marques, n. 4, p. 457-61, 1980.

- PETESCH, Nathalie. La pirogue de sable modes de représentation et d’organisation d’une société du fleuve : les Karajá de l’Araguaia (Brésil central). Paris : Université Paris X, 1992. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. A trilogia Karajá : sua posição intermediária no continuum Jê-Tupi. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Orgs.). Amazônia : etnologia e história indígena. São Paulo : USP-NHII/Fapesp, 1993. p. 365-84. (Estudos)

- PIMENTEL, Maria do Socorro. A educação na revitalização da língua e da cultura Karajá na aldeia de Buridina. Rev. do Museu Antropológico, Goiânia : UFGO, v. ¾, n. 1, p. 65-74, jan./dez. 1999/2000.

- POLECK, Lydia (Org.). Adornos e pintura corporal Karajá. Goiânia : UFGO ; Brasília : Funai, 1994. 47 p. (Textos Indígenas, Série Cultura)

- --------. Textos Karajá. Goiânia : UFGO, 1998. 51 p. (Textos Indígenas, Série Cultura)

- RAMALHO, Jair Pereira. Pesquisas antropológicas nos índios do Brasil : a cefalometria nos Kayapó e Karajá. Rio de Janeiro : Fed. das Escolas Federais Isoladas, 1971. 314 p. (Tese para Concurso Prof. Titular de Anatomia)

- --------; PAPAIS, Regina Maria. Pesquisas antropométricas em brasilíndios : o diâmetro bizigomático e altura morfológica da face nos Karajá - coeficiente de correlação. Arquivos do Instituto Benjamin Baptista, Rio de Janeiro : Instituto Benjamin Baptista, v. 15, p. 453-9, 1972.

- RAMOS, Luciana Maria de Moura. A construção da mulher na sociedade Karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1996. (Monografia de Graduação)

- RIBEIRO, Eduardo Rivail. (ATR) vowel harmony and palatalization in Karaja. Santa Bárbara Papers in Linguistics, Santa Bárbara : UCSB, v. 10, 2000.

- RODRIGUES, Patrícia de Mendonça. O povo do Meio : tempo, cosmo e gênero entre os Javaé da ilha do Bananal. Brasília : UnB, 1993. 438 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SÁ, Cristina. Observações sobre a habitação em três grupos indígenas brasileiros. In: NOVAES, Sylvia Caiuby (Org.). Habitações indígenas. São Paulo : Nobel ; Edusp, 1983. p. 103-46.

- SANTOS, Rosirene R. dos. A estética Karajá e a ótica ocidental. São Paulo : USP, 2001. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SILVA, Maria do Socorro Pimentel da. A função social do mito na revitalização cultural da língua Karajá. São Paulo : PUC, 2001. 242 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. A situação sociolingüística dos Karajá de Santa Isabel do Morro e Fontoura. Brasília : Funai/Dedoc, 2001. 143 p. Originalmente Dissertação de Mestrado/UFGO.

- SIMÕES, Mário Ferreira. Cerâmica Karajá e outras notas etnográficas. Goiânia : UCG-IGPHA, 1992.

- TAVEIRA, Edna Luisa de Melo. Etnografia da cesta Karaja. São Paulo : USP, 1978. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Publicada com o mesmo título em 1982 pela UFGO.

- TAVENER, Christopher J. The Karajá and the Brazilian frontier. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (Ed.). Peoples and cultures of native South America : an anthropological reader. New York : The American Museum of Natural Story, 1973. p. 433-62.

- TORAL, André Amaral de. Cosmologia e sociedade Karajá. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ-Museu Nacional, 1992. 414 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Estudo de Impacto Ambiental - Hidrovia Araguaia-Tocantins : diagnóstico ambiental Karajá. São Paulo : s.ed., 1997. 127 p.

- --------. Laudo pericial antropológico relativo à Ação Ordinária de nº 91.0004263-3 (I-1.363/91) de desapropriação indireta na 4ª Vara da Justiça Federal do Mato Grosso. s.l. : s.ed., 1992. 120 p.

- TSUPAL, Nancy Antunes. Educação indígena bilingue, particularmente entre Karajá e Xavante : alguns aspectos pedagógicos, considerações e sugestões. Brasília : UnB, 1979. 157 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- VIANA, Adriana M. S. A expressão do atributo na língua karajá. Brasília : UnB, 1995. 89 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- Tigrero : the film that was never made. Dir.: Mika Kaurismaki. Filme Cor, 35 mm, 1994.

VIDEOS