Bororo

- Self-denomination

- Boe

- Where they are How many

- MT 1817 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Bororo

The term Bororo means, in the native tongue, 'village court'. Not by coincidence, the traditional circular distribution of the houses make of the court the village center and the ritual space for this people, which is characterized by a complex social organization and a rich ceremonial life. Although today the Bororo possess a discontinuous, deteriorated territory, the vigor of the their culture and their political autonomy have been weapons against the predatory effects of their contact with 'the white man', which has been ongoing for at least 300 years.

Name

The Bororo call themselves Boe. The term Bororo means 'village court', and is their official denomination today.

Along the years, other names were used to identify this people, such as: Coxiponé, Araripoconé, Araés, Cuiabá, Coroados, Porrudos, Bororos da Campanha (referring to those who lived in the region near Cáceres), Bororos Cabaçais (those from the Guaporé River basin), Eastern Bororos and Western Bororos (an arbitrary division made by the Mato Grosso State government during mining times that used the Cuiabá River as reference point).

Among their self denominations are those associated with territorial occupation: the Bóku Mógorége ('inhabitants of the cerrado', the savannas of Central Brazil) are the Bororo from the villages of Meruri, Sangradouro and Garças; the Itúra Mogorége ('forest inhabitants') correspond to the Bororo of the villages of Jarudori, Pobori and Tadarimana; Orari Mógo Dóge ('inhabitants of the place of the pintado fish') refers to the Bororo of the villages of Córrego Grande and Piebaga; Tóri ókua Mogorége ('inhabitants of the foothills of the São Jerônimo Mountain Range') was the name given to a group that has no village left; Útugo Kúri Dóge ('the ones who use long arrows') or Kado Mogorége ('inhabitants of the bamboo woods') are the Bororo from the village of Perigara, in the Pantanal region.

Location

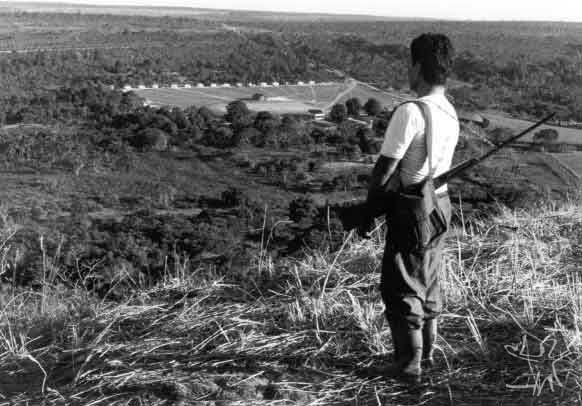

The traditional territory of Bororo occupation reached Bolivia to the West; the Center-South of the State of Goiás to the East; the margins of the rivers that form the Xingu River to the North; and, to the South, the vicinity of the Miranda River (Ribeiro, 1970:77). It is estimated that the Bororo have been living in this area for at least 7,000 years (Wüst & Vierter, 1982).

Language

Boe Wadáru is the term used by the Bororo to designate their original tongue. Linguists Rivet (1924) and Schmidt (1926) classified it as isolated and possibly linked to the Otuké branch. Later a new paradigm simplified the classification of Indian languages, grouping them together according to certain similarities, and the bororo language was placed in the Macro-Jê linguistic branch (Manson,1950; Greenberg,1957).

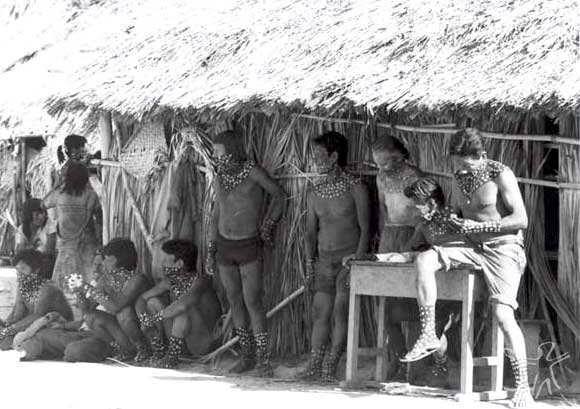

Today the bororo language is spoken by almost the entire Bororo population. But until the end of the 1970s, The Salesian Indigenous Mission subjected children and teenagers to a school system that prohibited the use of the native tongue to be spoken in the villages of Meruri and Sangradouro. A process of re-evaluation and auto-criticism by the Salesian missionaries ended up with the rescue of the original language and in bilingual education. Thus nowadays in all Bororo villages the majority of the population speaks Portuguese and Bororo. In daily life, the language used is Bororo, with neologisms assimilated from regional Portuguese, which is used only in inter-ethnic contacts.

Present land status

Today the Bororo have six demarcated Indigenous Lands in the State of Mato Grosso that form a discontinuous, environmentally deteriorated area 300 times smaller than their traditional territory. The Meruri, Perigara, Sangradouro/Volta Grande e Tadarimana Indigenous Lands are registered and homologued; the Jarudori Indigenous Land was set aside by the SPI, but with time was continuously invaded, to the point that now there is a city on it; the Teresa Cristina Indigenous Land is sub judice because its limits were annulled by a presidential decree.

In the 1970s, the high level of dissatisfaction of the Bororo brought about a movement demanding the recovery of their traditional territories and the improvement of health and education services. An emblematic case of such movement was the struggle for the Meruri area, which peaked with the infamous massacre carried out by landowners from General Carneiro.

At present the movement encompasses all Bororo villages and strives to find solutions for land disputes in the Teresa Cristina, Jarudori and Sangradouro Indigenous Lands; as well as ensuring the inclusion of the Bororo in the EIA/Rimas (reports on environmental impact) of the Paraguai-Paraná and Araguaia-Tocantins waterways; and the diversion of the tracks of the Ferronorte railroad, in the vicinity of the Teresa Cristina Indigenous Land.

History of contact

Available historical sources inform that the initial contact of the Bororo with the national society goes back to the 17th Century, when the 'bandeiras jesuítas' (Jesuit expeditions) came from Belém to the Araguaia River basin and followed the Taquari and São Lourenço rivers towards the Paraguai River. In mid-18th Century contacts intensified with the 'Bandeiras Paulistas' (expeditions from São Paulo) and the discovery of gold in the region of Cuiabá. In this period, gold exploration was responsible for splitting the group into Western and Eastern Bororo (Bororo Ocidentais and Bororo Orientais respectively).

The Western Bororo, also called 'Bororo da Campanha' and 'Bororo Cabaçais', suffered the aggression of the contact with colonists from Cáceres and Vila Bela to a point that, by mid-20th Century, they were considered extinct.

The Eastern Bororo, commonly known as 'Coroados', remained isolated until mid-19th Century, when they became the protagonists of the most violent episodes in the history of the occupation of Mato Grosso. The construction of a road that crossed the São Lourenço River Valley, connecting Mato Grosso to São Paulo and Minas Gerais, began a war that lasted more than 50 years and ended with the total surrender of the Eastern Bororo.

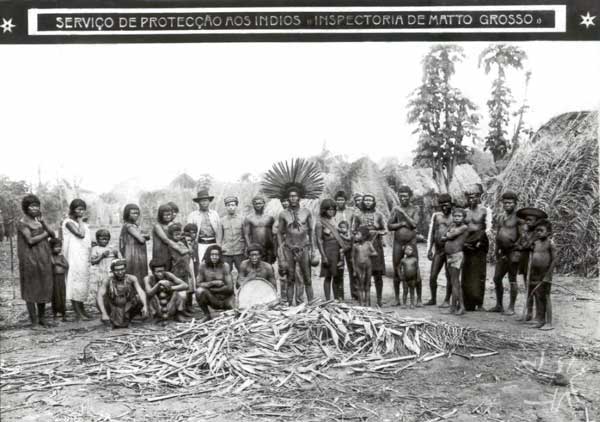

'Pacification' brought the creation of the Teresa Cristina and the Isabel Military Colonies in 1887. Soon after the Republic was declared, in 1896, Marshall Rondon demarcated the Teresa Cristina Colony, with the idea of preserving an important part of the traditional Bororo territory. Until 1930, Rondon reserved for the Bororo other areas of the São Lourenço River Valley, among them the lots called São João do Jarudori, Colônia Isabel and Pobori, which had been under the SPI's responsibility since 1910.

On the Araguaia River basin, strayed Bororo groups - which lived in the regions of the Mortes and Garças rivers and along both margins of the Araguaia River - were affected by the occupation of farmers from Goiás and by diamond 'garimpos' (prospecting areas). During that time violent conflicts took place, and the provincial government charged the Salesians, who had been removed from Teresa Cristina Colony, with the task of pacification. In 1902 they founded the Sagrado Coração Colony and began the catechizing of the Bororo. In 1906 they founded Sangradouro Colony, which later would receive the Xavante expelled from the Parabuburi area.

To summarize, the process of contact with the national society resulted for the Bororo not only in the loss of most of their traditional territory but also a drastic population reduction.

Population

Available historical information indicate that in the last decades of the 19th Century there were some 10,000 Bororo. However, within a few years many of them died in consequence of the negative effects of contact, such as wars, epidemics and famines. The picture was so discouraging that anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro (Os Índios e a Civilização, Petrópolis, Vozes,1970:293), when analyzing the 1932 Census, argued that the high degree of vulnerability of the Bororo was an indication that they were in the last stages of the extinction process. However, from the 1970s on, population growth has been taking place, and the 626 individuals registered by Father Uchoa em 1979 are now 1,024.

Current demographic data register the following distribution of the Bororo population, by area and by river basin:

| Indigenous land | Village | Population |

| TI MERURI | Meruri Garças | 328 61 |

| TI SANGRADOURO (Xavante) | "Morada Bororo" (ocupada pelos Xavante, essa área não é reconhecida como bororo) | 63 |

| BACIA DO RIO ARAGUAIA | ||

| TI JARUDORI | (Área Indígena totalmente ocupada pela cidade Jarudore) | ----- |

| TI TADARIMANA | Tadariamana; Pobori; Paulista; Praião; Jurigue | 173 |

| TI TERESA CRISTINA | Córrego Grande Piebaga | 254 66 |

| TI PERIGARA | Perigara | 79 |

| BACIA DO RIO SÃO LOURENÇO | 572 | |

| POPULAÇÃO TOTAL | 1.024 |

Source : Missão Salesiana, 1997 and Saúde/Funai/ADR Rondonópolis, 1997.

Social organization and kinship

Among the Bororo the political unit is the village (Boe Ewa), formed by a group of houses built on a circle, with the men's house (Baito) at the center. West of the Baito is the ceremonial court, called Bororo, where the society's most important ceremonies are held. Even in the villages where the houses are disposed in a linear way because of the influence of missionaries or of government agents, the village circularity is considered the ideal representation of the social space and of the cosmological universe.

In the complex Bororo social organization individuals are classified according to their clan, their lineage and their residential group. Descent among the bororo is matrilineal; thus the newborn receives a name that will identify him/her to his/her mother's clan. However, although that is the ideal norm of conduct, in practice this may be manipulated in order to satisfy other interests (Novaes, 1986).

In the spatial distribution of the houses around the village circle each clan occupies a specific place. The village is divided into two exogamic halves - Exerae and Tugarége -, each of them subdivided into four main clans, which are composed of several lineages. There is a hierarchy among lineages manifested in categories such as larger/smaller, more important/less important/ older brother/younger brother. People who belong to the same clan but to hierarchically different lineages are not supposed to live in the same house.

In the traditional political structure, three powers can be identified: the Boe eimejera, who is the chief of war, of the village and of the ceremonial; the Bári, who is the shaman of the spirits and of nature; and the Aroe Etawarare, who is the shaman of the souls of the dead. Nowadays there is also the Bae eimejera, who is the chief of whites, that is, the chief who does the interface with the whites.

Here is a classic model of a Bororo village, with the divisions into two exogamous and clan halves, with each clan's great heroes and chiefs (Adaptation: Viertler,1978).

Usually two or three nuclear families live in each village house. Residential groups are uxorilocal, a rule according to which a man who gets married is supposed to move into his wife's house but continues to be a member of his old lineage. For that reason, in one given house there can live people from different social categories, clans and lineages. Marriage among the Bororo is rather unstable and there is a high rate of separations, so a man may live in several houses along his life.

In general, the ties of an individual with his original group are stronger than those with his wife's group, despite the fact that he has a more intense contact with the latter's members and owes them obligations such as hunting and fishing for them, working on his father-in-law's field and making ornaments for his wife's brother. But such activities, claims Novaes, only mark physically his presence in the group. Regarding his original group, however, the man is in charge of taking care of his sisters' future, and it is through them that he projects himself socially. It is to his sisters' children - his iwagedu - and not to his own that a man passes on his names and the ritual rules associated with them. Besides, even though he lives away from home, the man has the responsibility for the cultural heritage of his group of origin and represents it in the ritual activities: chanting, dancing and manufacturing of ornaments, as well as specific ritual services. Regarding his own children, he is in charge of their physical survival, but it is the responsibility of his brother-in-law, his wife's brother, their cultural formation.

In spite of dividing the same roof, the nuclear families that make up a domestic group establish internal divisions among them. The space for each family is located on the house's extremities, never in the center. In their area they keep all their belongings, eat, sleep and receive their visitors.

The center of the house is not exclusive of any of the families and is the place where the visitors considered important are received and where rituals are held. It is the space that represents that social unit (clan or lineage) which certain members of the nuclear families are part of. It is also in the center of the house that the fire is placed for cooking, keeping mosquitoes away or simply heating the air at night (Novaes, 1986).

During the day doors and windows are kept permanently open so as to control what is going on in the village. In the rituals in which women cannot participate doors and windows are closed. The same happens during mourning, because mourners keep themselves away from social life and cannot look at the village center. During the funeral the mourners' house is kept empty, and afterwards it should be destroyed. For those reasons Sylvia Caiuby Novaes recognized in the bororo house a space for the contact between the domestic and the political-juridical realms.

Women spend more time inside the house, the place where their tasks, such as cooking and the manufacture of straw utensils, are performed. In Novaes words, "it is also in the baatada (which encompasses the circle of houses in the village outskirts) that appear the great gossips, activity in which the Bororo women seem to outdo women of any other ethnic group (men are expert gossip as well, but in their mouths gossip seems to acquire a serious tone). The house is also the center of daily sociability, and women are constantly visiting and exchanging favors with each other, even though they live just a short distance away" (1986:100).

Ceremonial life

Rituals are a constant in Bororo life. The most important rites of passage (in which people pass from one social category to another) are naming, initiation and funeral. According to Novaes, "In the naming ritual the child is formally introduced into the Bororo society of his/her iedaga (the person who gives the name is the mother's brother) and of the women of his/her father's clan, who ornament him/her for the ritual.

These persons synthesize in a clear way the attributes that form the personality of the Bororo and that integrates in a consistent way juridical aspects( transmitted by the iedada and associated with matrilinearity) and aspects of a more mystical character (associated with patrilinearity)" (1986:230). With his/her name, the child begins to be associated with a social category - a clan's lineage - linked to a cultural hero of bororo society who, in mythical times, established the fundaments of social life, which has to be continued by concrete human beings.

Funeral is the longest of the bororo rituals and was also described and interpreted by Sylvia Caiuby Novaes:

"It may sound like a paradox, but it is precisely through the funeral that Bororo society reaffirms the vitality of its cultural life. This is a special moment for the socialization of the young, not only because it is at that time that many of them are formally initiated, but also because it is through their participation in the collective chants, dances and hunting and fishing trips that are carried out in such occasions that they have the chance of learning and realizing how rich their culture is. But why making of a time of loss, such as someone's death, a moment of cultural reaffirmation and even of re-creation of life?

For the Bororo, death is the result of the actions of the bope, a supernatural entity involved in every process of creation and transformation, such as birth, puberty and death. When a person dies, his/her soul, which the Bororo call aroe, moves into the body of certain animals, such as the jaguar, the puma or the 'jaguatirica' (spotted leopard-cat). The deceased's body is wrapped in straw mats and buried in a shallow grave dug in the circular village's central court. Each day the grave is watered in order to accelerate the decomposition of the body, whose bones will be, in the end of the process, adorned. Between an individual's death and his/her body's ornamentation, which will then be buried for good, two or three months pass. It is a long time, during which the great rituals are performed. A man will be chosen to represent the deceased. Adorned all over, his body is completely covered with feathers and paintings; on the head he carries an enormous feathery headdress and a visor made of yellow feathers covers his face. In the village court it is no longer a man who dances but rather the aroemaiwu, literally the new soul who, with its movements, presents itself to the world of the living.

Among the several tasks the dead person's representative is supposed to perform, the most important will be hunting a large cat, whose skin shall be given to the deceased relatives, in a ritual in which the entire village participates. This will ensure the vengeance of the dead person, through his/her representative, over the bope, the entity that caused his/her death. Such ritual creates and re-creates Bororo society, revealing the mysteries of a society that makes of death a moment for the reaffirmation of life" (Novaes, 1992).

Besides funeral and naming, the Bororo's intense ritual life includes also the perforation of the ears and of the lower lip, the celebration of the new maize, the preparation of hunting and fishing trips, and the celebration of the jaguar skin, of the gavião real (harpy eagle) and of the jaguar killer, among others. In all those cases, new relations are superimposed upon old ones, resulting in a social configuration in which individuals maintain relations emanating from various instances, with different rights, obligations, approaches and forms of treatment. The emphasis on one type of relationship or another depends on the social situation in which the people involved are (Novaes, 1986).

Present political organization

Bororo villages maintain their autonomy and present political situations that are consequence of the different solutions derived from the process of contact. At Meruri village, the choice of the Boe eimejera, the 'chief', is made through direct voting and do not follow traditional orientations, thus expressing a clear separation between political and ceremonial leadership.

In the other villages, the political organization still follows the traditional form. The relations among the Bororo villages are oriented by the social, political and, especially, religious relationships, in which traditional funeral is an essential factor.

Knowledge of nature

The Bororo recognize a wide range of 'ecological zones and sub-zones' in the environment that surround them, among which the most important are the Bokú ('cerrado', the savannas of Central Brazil), Boe Éna Jaka (transition areas) and Itúra (forest). Each ecological zone is associated to specific plants, soils and animals, representing an integrated system of those elements and Man. Each zone is also divided into smaller subdivisions.

Annual cycle of activities

Two natural phenomena define the Bororo annual cycle of activities. The occurrence or absence of rain divide the year into two seasons: Joru Butu (dry) and Butao Butu (rainy). The absence of the constellation of the Pleiad, Akiri-doge, from the night sky, which lasts about a month, marks the passage between the Akiri-doge Èwure Kowudu (dry season ceremonies) and the Kuiada Paru (rainy season ceremonies).

Economic activities

The bororo economic system is characterized by a combination of the activities of gathering, hunting, fishing and agriculture. The process of contact has introduced new forms of social and economic relations, such as the possibility of finding a job, selling products ('arts and crafts') and retire. In any case, the activities the Bororo develop in their territory are still deeply marked by their knowledge of nature and of its potentialities and limitations.

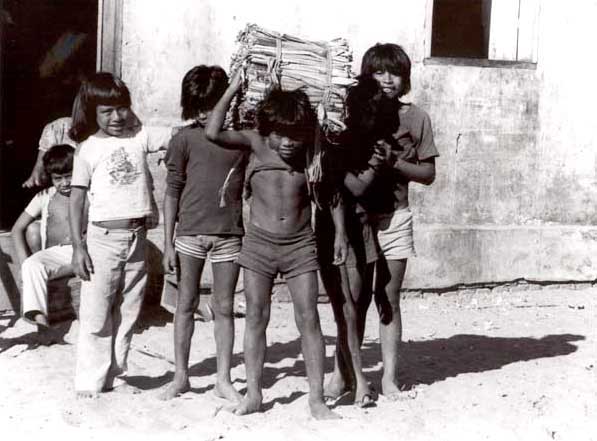

The people who work together in a house also share the 'roça' (planting field). Men do most work in the 'roça': slashing, burning and weeding; women help only in planting and harvesting. Women are in charge of gathering honey, coconuts, fruits of the 'cerrado' and bird and turtle eggs. Children and sometimes husbands take part in such activities (Novaes,1986).

The most visible change brought about by contact was the disappearance of nomadic activities, Maguru, that used to be held during the dry season, when a substantial part of the village moved around in long trips of territorial exploration. Agricultural activity, on the other hand, was intensified, with the introduction of new techniques and new products.

The Bororo are still expert hunters and fishermen, in spite of the increasing scarcity of animals caused by the environmental imbalances brought about by agricultural and livestock activities in the regions where they live. Both fishing and hunting, which are eminently masculine activities, are performed individually or collectively, and still have important places in the diet and in ceremonial foods, as well as in social relations, given the prestige accorded to good hunters/fishermen.

Slash and burn agriculture is practiced by the families in an average area of .5 hectare, which is used for three consecutive years and then left fallow for at least six years. Typical products are maize, rice, cassava, beans, pumpkin etc. Maize cultivation follows the orientations of the chief and certain supernatural sanctions, especially regarding the consumption of new corn, which requires a purification ceremony, Kuiada Paru. Nowadays some communities depend on technological innovations to produce. In the case of Meruri village, for instance, there is a great dependence on tractors for the clearing of the fields and the preparation of the soil.

Cattle raising is an activity still not very developed and not much adopted by the Bororo, but beef is already an important item in the diet, especially in Meruri village.

Relations with the regional society

The Bororo reaction against the loss of their cultural traits, maintained along the process of contact, is remarkable for its specificity and originality. The persistence of the practice of the Bororo funeral is an example of the resistance to assimilation, since while it takes place all 'productive activities' are suspended. In the words of anthropologist Sylvia Caiuby Novaes, "Through those rituals the bororos transgress the order that [the outside world wants to] establish for them and firmly contrapose themselves to 'the harmonious integration to national society'" (1993:132-133).

The autonomy of the Bororo vis a vis regional life is more developed in the social and political than in the economic plan. Relations of 'compadrio' (the special relationship of a child's parents with the child's godparents) are increasingly frequent, as well as marriages with regionals. Such situations have caused conflicts regarding land ownership and the very participation of the 'mestiços' (mixed blooded) in community life.

In what refers to political representation, Bororo strategy is exemplary. Electing a Bororo city councilman and a mayor has given an important role to the people of the Meruri Indigenous Land. Such role is reinforced by the fact that the Bororo are 50% of the city's consumers and, contrary to the Xavante, are regarded as good payers by local merchants.

Health situation

Morbidity rates of the Bororo population are relatively constant and reflect the precariousness of their living conditions. What makes the situation worse are infecto-parasitic diseases, diseases associated with lack of sanitation and habits of hygiene, as well as alcoholism, which is, without question, their main health problem.

The agencies responsible for the health assistance of the Bororo are the Fundação Nacional de Saúde (National Health Foundation), the Funai, the Salesian Mission and the municipal secretaries. In spite of the large number of entities, conditions of health services delivered to them continue to be precarious. This is partly because those institutions do not integrate their work, partly because each of them seems to have its own working methods and partly because they see the problems of health among the Bororo according to their own point of view. Other problems that affect health services are the bad conditions of the infirmaries in the villages, the lack of a human resources policy for Indigenous health, the poor training of professionals and the lack of money for the acquisition of medicines and other necessary products.

Living conditions are just regular, especially in the villages where agents made the Bororo change their huts for brick houses. However, in the villages where houses are built in the traditional style, with straw, the adequacy of housing to Bororo patterns and practices make living conditions better in terms of sanitation and environmental comfort.

Governmental and non-governmental projects in the region

In 1997, the only government project in the region was the Prodeagro (Programa de Desenvolvimento Agro-Ecológico de Mato Grosso/Program of Agricultural-Ecological Development of Mato Grosso), a State initiative with financial support from the World Bank. This project has not developed actions in the region's agricultural and cattle raising activities, but has provided some resources for the sectors of health and education directed to Indigenous communities, such as the Projeto Tucum (Tucum Project), which aims at forming Indigenous teachers.

The actions of non-governmental agencies for the Bororo are developed by the CIMI, the Salesian Mission and by other entities of health assistance, such as Doctors Without Borders and German Dentists, among others.

Note on the sources

For the lay public interested in an overview, the Enciclopédia Bororo, a three-volume work by Albissetti, is the most indicated source; it is considered a sort of 'bible' about this people. For those who are looking for a historical perspective, Os Bororo na História do Centro-Oeste Brasileiro, by Bordignon, is the first organized compilation of the group's history.

The works of Sylvia Caiuby Novaes, Cristopher J. Crocker, Renater Viertler and Thekla Hartmann constitute important references for those who are interested in the social organization and in the ritual aspects of Bororo society. However, the book Vital Souls, by Crocker, has still not been translated into Portuguese.

Sources of information

- ADUGONOREU, Hilário Rondon (Org.). Os animais : Projeto Tucum. Cuiabá : Seduc, 2002. 25 p.

- AGUILERA, Antônio Hilário. Currículo e cultura entre os Bororo de Meruri. Campo Grande : UCDB, 2001. 129 p.

- --------. Mano : currículo e cultura na escola indígena Bororo. Cuiabá : UFMT, 1999. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- ALBISETTI, Cesar; VENTURELLI, Angelo Jayme. Enciclopedia Bororo. v. 1. Campo Grande : Instituto de Pesquisas Etnográficas, 1962. 1076 p. (Vocabulário e Etnografia)

- --------. Enciclopedia Bororo. v. 2. Campo Grande : Instituto de Pesquisas Etnográficas, 1969. 1287 p. (Lendas e Antropônimos)

- BALDUS, Herbert. A posição social da mulher entre os Bororo orientais. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 60-91. (Brasiliana, 101)

- --------. O professor Tiago Marques e o caçador Aipobureu : a reação de um indivíduo Bororo à influência da nossa civilização. In: --------. Ensaios de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Ed. Nacional ; Brasília : INL, 1979. p. 92-107. (Brasiliana, 101)

- BLOEMER, Neusa Maria. Itága : alguns aspectos do funeral Bororo. São Paulo : USP, 1980. 1273 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BORDIGNON, Mário. Os Bororo na história do Centro oeste brasileiro : 1716-1986. Campo Grande : Missão Salesiana de Mato Grosso, 1986.

- --------. Roia e baile : mudança cultural Bororo. Campo Grande : UCDB, 2001. 164 p.

- BRESIL : Arts prehistoriques, la conquete portugaise et l'art baroque, cultures indiennes, de l'esclavage a l'ere industrielle. Paris : SFBD Archeologia, 1992. 77 p. (Dossiers d'Archeologie, 169)

- BROTHERSTON, Gordon. Meaning in a Bororo Jaguar skin. Rev. do Museu de Arqueol. e Etnol., São Paulo : MAE, n. 11, p. 243-60, 2001.

- BULAWSKI, Stefan. Mito-realidade e projeto de um povo. Santa Maria : UFSM, 1979. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CAIUBY Novaes, Sylvia. Aije : a expressão metafórica da sexualidade entre os Bororo. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 37, p. 183-202, 1994.

- --------. As casas na organização social do espaço Bororo. In: -------- (Org.). Habitações indígenas. São Paulo : Nobel ; Edusp, 1983. p. 57-76.

- --------. A épica salvacionista e as artimanhas de resistência : as Missões Salesianas e os Bororo de Mato Grosso. In: WRIGHT, Robin (Org.). Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 343-62.

- --------. Esclaves du démon ou serviteurs de Dieu : Les Bororos et la Mission Salesienne au Brésil. Recherches Am. au Quebec, Montreal : Soc. de Recherches Amer. au Quebec, v. 21, n. 4, p. 37-52, 1991-1992.

- --------. Jogo de espelhos : imagens da representação de si através dos outros. São Paulo : Edusp, 1993. 272 p. Publicado também com o título "Play of Mirrors : the representation of self mirrored in the other, Bororo people of west-central Brazil" pela Univers. of Texas Press, Austin, 1997, 585 p.

- --------. Mulheres, homens e heróis : dinâmica e permanência através do cotidiano da vida Bororo. São Paulo : USP, 1986. 244 p. (Antropologia, 8). Apresentado originalmente como Dissertação de Mestrado. 1986, USP.

- --------. Paisagem Bororo : de terra à território. In: NIEMEYER, Ana Maria de; GODOI, Emília Pietrafesa de (Orgs.). Além dos territórios : para um diálogo entre a etnologia indígena, os estudos rurais e os estudos urbanos. Campinas : Mercado de Letras, 1998. p. 229-50.

- --------. The play of mirrors : the representation of self as mirrored in the other. Austin : Univ. of Texas Press, 1997. 197 p. (Translations from latin America Series)

- --------. Território Bororo : um histórico do processo de expropriação. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1987/88/89/90. São Paulo : Cedi, 1991. p. 504-5. (Aconteceu Especial, 18)

- CAMARGO, Gonçalo Ocho. Meruri na visão de um ancião Bororo : memórias de Frederico Coqueiro. Campo Grande : UCDB, 2001. 579 p.

- CANZIO, Riccardo. Text and music in Bororo chanting. Bulletin de la Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, Genebra : Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, n. 61, p. 63-70, 1997.

- CASTILHO, Maria Augusta de. Os índios Bororo e os salesianos na missão dos Tachos. Campo Grande : Univ. Católica Dom Bosco, 2000. 143 p.

- COLBACCHINI, A.; ALBISETTI, Cesar. Os Bororo orientais : orarimogodogue do Planalto Oriental do Mato Grosso. São Paulo : Nacional, 1942. 454 p. (Brasiliana, Série Grande Formato, 4)

- CROCKER, Jon Christopher. Reciprocidade e hierarquia entre os Borôro Orientais. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 164-85.

- --------. The social organization of the eastern Bororo. Cambridge : Univ. of Harvard, 1969. 360 p. (Ph.D. Dissertation)

- --------. Vital souls : Bororo cosmology, natural symbolism, and shamanism. Tucson : Univ. of Arizona Press, 1985. 393 p.

- CROWELL, Thomas Harris. A grammar of Bororo. Cornell : Cornell University, 1979. 270 p. (Ph. D. Dissertation)

- DAVID, Aivone Carvalho Brandão. Tempo de aroe : simbolismo e narratividade no ritual funerário Bororo. São Paulo : PUC, 1994. 201 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- D'ORTA, Sonia Ferraro. Paríko : etnografia de um artefato plumário. São Paulo : Museu Paulista, 1981. 270 p. (Coleção Museu Paulista: Etnologia, 4)

- --------. Plumária Borôro. In: RIBEIRO, Berta G. (Coord.). Arte índia. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1986. p. 227-38. (Suma Etnológica Brasileira, 3)

- DRUMOND, Carlos. Contribuição do Bororo à toponímia brasílica. São Paulo : IEB, 1965. 134 p. (Apresentado originalmente como Tese de Livre Docência. 1965, FFLCH/USP)

- ENAUREU, Mário Bordignon (Coord.). Mano : um ritual Bororo e uma experiência didático-pedagógica. Cuiabá : Seduc-MT, 1995. 110 p.

- FABIAN, Stephen Michel. Eastern Bororo space-time : structure, process and precise knowledge among a native Brasilian people. Urbana : Univ. of Illinois, 1987. 382 p. (Ph. D. Dissertation)

- --------. Space-time of the Bororo of Brazil. Gainesville : Univ. of Florida Press, 1992. 266 p.

- GRUPIONI, Luís Donisete Benzi. Entre penas e cores : cultura material e identidade Bororo. Cadernos de Campo, São Paulo : USP, v. 2, n. 2, p. 4-24, 1992.

- --------. Levantamento de coleções Bororo em museus brasileiros. Ciências em Museus, Belém : MPEG, v. 1, n. 2, p. 123-36, 1991.

- HARTMANN, Thekla Olga. A Nomenclatura botânica dos Bororos. São Paulo : IEB, 1967. 81 p. (Apresentado originalmente como Dissertação de Mestrado. 1966, USP)

- ISAAC, Paulo Augusto Mário. Educação escolar indígena Boe-Bororo : alternativa e resistência em Tadarimana. Cuiabá : UFMT, 1997. 225 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- KUDUGODU, Pedro Pobo. ^Cegoare boeto piebaga tada. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 5 p. (Livro de Leitura Bororo). Circulação restrita.

- LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude . Saudades do Brasil. São Paulo : Companhia das Letras, 1994. 227 p.

- LOPES, Pedro Alvim Leite. As metamorfoses do corpo : os xamanismos Araweté, Bororo e Tukano a luz do pespectivismo. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ-Museu Nacional, 2001. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- LOWIE, Robert H. The Bororo. In: STEWARD, Julian H. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v.1. New York : Cooper Square Publishers, 1963. p.419-34.

- MAYBURY-LEWIS, D. (ed.). Dialectical societies : the Gê and Bororo of Central Brazil. Cambridge : Harvard University Press, 1979.

- MELEGA, Roberta Pelella. A margem das culturas : um estudo de casos de índios brasileiros marginais. São Paulo : USP, 2001. 213 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MIGUEZ, José Mário Guedes. Chacina do Meruri : a verdade dos fatos. São Paulo : Gazeta Maçonica, s.d. 224 p.

- MUCCILO, Regina Maria. Adugo-Boe E-Mori : alguns aspectos etnográficos da caça da onça entre os Bororo do Mato Grosso. São Paulo : USP, 1983. 186 p. Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MUGUREU, Edmundo Iwodo. Boe emerure. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 6 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- --------. ^Cedure aeroporto ka. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 6 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Irudure Santo Antônio riji. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 10 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Iture avião tabo bakurireuto. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 6 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- MUSSOLINI, Gioconda. Os meios de defesa contra a moléstia e a morte em duas tribos brasileiras : Kaingang de Duque de Caxias e Bororo Oriental. São Paulo : ESP, 1945. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- OLIVEIRA, Sônia Grubits Gonçalves de. Bororo : identidade em construção. Campo Grande : Cecitec, 1994. 131 p.

- QUILES, Manuel Ignácio. Mansidão de fogo : um estudo etnopsicológico do comportamento alcoólico entre os índios Bororo de Meruri, Mato Grosso. Cuiabá : UFMT, 2000. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Mansidão de fogo : aspectos etnopsicológicos do comportamento alcoólico entre os Bororo. In: SEMINÁRIO SOBRE ALCOOLISMO E DST/AIDS ENTRE OS POVOS INDÍGENAS DA MACRORREGIÃO SUL, SUDESTE E MATO GROSSO DO SUL. Anais. Brasília : Ministério da Saúde, 2001. p. 167-88. (Seminários e Congressos, 4)

- RAVAGNANI, Oswaldo Martins. Os primeiros aldeamentos na província de Goiás : Bororó e Kaiapó na estrada do Anhanguera. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 39, n. 1, p. 222-44, 1996.

- RICCIARDI, Mirella. Vanishing Amazon. Londres : Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991. 240 p.

- SERPA, Paulo Marcos N. Boe Epa : O cultivo da roça entre os Bororo do Mato Grosso. São Paulo : USP, 1988. 391p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Os índios Bororo : estudo de impacto ambiental da Ferronorte no estado do Mato Grosso. São Paulo : Tetraplan Consultores, 1995.

- SILVA, Carolina Joana da; SILVA, Joana A. Fernandes. No ritmo das águas do pantanal. São Paulo : USP-Nupaub, 1995. 210 p.

- SILVA, Joana A. Fernandes. O Índio : esse nosso desconhecido. Cuiabá : UFMT, 1993. 149 p.

- TACCA, Fernando Cury de. Rituaes e festas Bororo : a construção da imagem do índio como "selvagem" na Comissão Rondon. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 45, n. 1, p. 187-220, jan./jun. 2002.

- TUAGUEBOU, Benedito. ^Cegireadure toro bakurireuto. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 8 p. (Livro de Leitura Bororo). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Iture mato bakurireuto imagowo - ^Cegimijeraji aroi bogai. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 8 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Quarta-feira meriji - ^Cedure palácio paiaguás ka. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 5 p. (Livro de Leitura Bororo). Circulação restrita.

- --------. Sexta-feira meriji - ^Cedure toro Santo Antônio tori - Cerudure toro ceboje. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 6 p. (Livro de Leitura Bororo). Circulação restrita.

- --------; MUGUREU, Edmundo Iwodo. Awagu buture ceno, caminhão Keje e Iwogure Koge Eari Ka. Cuiabá : SIL, 1995. 8 p. (Livro de Leitura). Circulação restrita.

- VANGELISTA, Chiara. Missões católicas e políticas tribais na frente de expansão : os Bororó entre o século XIX e o século XX. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 39, n. 2, p. 165-97, 1996.

- VIERTLER, Renate Brigitte. Alcoolismo entre os Bororos. In: CANESQUI, Ana Maria (Org.). Ciências sociais e saúde para o ensino medico. São Paulo : Hucitec, 2000. p. 243-61.

- --------. Caminho de Bakororo : alguns aspectos das representações da vida pós-mortem dos índios Bororo do Brasil Central. Imaginário, São Paulo : s.ed., n. 1, p. 137-53, 1993.

- --------. A duras penas : um histórico das relações entre índios Bororo e "civilizados" no Mato Grosso. São Paulo : USP, 1990. 214 p. (Antropologia, 16)

- --------. As aldeias Bororo : alguns aspectos de sua organização social. São Paulo : USP, 1973. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Aroe j'Aro : implicações adaptativas das crenças e práticas funerárias dos Bororo do Brasil Central. São Paulo : USP, 1982 (Tese de Livre-Docência)

- --------. Karl von den Stein e o estudo antropológico dos Bororos. In: COELHO, Vera Penteado (Org.). Karl von den Steinen : um século de antropologia no Xingu. São Paulo : Edusp/Fapesp, 1993. p. 181-221.

- --------. A refeição das almas : uma interpretação etnológica do funeral dos índios Bororo, Mato Grosso. São Paulo : Hucitec/Edusp, 1991. 222 p. (Ciências Sociais, 27)

- WILBERT, Johannes; SIMONEAU, Karin (Eds.). Folk literature of the Bororo indians. Los Angeles : Univ. of California, 1983. 354 p. (Ucla Latin American Studies, 57)

- WUST, Irmhild. Continuities and discontinuities : archeology and ethnoarchaeology in the heart of the Eastern Bororo territory, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Antiquity, Cambridge : s.ed., v. 72, n. 277, p. 663-75, 1998.

- --------. Contribuições arqueológicas etno-arqueológicas e etno-históricas para o estudo dos grupos tribais do Brasil Central : o caso Bororo. Rev. do Museu de Arqueol. e Etnol., São Paulo : USP-MAE, n. 2, p. 13-26, 1992.

- --------. The Eastern Bororo from an archaeological perspective. In: ROOSEVELT, Anna Curtenius (org.). Amazonia indians from prehistoy to the present : anthropological perspectives. Tucson : Univers. of Arizona Press, 1994. p.315-52.

- WUST, I. Etnicidade e tradições ceramistas : algumas reflexões a partir das antigas aldeias Bororo do Mato Grosso. Rev. do Museu de Arqueol. e Etnol. (Série Suplemento), São Paulo : MAE/USP, n. 3, p. 303-17, 1999

- Funeral Bororo. Dir.: Heinz Forthmann; Darcy Ribeiro. Vídeo p/b, VHS, 20 min., 1953. Prod.: SPI.

- Funeral Bororo. Dir.: Maureem Bisiliat. Video Cor, 46 min., 1990. Prod.: Maureen Bisiliat.

- Passado presente. Dir.: Delvair Montagner. Vídeo Cor, HI-8/Betacam, 18 min., 1995. Prod.: CPCE

- A propos de tristes tropiques. Dir.: Jorge Bodansky; Patrick Menget. Vídeo Cor, U-Matic, 50 min., 1991. Prod.: Yves Billon; Les Filmes du Village

- The Bororo world of sound. Coleção Musics and Musicians of the World, Auvidis-Unesco, gravação de Ricardo Canzio, 1989.

VIDEOS