Galibi do Oiapoque

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- AP 89 (Siasi/Sesai, 2017)

- Guiana Francesa 3000 (OkaMag, 2002)

- Suriname 3000 (OkaMag, 2002)

- Venezuela 33824 (XIV Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Viviendas, 2011)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

Even though they come from Maná, in French Guiana, the Galibi Indians are considered Brazilians. It is the nationality that they declare and they say that they never want to leave the lands they occupy on the Oiapoque. In the 1950s and 60s, on several occasions, the French authorities tried to convince them to return to Guiana, but they never accepted the proposal. The history of the migration of this group to Brazil, following misunderstandings with affinal kin in their original village, is a quite peculiar saga. They were well-received, upon arrival, by the Brazilian authorities, and always had the support of the SPI employees, like Eurico Fernandes, the first Inspector of this agency in the region, and the anthropologist Expedito Arnaud, and also the friendship of the military in Clevelândia do Norte. For these reasons, their lands were quickly homologated.

Name

Actually, Galibi is the self-designation for a group which lives on the Oiapoque River and for the Indians of the same group who live in French Guiana, especially on the Maroni and Mana rivers. In French Guiana, they call themselves Kaliña, the term Galibi being a generic designation used by the Europeans to refer to the people who speak Carib living along the coast of the Guianas.

Language

The Galibi partially maintain their original language, of which they are quite proud. Many children, however, of Galibi and non-Galibi parents, and who study only Portuguese in the schools, do not speak the Galibi language any longer, even though they understand it.

Many also speak patuá, the criollo language used in contact with other ethnic groups of the region. They speak Portuguese and use patuá in the village and in contacts outside the village. At least the elders know French since they were alphabetized and educated in this language. They undertand a little of Dutch patuá.

These days, the indigenous language is in process of being reaffirmed. Compared to the Karipuna and Galibi-Marworno, the Galibi consider themselves to be true Indians, like the Palikur, because they speak an indigenous language. They question the fact that patuá is considered a "native" language by the Indians of the Uaça, recalling that, in the school of the nuns of Saint Joseph de Cluny, in French Guiana, whoever spoke patuá was punished. There, only the indigenous languages and French were permitted.

Location

The only Galibi village of the Oiapoque, São José dos Galibi, is in the same place where it was built in 1950, when the group arrived in the area. It is located on the right bank of the Oiapoque River, a short distance below the city of Saint Georges, between the Morcego and Taparabu streams. By motorboat, the trip between Oiapoque and the village takes more or less 30 minutes. The village is located on a piece of terra firme land surrounded by family gardens and forest. It occupies an area of approximately 250 by 400 meters, forested and well-kept, where there are houses, orchards and the FUNAI post, infirmary, and school.

Demography

The total population of the Galibi in the village of São José is 28 people. Many live outside the village, in various cities of Amapá, Belém and Brasília. In the village, two couples do not have children and even the schoolteacher, a young man from Vigia, Pará, who is married to a Galibi woman with whom he has five children, will be obliged to move from the area on the day that there are no more students from first to fourth grade.

Migration to the Oiapoque

The Galibi of the Oiapoque come from villages of the Mana River, in French Guiana, Couachi and Grand Village. Their leader, Mr. Geraldo Lod, was born in Pointe Isère. In 1948, Mr. Lod and his cousin succeeded in getting to Belém, where the administrator of the SPI (Serviço de Proteção aos Índios, Indian Protection Service), Eurico Fernandes, gave them authorization and the legal documents so that they could migrate to Brazil with their kingroup. The reason for their migrating wasn’t war, nor hunger, nor pressure from the Whites, but rather a serious and mysterious misunderstanding between affinal kin. On arriving in Brazil, in three sailing canoes, the group consisted of 38 people. Later, several families returned to Mana. Today, with more and more young people leaving the village, the tendency is for population decrease unless non-Galibi individuals or families come to settle in the village. After the death of its eldest members, the group maintained few contacts with the Galibi of French Guiana. Nevertheless, they like to get news from there, especially from kin and friends, often transmitted by a radio program in Caienne.

The village of São José dos Galibi is also the headquarters of the Galibi Indian Post. Geraldo Lod maintains an attitude of autonomy, but a good relationship, with Funai. He chooses and evaluates the employees of the village who, today, are only the head of the post and the teacher, married to a Galibi woman. Mr. Lod, his children and other inhabitants of the village regularly participate in all the Assemblies of Indigenous Peoples of the Uaçá and collective movements to demand their rights, as do other representatives of their and other indigenous peoples who share the same territory, have the same problems and anxieties. It is on these occasions that each group defines its position. They seek to form a consensus and establish a political, economic, and social program that will benefit all. They also participate, along with the Karipuna, Galibi-Marworno and Palikur, in political movements in defense of their rights that are important to them.

While everyone in the village has a good level of education, Mr. Lod stands out for his intellectual capacity and curiosity and discipline in reasoning. His knowledge of the fauna and flora of the Guianas region are surprising. He completed the Certificat d'Études, which corresponds to our primary school education, and for ten years he was a trained nurse in the penitentiary hospital of Saint Laurent, working in indigenous villages of Mana.

His youngest son was president of the APIO (Associação dos Povos Indígenas do Oiapoque, Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the Oiapoque). His two eldest sons are with the military, with very successful careers in the Navy and the Air Force. His four daughters have lived for several years with families of officials from Clevelândia, travelling with them to Belém, Brasília and São Paulo, studying and working, before going back to the Oiapoque. Today, they live in Oiapoque, where they work as employees of the State, and spend their weekends and holidays in the village.

Actually, unlike in the past, the Galibi have little contact with the military of Clevelândia or with people from Saint Georges or Tampac.

Land situation

The lands occupied by the Galibi basically correspond to the territory where they were located in 1950. Having been demarcated, they constitute the Galibi Indian Land (reserve) with a surface area of 6,689 hectares, according to governmental decree no. 1.369/E, of August 2, 1962. The administrative homologation and publication of its confirmation in the Diário Oficial (official press) dates from November 22, 1982. Ariramba, a Karipuna village on the Oiapoque River, was also included in the Galibi reserve and is located in the proximities of the town of Taparabu. Their relations with the Galibi is one of good neighborliness, but little contact.

Cosmology

Religious beliefs are manifest in different ways among different groups of the Uaçá River basin. Among the Karipuna and Galibi-Marworno, popular Catholicism is prevalent, along with a progressivist and activist line, due to the influence of the Indigenist Missionary Council (Cimi), at least until recently. The Catholicism of the Galibi, which for centuries has been incorporated to their beliefs and practices, is of the so-called traditional line.

Shamanism remained alive until the 1960s, and Galibi pajés were well-known and recognized among all the indigenous peoples of Amapá, as were their neighbors, on the other side of the Oiapoque, the Saramaká Blacks of Tampac. Actually, however, there are no more pajés in the group. The symbols of the last pïyei (pajé), the pakará (basketry) and the maracá (rattle), are duly kept by the Galibi. However, the beliefs related to the shamanistic universe have not died out. More than once, the Galibi declared that, compared with those of other groups, their shamans were "true" and competent. Mr. Lod described in minute detail the rituals of initiation, the curing sessions and contact with the spirits. The spirits are divided into two categories, those from on high, the sky, the guardian angels, always good, and the spirits of the forest and water, which are dangerous, and with whom it is necessary to negotiate. On these occasions, it is the spirit of the shaman, who is prepared for this task, who acts, and never the shaman himself, who is just a common man. For the Galibi, God made everything, knows everything and dominates everything, while the shaman, however good he may be, has only a partial vision of the world, and his path may at any time be “closed” by another more powerful shaman. "First comes God, then the maráca".

Long ago, the Galibi say, the spirits of men and animals, who were people in their world, communicated with each other. But now they no longer do so. According to Mr. Lod, at some moment, “something happened”, there was a rupture and today they no longer communicate with each other. This happened because of the incomprehension of the European colonizers in relation to the wisdom of the Indians. A loss and a pity, according to him.

Nevertheless, the Galibi continue to believe that everything in nature has an owner, the animals and the plants. For that reason, they act with special care in their predatory activities of hunting, fishing, and the felling of trees. Or, as they say in French, "one should not make the mistake of annoying them", a delicate way of characterizing the negotiations that link the different domains of the cosmos.

Festivals

The calendar of Galibi festivals also does not correspond to that of the Karipuna or Galibi-Marworno. They do not celebrate the Divine Holy Spirit, as do the Karipuna, and they never were adept at the indigenous Turé rituals, which, according to them, are rituals of the peoples of the forest (de la brousse, of the bush) and not of the peoples of the coast (de la côte). In the past, the great festivals were funerary rituals or rituals that marked the end of mourning and that brought together many of the local groups, in which women’s songs and drum-beaters were important features.

Today, the major festival is celebrated on the last day of the year, when those who live outside the village return to visit their kin and when friends from other places join the Galibi in feasting, eating, dancing and drinking caxixi, fermented manioc drink. The other festivals occur in August, that of Holy Mary which was the great festival in Maná, and São José, the patron saint of the village.

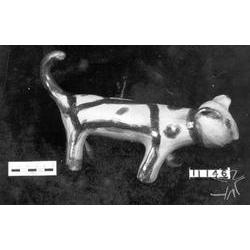

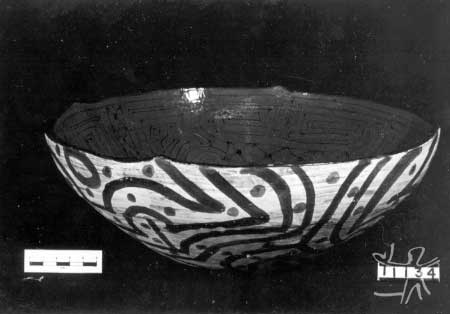

Material Culture

The eldest members of the group, such as Geraldo Lod’s father, a great shaman, and his mother, ceramic artist and accomplished weaver, died a long time ago. Today, without Madame Caroline, Mr. Lod’s wife, only one woman still weaves cotton and knows how to weave the great white hammocks, typical of the Galibi.

The numerous and elaborate artifacts are no longer reproduced and are even less used. "What for?" Mr. Jean-Jaque asks. "There is no-one left". And really, what for ? if the world of today and that of before are totally distinct.

The Galibi, for sure are not “make-believe” Indians. On the other hand, to make artwork in order to sell is something they never contemplated. The objects which they need for subsistence activities, such as sieves, manioc-squeezers, baskets, manioc bread turners, and fans, they continue to make and even a beautiful spindle to spin cotton. But, the painted gourds and manioc scrapers, they obtain on request from the Karipuna of the Curipi River.

Subsistence

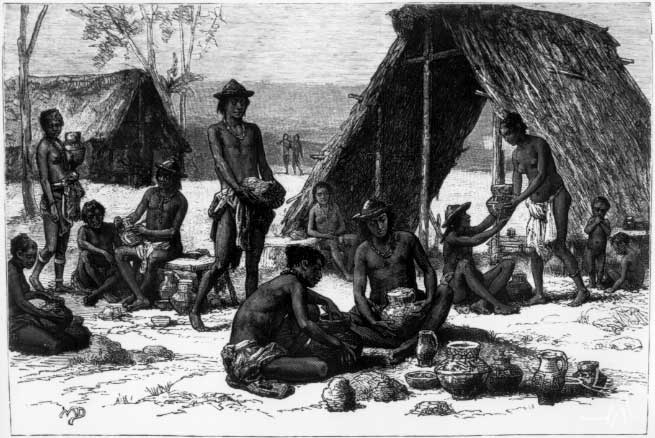

Galibi subsistence basically comes from agriculture. Every Galibi man who has a sense of pride has a fine garden which he takes care of daily with his family. When a Galibi talks about his “things” (“abattis", referring to gardens) he says everything. At times, those who have grandchildren and nephews set aside, as inheritance, a piece of land for them.

In the Galibi village, there are five gardens planted, located a few minutes from the houses of their owners. The Indians plant manioc, yams, sweet cassava, potato, banana, pineapple, corn, tomato and maracujá. There are numerous fruit trees in the areas surrounding each house, of coco, avocado, oranges and tangerine, abiú and many cashew-trees, besides the immense mango trees that are part of the typical landscape of the village.

Hunting and fishing complete the rest of the food diet. Actually, these activities are only undertaken by two men of the village, which limits what the Galibi consume. Since the elderly receive their retirement pension from Funrural, they buy fish from fishermen of the area and chicken in Oiapoque, besides other food products.

Two specialties of the Galibi are worth mentioning. The "galettes" (cakes) of manioc, Indian bread, made of scraped manioc, but never of puba (macerated manioc), manioc cereal mixed in water, which, according to them, leaves the manioc without substance. It is a type of thick beiju. When they are well made, they can be kept in a dry place for a long time. The second item is caxixi, fermented manioc drink, very fine and rosy colored due to a reddish potato used in its preparation. At times, Mr. Lod jokes and offers it as an apéritif or digestif. A soup of smoked fish with yams is another typical dish that is highly prized.

Family organization and marriage

The nuclear family of the Galibi which came from Guiana consisted of two brothers, Julien and Geraldo Lod, married to two sisters, and a sister of the Lods, married to Joseph Jean-Jaque. In French Guiana, Jean-Jaque lived in Grand Village and the Lods in Couachi, two places near each other. The grandfather of the Lods was called Emile François Zacharie and was the cousin of Grand Emile (Alobé Emile), grandfather of the wives of Geraldo and Julien Lod.

The Indians who live in the village of São José are direct descendants of these families. Another family is comprised of a third sister of the wives of the Lods, who is married to a retired (non-Galibi) teacher, with no children. According to Galibi marriage rules, which designate a preference for marriage between classificatory cross cousins, the youths of the first descending generation either remained single or married with non-Indian women, which in fact happened. This situation must not have been very easy for them. But today, the non-Galibi, married in the village, are quite well integrated and liked by the more elderly, their mothers- and fathers-in-law. Traditionally when two young people intended to marry, generally a choice which was already arranged by their parents, they and their families performed a sequence of ritualized acts, such as the betrothed man’s and his father’s visit with the parents of the bride, followed by the offer of a cigar. The young couple were submitted to difficult tests to prove their competence as accomplished agriculturalists, hunters and artisans, for the men, and perfect cotton weavers, cloth-weavers, ceramic artists and preparers of caxixi, for the women.

Rites of passage

Traditionally, basides marriage, the most important rites of passage, for the girls, were the restrictions following first menstruation, when they were informed about the danger inherent to menstrual blood which could unduly attract, by its smell, monstruous aquatic spirits. During these periods, the women cannot go to the river, to the garden, cook, nor even prepare caxixi.

The young men would go through a period of rigorous learning and seclusion when they intended to become shamans. Finally, the end-of-mourning rituals were occasions when many people of different local groups came together, and thus at the same time that they would despatch the spirit of the dead, freeing it to go up to the sky, the Galibi would reconstitute their social and sumbolic world as well as renew the cosmos.

Today, the rites of passage are different, but the ancient beliefs still make sense and their values are preserved. This creates positive ambivalence and ethnicity. Children are baptized and are duly prepared for their first communion. Mr. Geraldo Lod is proud that his marriage, in the 40s, in Mana, was the first to be celebrated as both a civil and religious union, following the Catholic faith. "I opened the way”, he said. The young people, today, still have to go through school, at times go through public competition for jobs, and prepare themselves for a life of work, which consists of traditional subsistence activities, plus tasks that will permit them to earn some money, and political training that ensures for each individual and his group, autonomy and integration into ever more extensive networks.

Sources of information

- ARNAUD, Expedito. Os índios Galibi do rio Oiapoque : tradição e mudança. In: --------. O índio e a expansão nacional. Belém : Cejup, 1989. p. 19-86. Publicado originalmente no Boletim do MPEG, Antropologia, Belém, n.s., n. 30, jan. 1966.

- CASTRO, Esther de; VIDAL, Lux Boelitz. O Museu dos Povos Indígenas do Oiapoque : um lugar de produção, conservação e divulgação da cultura. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 269-86. (Antropologia e Educação)

- DIAS, Laercio Fidelis. Curso de formação, treinamento e oficina para monitores e professores indígenas da reserva do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 360-78. (Antropologia e Educação)

- RENAULT-LESCURE, Odile. Evolution lexicale du galibi langue Caribe de Guyane Française. Paris : Orstom, 1981. 251 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

. As palavras e as coisas do contato : os neologismos Kali’na (Guiana Francesa). In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita (Orgs.). Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp, 2002. p. 85-112.

. Textes Galibi. In: CONTES amérindiens de Guyane. Paris : Conseil International de la Langue Française, 1987. p.8-67.

- TASSINARI, Antonella Maria Imperatriz. Da civilização à tradição : os projetos de escola entre os índios do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.157-95.

- VIDAL, Lux Boelitz. O modelo e a marca, ou o estilo dos “misturados”. Cosmologia, história e estética entre os povos indígenas do Uaçá. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Antropologia, história e educação : a questão indígena e a escola. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p.196-208.

; SILVEIRA, Luís Fábio; LIMA, Renato Gaban. A pesquisa sobre a avifauna da bacia do Uaçá : uma abordagem interdisciplinar. In: SILVA, Aracy Lopes da; FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Orgs.). Práticas. pedagógicas na escola indígena. São Paulo : Global, 2001. p. 287-59. (Antropologia e Educação)