Ikolen

- Self-denomination

- Digut

- Where they are How many

- RO 691 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Mondé

The Ikolen, also known as the Gavião, speak a language of the Tupi-Mondé family. They live in the basin of the Lourdes river, a tributary of the Machado (or Ji-Paraná) river, in the state of Rondônia near the border with the state of Mato Grosso. Their population is divided among six villages, all located within the Terra Indígena (TI) Igarapé Lourdes, which they share with another indigenous group, the Karo.

Name

The group refers to itself as Ikolen, which in their language means ‘hawk’ (or ‘gavião’ in Portuguese). For this reason the Ikolen are referred to as the Gavião or the Gavião de Rondônia, a way of distinguishing them from other indigenous groups also known as Gavião, such as the: Gavião Parkatêjê (in the state of Pará) and the Gavião Pykopjê (in the state of Maranhão).

Another less common name is Digüt or Digut, which arose from a misunderstanding on the part of the anthropologist Harold Schultz who wrongly understood the personal name of an indigenous interlocutor as the being the collective name for the Ikolen as a whole.

Language

The Ikolen are speakers of a language from the Mondé (Tupi-Mondé) branch of the Tupi language family, which is genetically related to the languages spoken by their allies the Zoró and their old enemies the Paiter and the Cinta-Larga.

Location

The Ikolen inhabit a region of the basin of the Lourdes and other tributaries of the Machado (or Ji-Paraná) in the eastern part of the state of Rondônia, on the border with the state of Mato Grosso. Until the beginning of the 1940s, the Ikolen occupied part of the headwaters of the Branco river, in the Aripuanã basin. In this region they enjoyed a close relationship, including intermarriage, with the Zoró, and were thus frequently confused with these. After suffering attacks from the Paiter and Cinta Larga groups and the hostilities of non-indigenous farmers, the Ikolen moved to their current location, occupying the headwaters of the Lourdes, in the Serra da Providência.

Nowadays the Ikolen population is divided among six villages: Igarapé Lourdes, Ikolen, Cacoal, Nova Esperança, Castanheira and Ingazeira. All of these are located within the Terra Indígena Igarapé Lourdes, around 60 kilometres from the town of Jí-Paraná.

The TI Igarapé Lourdes was demarcated in 1976-77 and legally registered in 1983 with a total area of 185,533 hectares. The boundaries of the reserve are the Machado to the west, the border with the state of Mato Grosso to the east, the Prainha river and a land transect to the south and finally the Água Azul river to the north (where the reserve overlies the Jaru Biological Reserve).

The largest part of this area is covered by open or closed tropical forest, with areas of grassland in the region near the Serra da Providência. A dense network of streams occurs within the TI Igarapé Lourdes forming seasonally flooded plains and dense gallery forest.

Population

The current Ikolen population is more than 520 people distributed among the six villages of the TI Igarapé Lourdes.

There are no reliable demographic data prior to or contemporaneous with their first contact with non-indigenous people. The first available references to Ikolen demographics were collected from 1975 onwards. For this reason it is difficult to estimate demographic trends.

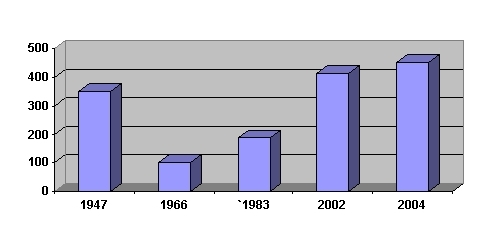

According to reports, in 1946-47 the Ikolen population numbered about 300 people. However, this information is not reliable given the frequent confusion of the Ikolen with the Zoró and the Karo. During the 1960s, when the first contacts with missionaries and the SPI (the former federal Indian Protection Service) took place, the Ikolen numbered fewer than 100 people. Since then, the population has grown thanks to the assistance provided by FUNAI (the current federal National Indian Foundation) and the missionaries.

By 1983 they totalled 220 people, distributed among eighteen sub-villages or "colocações".

[Graph 1: Population history of the Ikolen / Ikolen people / Source: Reports by Denny Moore, Funai 2002 and Funasa 200]

Because of the high mortality rate during early contact with non-indigenous people and the recent demographic growth, the current Ikolen population is made up mainly of young people. For example, around 40% of the population is aged 10 or less and those below 20 make up 60% of the population. On the other hand, the number of elders is extremely low. In 2004 there were only eight people aged 66 or over. It is precisely these elders who hold the knowledge of important aspects of Ikolen culture, such as music, myths, rites, language and material culture.

Graph 2: Population distribution by age range and gender (Source: Funasa Ji-Paraná, 2004)

History of contact with non-indigenous people

Little is known about the history of contact between the Ikolen and non-indians. As with many other indigenous groups, the Ikolen suffered the impacts of the expansion of the economic frontier onto their lands: in the 1940s the second rubber boom, and after 1970 logging, incoming settlers and farming.

In all these relationships, whether with non-indians or with other indigenous groups, periods of peace, interethnic marriages and insertion into the regional economy alternated with moments of tension and conflicts that mostly ended in bloodshed, episodes still remembered by the older Ikolen. This was a period marked by high mortality levels, with flu, pneumonia, measles and malaria epidemics caused by contact with the outsiders.

The first contacts between the Ikolen and the outside world took place in the 1940s and were mediated by the Karo, who were in contact with rubber tappers on the banks of the Machado (Jí-Parana) river.

In the 1950s, as a consequence of the growth of rubber tapping and the beginning of mining in the region, there were a large number of deaths among the Ikolen. From 1953 onwards the Ikolen became permanently close to non-indians, periodically working as rubber tappers in exchange for clothes and tools. The presence of non-indigenous people significantly altered the relations between the Ikolen and the Karo, who begun to compete with each other for the new resources introduced, above all manufactured goods.

In 1965, the Ikolen established contact with missionaries from the New Tribes Mission of Brazil, who had begun their work of evangelising the residents of the TI Igarapé Lourdes. The following year, the Indian Protection Service (SPI) arrived in the region, beginning a process of resettling and re-approximating the Ikolen and the Karo who were now scattered throughout the area of rubber collecting. This was the first step towards the creation of the TI Igarapé Lourdes.

Land Situation

The Terra Indígena Igarapé Lourdes was demarcated in 1976-77 and registered in 1983, but it did not cover the complete territory traditionally occupied by the Ikolen. As a result, former Ikolen villages on the Branco and some of its tributaries were left out of the area demarcated. In addition, this process of regularizing their territory was not enough to protect the area from the frontier expansion front that intensified in the region after the construction of the BR-364 highway in the municipality of Jí-Parana in the mid-1970s.

Up to then, the only way to get into the region had been by river; departing from Manaus and travelling as far as the meeting of the Madeira and Machado rivers. Because of the many rapids and obstacles, navigation along the Machado made it difficult for the expanding frontier to reach the area inhabited by the Ikolen, leaving it relatively isolated.

With the highway, the territory inhabited by the Ikolen became attractive to farmers, ranchers, and loggers, as well as becoming the destination of settlers from Brazil’s centre-south region, encouraged by the federal government’s National Integration Programme (PIN). As a consequence of heavy political and economic pressure, the original boundaries of the TI Igarapé Lourdes Indigenous Reserve were altered, thereby reducing and dismembering the area, to the disadvantage of the Ikolen and the other inhabitants of the reserve. In 1975, the building of a road into the demarcated area prompted its invasion by settlers. Several ranches were opened in the area between the TI Igarapé Lourdes and the Aripuanã Indigenous Park, home to other Tupi-Mondé groups (the Paiter, Zoró and Cinta Larga) with whom the Ikolen maintained relationships.

The reaction of the Ikolen and Karo led to the establishment of road tolls and other forms of compensation for the indigenous groups affected by the roads; however the problem continues unresolved. In the 1980s, the Northwest Integrated Development Programme (Polonoroeste), financed by the Brazilian government and the World Bank encouraged the process of non-indigenous occupation, thus worsening the conflict. Various feeder roads and illegal homesteads along the road were opened up by the loggers, further stimulating the wave of illegal occupation of the TI Igarapé Lourdes.

Faced with the growing invasion of their territory, the Ikolen and Karo joined forces against the projects underway. This led to the suspension of project funding by the World Bank pending more robust indigenous peoples’ and environmental protection measures.

In between 1991 and 2001, the World Bank financed the Rôndonia Natural Resource Management Project (Planafloro) which aimed to correct the distortions produced by the previous programme (Polonoroeste). The Planafloro foresaw a series of actions geared towards health and education provision for indigenous people; the demarcation, policing and protection of indigenous lands; and development programmes centred on these communities.

Despite the progress achieved in the last few years, the Ikolen and the other inhabitants of the TI Igarapé Lourdes continue to fight for the revision of the eastern boundary of their territory, so as to incorporate the former Ikolen area in the Serra da Providencia. In addition they are demanding a solution to the problem of the road that crosses the reserve on its north-eastern boundary; as well as the incorporation of two tributaries of the Água Azul that currently form part of the Jaru Biological Reserve to the north.

Relationships with other indigenous people

The Ikolen have had longstanding close relationships with the Karo and Zoró. Intermarriages date from the beginning of the twentieth century, as a consequence of the warrior custom of kidnapping and incorporating enemy women and children into the group. Until the beginning of the 1940s, the Ikolen inhabited a number of tributaries of the Branco in the Aripuanã basin, a region where they had close relationships of cohabitation and intermarriage with the Zoró, with whom they were frequently confused. After being attacked by the Paiter and Cinta Larga and suffering the hostilities of the ranchers, the Ikolen and the Zoró migrated southeast towards the Serra da Providência, mainly around the headwaters of the Lourdes, Prainha and Tarumá rivers and other tributaries of the Machado (Jí-Parana). These rivers were already inhabited by the Karo.

Even though they spoke different languages, the Ikolen had been in contact with the Karo on the lower Lourdes even before contact with outsiders. They had co-existed in the region for decades, always reserving some areas for the exclusive use of each. The Ikolen were predominant on the headwaters and upper rivers, whereas the Karo kept to the lower reaches.

However, the relationship between the Ikolen and the Karo changed significantly when they were forced to compete for the resources arriving from the outside world as a result of their contacts with rubber tappers and other intermediaries. Now subject to the pressures and dynamics of the expanding frontier, the relationship between the two groups was characterized both by cultural exchanges, intermarriage and alliances as well as by conflicts and deaths. The last conflict happened in 1959, when the Ikolen surrounded four Karo villages, killing seven people and kidnapping a number of women.

In the same way, despite their proximity, their intermarriages and the fact that they spoke the same language, the Ikolen and the Zoró grew apart following a conflict in the period 1946-47. They remained apart for decades until 1977, when once again threatened by the Paiter and Cinta-Larga, as well as by the ranchers in the region, the Zoró sought to rekindle their relationship with the Ikolen. Soon after contact with FUNAI in 1978, the majority of the Zoró remained living in the main Ikolen village on the Lourdes. There were celebrations and marriages during this brief period, but the following year, fleeing illness, the majority of the Zoró returned back to the Branco river in the Aripuanã valley, where they their territory would later be regularized.

Nowadays, the relationship between the Ikolen and other indigenous groups is characterized by new ways of collaboration and organization, such as the creation of the Organization of Associations of Indigenous Peoples of Jí-Parana (Panderej).

Social Organization

Intermarriage between the Ikolen and the Zoró or the Karo is very frequent. In such cases the Ikolen usually say that the children belong to the father’s group. However in practice there are so many exceptions to this rule that it is obvious that a lot of other factors come into play.

First we need to remember that these groups are not patrilinear, but bilateral. In other words they consider as relatives both the relatives of the mother as well as those of the father. Second the residency rules must be looked at. It is customary among all these groups that the new couple spend the early years of the marriage living with the wife’s family. The initial rule is thus one of matrilocal residence. But after this period, the couple have the freedom to go and live wherever they choose. Thus the choice depends on several factors: the number of close relatives the husband and the wife each have; whether they like the people where they are living; whether they can play an influential role within the local group; and so on. Often however the couple ends up moving to the place where the husband’s group lives.

In the long run therefore the choice of residence tends to be patrilocal, but there are many couples that carry on living with the wife’s group. The Ikolen and the other groups are very flexible and, in practice, a child ends up belonging to the group where it grows up without losing its connections to the other group.

Ritual Practices

Following contact and deteriorating relations with non-indians, various factors have inhibited Ikolen cultural self-esteem. Amongst these are the drastic loss of the older generation, holders of the knowledge of the traditions; discrimination by non-indians; neglect and omission on the part of the SPI and FUNAI; and above all, proselytizing by missionaries.

The missionaries from the New Tribes Mission of Brazil first made contact with the Ikolen in 1965. Two years later, they took up residence in the TI Igarapé Lourdes and co-opted the most influential Ikolen leaders into taking part in their catechism activities. In addition to their linguistic work and the preparation of teaching materials, the missionaries introduced concepts and values that went against Ikolen culture, resulting in many Ikolen abandoning their ritual practices.

Although the FUNAI resident agent had in the 1970s forbidden the Ikolen from holding their rituals, fearing that these would affect their health and population growth, the ceremonies and shamanistic activities were nevertheless revived during that same period.

However, the decisive moment for the Ikolen reclaiming their cultural heritage was the reappearance of a shaman at the beginning of the 1980s. Although converted and baptized by the missionaries, he escaped from the ‘Casa do Indio’ in Porto Velho, abandoning the medical treatment he was receiving. After being taken for dead, he re-appeared four months later in the TI Igarapé Lourdes, where he recounted his experiences of initiation into magic. From this moment on, there was a revival of traditional practices (above all shamanism), as well as the start of a syncretic movement combining western religion and traditional Ikolen knowledge and practices.

In short, despite the presence of the missionaries and the pressures of the surrounding society, traditional Ikolen practices, shamanism and knowledge persist and are acquiring increasing importance in their lives. The Ikolen nowadays hold many ceremonies at different times of the year, the majority relating to harvesting their crops. There are also rituals for healing by shamans and the ‘meeting of the shamans’, which each August brings together representatives of all the Ikolen and Karo villages.

As a result of their contact with non-indians other festivities have been adopted, such as the celebrations of Christmas and New Year, as well as birthdays and the national celebrations in June commemorating St. John’s Day. In April the Day of the Indian is commemorated and in August there are the Indigenous Games involving sporting competitions, festivities and dancing.

Cosmology

To the Ikolen, nature with its myriad forms of animal and plant life is the concrete result of a series of creative acts carried out by an individual - half-man, half-god - who lived here on earth at the beginning of time. The Ikolen call this individual Gora’ and possess a rich mythological tradition that relates the details of the events that resulted in the creation of the world as we known.

Through these mythic tales, the Ikolen learn the circumstances which gave each species their distinctive characteristics: the monkey and its tail; parrots and their rounded beaks; toucans and their long beaks; the Brazil nut tree and its great height; the assai palm with its dark fruits, and so on. Thus every life form has its own characteristics resulting from an act by Gora' and thus forever contains within itself the ‘mark of the creator’. Each form is the living memory of a creative act at the beginning of time.

Thus, nature itself - in its details and overall - is imbued with religious significance. But it is not only its origins that give nature its spiritual side. To the Ikolen, in addition to their material forms, all life forms also have a spiritual side, which is no less real. Each animal has its own spirit, its spiritual body (one could say its soul), which stays with the body whilst it is alive and carries on living when the animal dies. As Ikolen say, these spirits are ‘wise’ and the shamans know how to communicate with them - at least with the ‘wisest’, such as the spirits of the tapir, wild boar, jaguar and monkey.

But it is not only animals that have this spiritual side. Each tree has its spirit and there is a large group of spirits that are the ‘owners of the fruits’.

With the indiscriminate destruction of the forest around (and inside) the TI Igarapé Lourdes, many tree spirits have suddenly been deprived of their homes and condemned to roam - in vain - in search of new abodes. Only the shaman has the sensibility to perceive this invisible drama and the problems – for which he is not to blame - fall on his shoulders.

Even though this may seem too exotic, it helps uncover the Ikolen view of the world. It is not that an Ikolen is scared or has to ask permission every time he has to chop down a tree to build a house. The felling of one or more trees is an interference with the limits of nature itself. The wind can bring down trees, one tree can die strangled by another stronger tree, other ones will be born in their place - none of those things are contrary to the laws of nature.

The same happens with animals. The hunter is free to hunt, but must need what he kills. In the only type of hunting where wastage and over-hunting can occur - the collective hunt for wild peccary - the shaman plays the role of moderator, able to call for the hunt to stop.

What is important is not the question of whether or not there is interference with nature (of which human beings are also a part). What matters to the Ikolen is the level of that interference. Killing peccary is allowed, but not to the point of putting the survival of the species at risk. If exaggerated, this would be to provoke the spirits of the peccary, to provoke the spiritual owner of the peccaries (since they believe that all peccary herds have such a spiritual owner) and would be an offence towards the Gora’, who created the peccary to remain in the forest.

Any widespread interference capable of altering the chances of survival of animal and plant species – exterminating some for the benefit of others – will thus have, in addition to its socioeconomic and environmental impacts, a profound religious significance as well. It would cause chaos at a spiritual level – something also dangerous for humans – and would offend the order established by Gora’.

Abode of the spirits

To the Ikolen, each river or stream - or any stretch of one - has its spiritual owners. These are the Gonjan-ei, groups of spirits that live in villages below the waters, who are the owners of the fish and the regulators of rain, tempests and thunder.

They are a very important group - and also very feared - within the Ikolen universe. They are well known for being able to steal souls and take them to underground villages, causing illness and death if the shaman is unable to find out the cause of the illness and rescue the soul before it is too late.

The Ikolen avoid any behaviour that could provoke the Gonjan-ei and at the most important festivity of the year, the festival of the new corn, the Gonjan-ei are always the guests of honour. No one is allowed to taste the fresh corn before it has been offered to the leader of the Gonjan-ei. Whoever breaks this rule will be held responsible for any climatic disturbances and tempests (the vengeance of the Gonjan-ei) that may destroy the harvests of the following year.

The Gonjan-ei are therefore a group of spirits considered ambivalent. They are powerful and can be dangerous, but are not considered malevolent in nature. The shaman maintains good relationships with them, frequently visiting and in exchange inviting them to ceremonies. As long as certain precautions are taken, they will not generally harm the Ikolen – except by causing illnesses. These are always attributed to the activity of a single Gonjan and not to the group as a whole.

However, the Ikolen say that a radical change in the aquatic environment would dramatically provoke the Gonjan-ei as a group for two reasons. First, because it would kill a lot of fish – and the fish belong to the Gonjan-ei, being animals domesticated by them; and second, because it would alter the prevailing organization of the aquatic world, causing chaos.

Subsistence activities

The Ikolen engage in a diverse set of subsistence activities, such as hunting, fishing, swidden agriculture, animal husbandry and agroforestry systems aimed both at internal consumption and income generation. On the whole, all members of the community, regardless of sex or age, carry out these activities in a communal and family-based way. Family activities are mainly directed towards the subsistence of each family and to the production of small surpluses for barter or sale. In the case of communal activities, all the members of the communities take part and have equal rights over whatever is produced.

Agriculture for consumption and sale

The Ikolen create their gardens near the villages, clearing and then burning the forest and secondary growth, making bonfires of any unburned vegetation if needed. Clearing the area of forest takes place between May and July, sometimes extending until September in the case of areas of secondary growth. The work of clearing the site for the garden falls exclusively to the men, whereas the planting, weeding and harvesting is done by all: men, women and children. Each plot is used on average for three consecutive years. Afterwards it is abandoned for such time until new secondary growth has formed, at which point it can be re-used. With the exception of the main Ikolen village, where there are agricultural implements, all the other villages use manual planting and management.

In their gardens the Ikolen cultivate a large variety of sweet and bitter manioc, sweet potatoes, yams, aroids and taro, which are eaten boiled, roasted, as sweet or fermented (makaloba) gruel or porridge or used to make manioc meal (farinha) for their own consumption or for sale. Some of these and other crops were introduced by non-indians and have undergone successful adaptations to the Ikolen diet and production methods. This is the case with some varieties of corn, beans and rice produced both for internal consumption and to generate a surplus for sale.

In the gardens and central areas of the villages the Ikolen also grow cotton, used for making rope; annatto, used as a body paint, spice and insect repellent; peanuts; broad beans; sugarcane, papaya, coconut, watermelon, pineapple, pumpkin and different species of banana; oranges, limes and tangerines. All are all grown exclusively for internal consumption.

The range of produce that generate a surplus for sale is small and the local market has little capacity to absorb the surpluses generated. Such produce is sold in the market in Jí-Parana and represents an important source of income for the Ikolen. Further than this, given the lack of control over agricultural production and the fact that its marketing takes place in a dispersed way, it is difficult to estimate total quantities produced.

Hunting and fishing

The Ikolen hunt and fish only for their own immediate consumption and there is no storage, sale or waste. Hunting is basically a male activity, in which women only participate in exceptional circumstances. A great variety of animals is hunted, from birds to large mammals. The hunters work either alone or in groups, on trails near the villages or at distant watering places preferred by the game. Hunting techniques are passed on from father to son and basically consist of hides (where the camouflaged hunter waits for the prey), imitating animal sounds in order to attract the prey, tracking, the use of a bow and different types of arrows (some of which are dipped in anti-coagulation agents that cause the prey to haemorrhage), and lastly, shotguns of various calibres that have come to replace the bow and arrow.

In its turn, fishing is an activity carried out by both men and women. In the rainy season, there is fish in abundance, especially in the Parainha and Lourdes. During the dry season, when rivers have lower volumes of water and these two streams almost dry up, the Ikolen go fishing in the Machado, where there is an abundance of fish. Fishing is carried out with a bow and arrows with peach palm wood, jaguar bone or metal tips. The use of the ‘timbó’ vine is also frequent during the dry season. Other tools used in fishing are harpoons and spears, rods, hooks and lines and nets of various sizes.

Gathering and collecting

In the forests and areas surrounding the villages, the Ikolen collect not only species used in their traditional medicine, but also honey and wild fruits (patoá and babaçu amongst others) for their own consumption.

Animal husbandry

With the help of FUNAI and the Rondônia state government, the Ikolen have devoted themselves to raising cattle and pigs on a family and above all community scale.

Cattle raising is confined to the villages of Ikolen and Igarapé Lourdes. But given the lack of technical expertise, cattle raising has caused a series of problems for the communities. Since there is no proper management of the area destined for the cattle, these get into the vegetable gardens and eat the crops.

A semi intensive fish breeding programme has recently been started in the Ikolen village with the introduction of tilapia and tambaqui fry.

Art and handicrafts

Ikolen material culture is very varied and following contact with the outside world handicrafts began to be produced for sale as well. Women produce the majority of handicrafts, although men also produce feather items with great skill, using parrot, macaw and harpy eagle feathers. Necklaces, bracelets, earrings, rings are also made from palm nuts and animal bones. Basketry, nets and hammocks are made with vegetable fibres, babassu straw, cotton thread and vines, and are used in everyday life, for example for carrying produce.

The volume of handicrafts produced for sale depends in the level of demand in the consumer market. For example, when there are agricultural shows in the surrounding municipalities, production is intensified and almost all of the community is called upon to help. In contrast, when the shows are over, production drops significantly.

Notes on sources

Current knowledge about the Ikolen is still very limited. There is little bibliographical or documental information about them in official archives. Such records as exist date from after their first contact with non-indians (the 1940s).

Even though he referred to the Karo (Arara) and Urumi (Babekawei) of the Machado basin, the ethnographer Curt Nimuendaju made no reference to the Ikolen and the other Tupi-Mondé groups of the region, such as the Cinta-Larga (first contacted in 1968), the Suruí (1969) and the Zoró (1978).

The earliest existing reference to the Ikolen, then called the Gavião and/or the Digüt, was made by Harald Schultz in 1955. It is the first available information about a group of Tupi-Mondé speakers, even though the Ikolen say that they established contact with the Rondon expedition in the early years of the twentieth century.

In 1975, the linguists Denny Moore and Nilson Gabbas Júnior began a study of the Tupi-Mondé languages in the region, among these the language spoken by the Ikolen. Some references to the Ikolen were circulated in technical reports by Mauro Leonel (1983-84) and the research of Lars Lovold in the mid-1980s. The Ikolen only finally appeared in the specialist bibliography with the publication of a study by the anthropologist Betty Mindlin in 2001.

Sources of information

- KANINDÉ, ASSOCIAÇÃO DE DEFESA ETNOAMBIENTAL, Diagnóstico Etnoambiental e Participativo e Plano de Gestão da Terra Indígena Igarapé Lourdes. Rondônia, 2006.

- LOVOLD, Lars & FORSETH, Elisabeth. Estudos de Viabilidade da Usina Hidro-Elétrica de Ji-Paraná. Diagnóstico da Área Indígena Igarapé Lourdes: Uso do Território, Conseqüências do Empreendimento e Recomendações. (Relatório),1988.

- --------.. Through mythical eyes: the traditional world view of the Gavião and the Zoró Indians of Brazil. Institute of Social Anthropology, Oslo. International Peace Research Institute, Oslo.

- LEONEL JÚNIOR, Mauro de Mello. Relatório de avaliação da situação dos Gavião (Digüt) – P.I. Lourdes. São Paulo: FIPE/USP, 1983.

- --------. Relatório complementar de avaliação das invasões no Posto Indígena Lourdes (PIL), dos índios Gavião e Arara (Karo). São Paulo: FIPE/USP, 1984.

- MINDLIN, Betty. Couro dos Espíritos. São Paulo: Editora SENAC/ Terceiro Nome, 2001.

- MOORE, Denny. Relatório sobre o Posto Indígena Lourdes da Oitava Delegacia Regional, segundo diretrizes de levantamentos de dos para elaboração de projetos. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília – UnB, 1978.

- --------. Relatório de pesquisa de campo na Reserva dos Índios Gavião e Arara em Rondônia: Maio e junho de 1987. Belém: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi – MPEG., 1987.

- --------. “Classificação interna da família lingüística Monde”. In: Estudos Lingüísticos XXXIV, p. 515-520, 2005.

- SAMPAIO, Wany; SILVA, Vera da. Os povos indígenas de Rondônia: contribuições para a compreensão de sua cultura e de sua história. Porto Velho: Editora UNIR. 1997, pp. 39-42