Jarawara

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- AM 271 (Jarawara, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Arawá

The Jarawara are among the little known indigenous peoples of the region of the Juruá and Purus rivers. They speak a language of the Arawá family and inhabit only one indigenous reserve. This entry summarizes the little information that exists about them.

Name and location

Another spelling of the ethnonym is Jarauara. It is not known whether there is another self-denomination, other than Jarawara. Gunter Kroemer, of the Indigenist Missionary Council (Cimi) of Lábrea, classifies them as a subgroup of the Jamamadi, but their language is different, which led the SIL (International Linguistics Society, formerly Summer Institute of Linguistics) to send a missionary to study it, verifying that these people are in no way identified with the Jamamadi.

Location

The present territory of the Jarawara is situated in the region of the middle Purús River and represents about 30% of the Jarawara/Jamamadi/Kanamanti Indigenous Land. This land, homologated and with a surface area of 390,233 hectares, lies in the municipalities of Lábrea and Tapauá, in the State of Amazonas. The territory covers regions of terra firme and the edges of low plateaus, which form an interface between terra firme and the várzea (floodplains). The predominant vegetation is formed by dense ombrophylous forests of the low plateaus and dense ombrophylous forests of the periodically flooded alluvial plains.

Language

The Jarawara language belongs to the small Arawá family of Western Amazônia. The Jarawara informed us that they understand the Jamamadi and Banawa Yafi languages with ease. Few individuals, however, dominate the Portuguese language.

Economic activities

The annual cycle is marked by the rains, more intense in the months of November to February, and by the water levels, which are generally higher in March and April and lower from July to October.

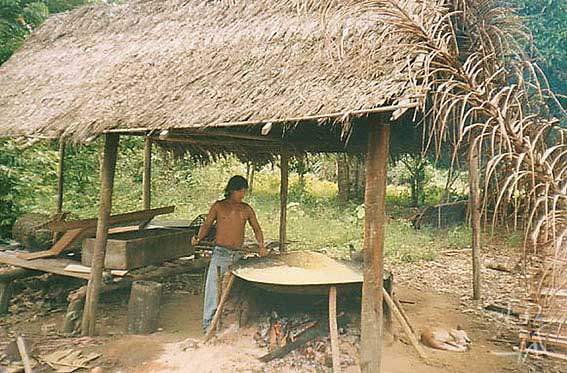

The Jarawara are basically terra firme agriculturalists who supplement their diet with hunting and fishing. In their gardens, they plant mainly manioc, yams, sweet potatoes, ariá, sweet cassava, taro, corn, bananas, pineapple, pumpkin, watermelon, cashew and pupunha, but also sugarcane, tobacco and a vine called kona, from which they produce fish poison, or tingui. They plant at least 17 varieties of manioc and 5 varieties of sweet cassava. In their backyards, called yamabarikani ("near the house"), the Jarawara cultivate more than 30 species of fruit trees, palm trees, legumes, vegetables, condiments, spices and medicinal plants.

The Jarawara hunt not only on terra firme, but also on the small islands found in the floodplains of the Purus and which normally are not submerged during the flood season thus concentrating a series of seasonally hunted species.

For fishing, various kinds of environment are used throughout the whole year. There is evidence that fish represents an important element in the Jarawara diet. Among the diverse techniques utilized, it is worth mentioning fishing with plant poison (kona). Kona appears to be the same species cultivated among the Jamamadi and Zuruahá.

The Jarawara commercialize mainly extractivist products, such as rubber latex, Brazil-nuts, copaíba oil and sorb, while agricultural products and artwork are of secondary importance in commercial trade. The Jarawara have become dependent on various kinds of industrialized merchandise, but they are in a very disadvantageous position for acquiring it and have little familiarity with the value of money. For this reason, the regional population is able to take great advantage of them in their commercial trades.

Social and political organization

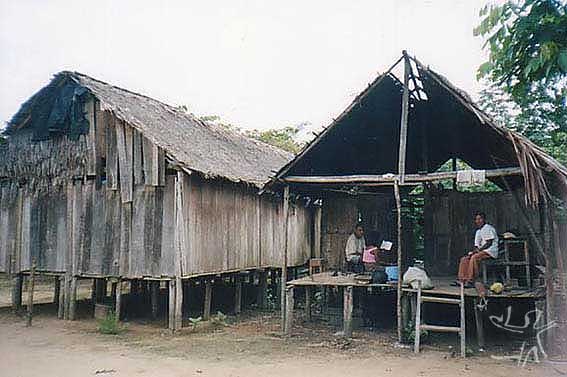

Local groups are very small. In the past, they were formed by the dwellers of a single maloca. The information available indicates that the local groups of the past were large extended families.

Marriage was preferentially between cross-cousins (father’s sister’s children or mother’s brother’s children), although this was practiced more in the past than it is today. Post-marital residence is generally with the wife’s family (uxorilocality), but also can be with the husband’s family (virilocality). After several years, the married couple may opt between virilocality, uxorilocality, or a new residence of their own (neolocality).

The leadership of a local group is assumed by the head of the largest family of the community. There is a term for "leader", botehefo, which is also translated by the Jarawara as "tuxaua". In the past, an important condition for exercising this function was having warrior abilities.

We still do not have information available on other aspects of Jarawara culture, such as religion, shamanism, mythology and arts.

Notes on the sources

There is still no ethnographic monograph about the Jarawara. The language was studied by the missionary Alan Vogel, of the SIL.

Sources of information

- CHANDLESS, W. (1866), “Chandless’s Notes on the River Purús”, The Journal of The Royal Geographical Society, 36. ______________ (1869), “Notes of a journey up the river Jurua”, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 39, p.296-311.

- COUTINHO, J. M. (1862), Relatório da exploração do rio Purús, Rio de Janeiro, Typographia de João Ignacio da Silva, 96 p.

- CUNHA, E.(1986), Um paraíso perdido (ensaios, estudos e pronunciamentos sobre a Amazônia), Rio de Janeiro, José Olympio, Fundação de Desenvolvimento de Recursos Humanos da Cultura e do Desporto do Governo do Estado do Acre.

- DIXON, R. M. W. (1995), “Fusional Development of gender marking in Jarawara”, International Journal of American Linguistics, 61, p. 263-294.

- _______________ (1999), “Arawá”, in R. M. W. Dixon e A. Y. Aikhenvald (eds), The Amazonian Languages, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 292-306.

- _______________ (2000a), “Categories of the noun phrase in Jarawara”. Journal of Linguistics, 36, p. 487-510.

- _______________ (2000b), “A-construction and O-construction in Jarawara”, , International Journal of American Linguistics, 66, p. 22-56.

- _______________ (2001), “International reconstruction of tense-modal suffixes in Jarawara”, Diachronica, 18, p. 3-30.

- _______________ (2002), “The eclectic morphology of Jarawara and the status of word”, in R. M. W. Dixon e A. Y. Aikhenvald (eds), Word: a Cross-Linguistic Typology, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p.125-152.

- _______________ (2003), “Evidentially in Jarawara”, Studies in evidentially, in R. M. W. Dixon e A. Y. Aikhenvald (eds), Amsterdam, John Benjamins, p. 165-187.

- _______________ (2004a), The Jarawara language of southern Amazonia, New York, Oxford University Press.

- _______________ (2004b), “Proto-Arawá phonology”, Anthropological Linguistics, 46, p. 1-83.

- _______________ (2004c), “The small adjective class in Jarawara”, in R. M. W. Dixon e A. Y. Aikhenvald (eds), Adjective classes, a cross-linguistic typology (Explorations in linguistic typology, vol. 1), Oxford, Oxford University press, p. 177-189

- DIXON, R. M. W. e VOGEL, A. R. (1996), “Reduplication in Jarawara”, Languages of the World, 10, p. 24-31.

- EHRENREICH, P. (1929), “Viagem nos rios Amazonas e Purús”, Revista do Museu Paulista, tomo XVI, p. 279-312.

- _______________ (1948), “Contribuições para a etnologia do Brasil”, Revista do Museu Paulista, N.S., II, p.7-35.

- KROEMER, G. (1985), Cuxiuara, o Purus dos indígenas, São Paulo, Loyola.

- MÉTRAUX, A. (1948), “Tribes of the Juruá-Purus basins”, in J. Steward (ed), Handbook of South American Indians, vol III (The Tropical Forest Tribes), Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 143, Washington D. C.

- PRANCE, G. T. (1978), “The poisons and narcotics of the Dení, Paumari, Jamamadi and Jarawara indians of the Purus River region”, Revista Brasileira de Botânica, v. 1, p. 71-82.

- RIVET, P.& TASTEVIN, C. (1921), “Les tribus indiennes des bassin du Purus, du Juruá e des régions limitrophes”, La Géographie, XXXV, nº 5, p. 470-479.

- SCHRÖDER, P. (2002), “Levantamento Etnoecológico do Complexo Médio Purus II - Resumo”, relatório para o Projeto Integrado de Proteção às Populações e Terras Indígenas da Amazônia Legal (PPTAL), mimeo

- STEERE, J. B. (1901), Narrative of a visit to Indian tribes of the Purus River, Brazil, Washington, Smithsonian Institution, Ann Arbor Michigan.

- VENCIO, E. (1996), Cartas entre os Jarawara: um estudo da apropriação da escrita, Dissertação de Mestrado em linguística, Unicamp.

- VOGEL, A. R. (1989), Gender and gender agreement in Jaruára (Arauan), M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Arlington.

- ____________ (2003), Jarawara verb classes, Tese de doutorado em filosofia, University of Pittsburgh.

- ___________ (2006), “Dicionário Jarawara- Português”, Sociedade Internacional de Lingüística, Cuiabá, edição online.

- WILKENS DE MATTOS, J. (1855), “Roteiro da primeira viagem do vapor ‘Monarca’ em 1854”, relatório do 11de março de 1855, Ministério da Agricultura, vol. I.